The year Fiona McMonagle turned eighteen, the hit song ‘Hand in my pocket’ listed a lot of contrary traits its scrawny singer comprised:

I'm free but I'm focused, I'm green but I'm wise

I'm hard but I'm friendly, baby

I'm sad but I'm laughing, I'm brave but I'm chickenshit

I'm sick but I'm pretty baby.

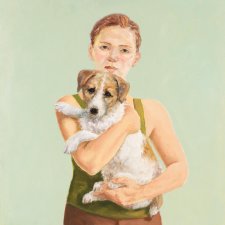

It was the theme of many cultural productions of the 1990s: just because a person – male or female – looks as delicate as a fawn or a fairy, it doesn’t mean they’re not a tough little customer inside; conversely, just because they look like a vicious junkie and act like a banshee, it doesn’t mean they aren’t yearning for love under their brittle exoskeleton.

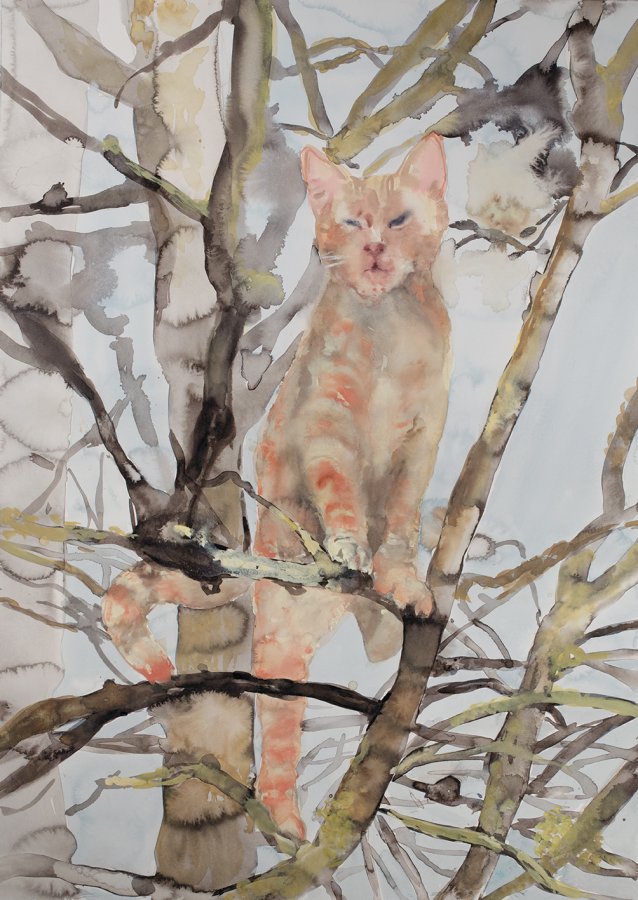

Born in Letterkenny, County Donegal in 1977, Fiona McMonagle grew up amongst a large family in the exburb of Melton, west of Melbourne. With a sister and four brothers, she was a bit of a tomboy. She played netball and did athletics. Unusually, her father, who was a construction worker, was the one who often brought animals home. The family had a succession of dogs and cats; the dogs were shared, but whenever a cat found its way into the house it was understood that it was Fiona’s. Still, she longed to choose a pet herself, and she and her friend used to lurk around a local pet shop. On one occasion – as she tells the story the artist still has a guilty air – they hatched a plan to steal a mouse each. Fiona had already been to a craft store and bought a woven basket to accommodate the wee creature, imagining how cosy it’d be in there. She recalls putting her hand into a tank heaving with mice and letting one scurry up her sleeve. She took it home, where it immediately gnawed through the basket and ran around. Fiona’s mum was terrified, and she got busted. When her friend’s cat had kittens, Fiona wanted one badly but she knew she couldn’t just bring it in the front door; instead, her friend stole around in the night and thrust the feline scrap through Fiona’s bedroom window. Again, Fiona’s mum put her foot down and she had to give it back. Eventually Fiona’s brother Declan brought home a kitten – Stimpy – who was to become the main cat in her life. There was always a racket going on in the household; Stimpy was tense, scratching feistily when she tried to dress him up. Having spent years on edge, the cat grew placid after the young people left home. He and Chop, the family’s main dog, were both white; both died of skin cancer. Fiona can’t see herself being able to get a cat any time soon; but a while ago she gave one to her dad, for his own good.