Though it's the youngest of our national cultural institutions, the idea of an Australian national portrait gallery is over a century old. A number of attempts at establishing collections of Australian portraits were made during the 19th century; and during the first decade of the 20th, the Australian painter, Tom Roberts, encouraged the Commonwealth government to give some thought to the creation of a ‘painted record' of the nation's ‘prominent statesmen'.

While the suggestion ultimately resulted, in late 1911, in the formation of the Historic Memorials Committee – the body that, since that time, has commissioned official portraits of prime ministers, governors-general and chief justices of the High Court – it was not until the final decade of the 20th century that the possibility of a dedicated place for a national, publicly owned portrait collection began to take shape.

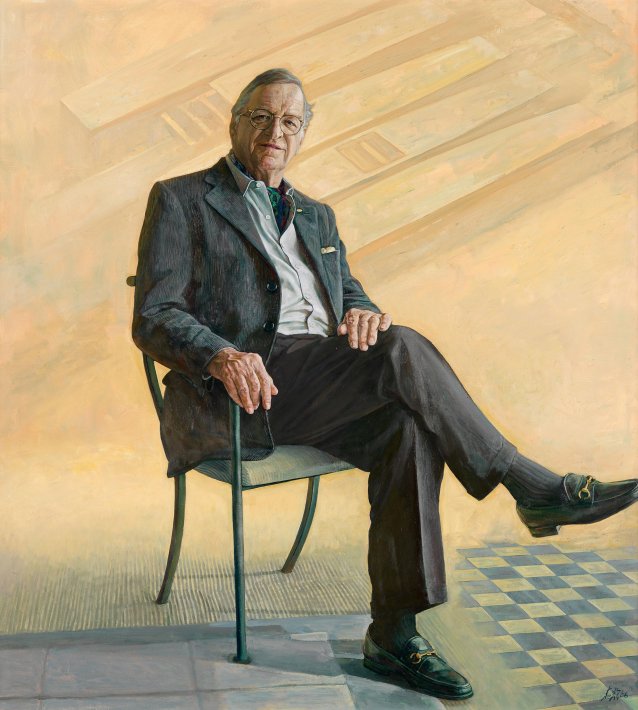

In 1988, with the then almost 80-year-old Archibald Prize having more than proven our interest in images of other people and portraiture's place in Australian art, the Melbourne philanthropists Gordon Darling AC CMG and Marilyn Darling AC decided to make a reality of the idea of an Australian national portrait gallery, visiting the already established examples in London and Washington DC.

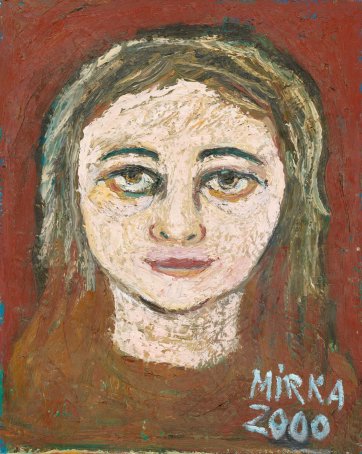

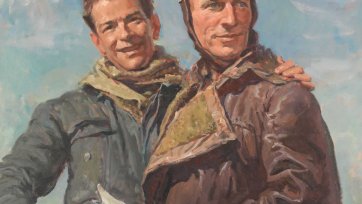

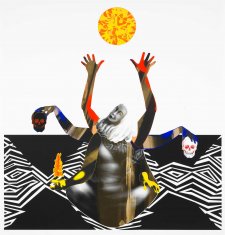

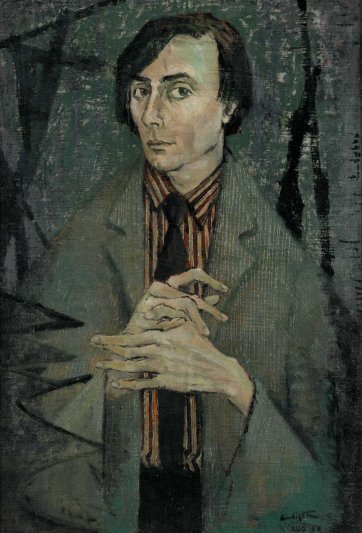

Thereafter, and with the particular encouragement of then National Portrait Gallery Washington Director, Alan Fern, they conceived the vision for an Australian counterpart, consequently seeing to the development of an exhibition that would ‘show people in various parts of the country a sample of what a National Portrait Gallery would do for Australia'. Featuring 116 portraits, in various mediums, of sitters representing spheres such as politics, exploration, the arts, science, business and sport, the exhibition Uncommon Australians: Towards an Australian Portrait Gallery opened at the National Gallery of Victoria in May 1992 and then toured to Canberra, Brisbane, Sydney and Adelaide, introducing visitors not just to the concept of a national portrait gallery but also to the unique interpretive approach such an institution might take: an approach which, through the interplay of art, word and biography, could succeed in creating an enriching and accessible narrative of the country's history, culture and people.

In the wake of Uncommon Australians, the Federal government allocated funds towards the establishment of a portrait gallery, to be located in three rooms in Old Parliament House and managed by the National Library of Australia. This new venture's first exhibition, About face: aspects of Australian portraiture 1770–1993 was launched by Prime Minister Paul Keating in 1994. For the next three years, the Gallery fulfilled its brief to present three or four exhibitions per year drawn from the ‘distributed national collection' of portraits from public and private sources.

In 1997, early on in his term as prime minister and again at the instigation of Gordon and Marilyn Darling, John Howard visited the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC, encountering there an Australian tourist who expressed to him the opinion that there should be ‘one of these at home'. Subsequently, the Howard government announced that the Gallery was to become an institution in its own right, with a budget and a brief to develop a collection of portraits reflecting the breadth and complexity of Australian history and society.

![Trucaninny [Trukanini], wife of Woureddy [Wurati] Trucaninny [Trukanini], wife of Woureddy [Wurati]](/files/c/b/d/0/i10110-th.jpg)