Hello, I'm Dr Emma Kindred, Curator here at the National Portrait Gallery. Welcome to today's virtual highlights tour. I'm joining you from the beautiful sun filled lands of Ngunnawal and Ngambri country, and I would like to pay my deepest respects to Elders past and present and extend that respect to any First Nations community who are joining us today online.

So I'm quite excited to be here in Gallery 2 at the Portrait Gallery in a display titled The Cosmopolitans, and it was about the sort of push and pull between Australia and the cultural centres of Paris and London in the late 90th century and early 20th century. And I've picked out three works, three self-portraits today by women artists that will sort of take us through the journey of women artists practising in those very first decades of the 20th century. And it was quite a shift from the experience of the sort of generations that had preceded them. Though this was a group of women that had access to formal art training and the art schools had a kind of very active membership of women artists. And so this kind of creates a buzz of women exhibiting, being reviewed in the press. And it's a real kind of shift where we have women artists in these kind of first decades being able to pursue art as a career and owning that as a profession. So I'm going to talk about this work here by Evelyn Chapman, another self-portrait by Stella Bowen and one of my favourite portraits from the National Portrait Gallery collection by Nora Heysen.

So this portrait here by Evelyn was is a sort of departure point for my kind of thinking about what I wanted to talk to you about today. I had found this really interesting review when the work was exhibited in 1911 in the Daily Telegraph that said, "Her portrait is worth looking at too for the sake of colour scheme and the painting of the silk wrapper thrown over her shoulder." And what I started thinking about is the role of these garments. What was it about this silk wrapper, about the choice of dress that established Evelyn sort of within the kind of the field or the art world at this time? So she exhibited this work as a student. She had been studying under Dattilo Rubbo in Sydney and she exhibited this under the title of "Une Jeune Fille". So she's almost kind of gesturing to the sort of next steps she'll take in her career when she leaves for Paris, special study at the Académie Julian. So she's almost kind of making a nod to that cosmopolitan experience just in that title. But so when we look at this portrait, we see a woman who is very much kind of wearing the fashion of the time. She has the sort of pouched bodice of Edwardian dress since she did it the waist. Here you have the sort of very high neckline, possibly boned, that has this sort of really lovely delicate detail that connects to this sort of band across the forearm. And she has just laid in with her brush the sort of teal reds and pinks. So this kind of subtle detailing that sort of does connect to this sort of lovely mottled red and brown in the background. Her face is framed by this lovely large black picture hat with these kind of curls of black ostrich feathers, very fashionable at the time, and these fabric flowers. Interestingly, it's very brown and almost the sort of color notes that she selected for her dress connect with the background. So it sort of resides. And what that does is it pushes forward this amazing silk wrapper. And that's what sort of grabbed the attention of the reviewers at the time. And this was a really well received work.

So of the sort of hundred or so pictures that were on display at the Art Society in 1911, this work was illustrated at least two times in the papers, and only sort of two or three would be illustrated. And it did kind of merit mention each time for the wrapper, but also for her really beautiful handling of these hands. And they kind of follow the kind of the fall of the wrapper. And what she's doing here is quite interesting. So she's using hands, which are notoriously tricky to paint. And this kind of amazing articulation of the drape here of this silk fabric to announce her mastery, to say, you know, I'm a competent artist. You know, this is almost sort of like a way of overplaying her hand. If you think about how wearing a silk wrapper, how that fabric might fall, it's not quite as exciting as this. She's giving us drama in the sort of the light undulations and the way sort of shadow falls. There's a lot going on in the way that this fabric kind of sits around her body. And so she's using that as a vehicle to kind of show us her wedge. And she's showing us that she's a very successful artist. And it's interesting when we think of the use of fashion in portrait historically to situate a sitter, whether it's their connections, their status, the circles in which they're moving. And, you know, this is an artist who's very aware of the choices she's making in the selections of those garments. So she has made a choice to use this as a sort of as a vehicle. And she does it very successfully. So Evelyn, like the next two artists that we're going to look at, she heads off to study in Paris at the Academy Julienne and she doesn't return. It's kind of an interesting kind of pattern that's followed by a number of artists where they're sort of seeking to really set out their careers through further study and sort of broader opportunities for exhibition in the Royal Academies and the Paris Salon. And so that's where we kind of, we might lift off over to Stella Bowen. So we've sort of, we've made a bit of a leap here over that 25 years. And we're looking at a work by Stella Bowen that she painted in 1934. We might just do a little bit of a background. She was born in Adelaide and grew up there in a sort of reasonably happy middle-class family. But she had a mother who was not particularly thrilled that she wanted to pursue her career as an artist. And so she really had to kind of fight to, you know, to argue for the importance of art and the way that she could, you know, e-count a career as an artist. Her mother sort of eventually allows her to study at the South Australian School of Art and Craft and then at 17.

She undertakes study with our marvellous Margaret Preston working from live today's week. And Stella talks about this experience as exhilarating. And you can imagine that for a young, aspiring artist that had sort of been denied, you know, this space, this opportunity would have been, you know, a sort of a real shift. And she, like Evelyn was, was looking abroad. And in 1914, well, her mother passes away as well, she heads off to London. And she studies at the Westminster School under Walter Sickert, who has an incredible influence on her approach to composition and colour. And she finds herself in these incredible circles of poets and writers. It's Rapun, T.S. Eliot, Yates. And in 1917, she meets Ford Maddox Ford, who's married at the time, but she falls desperately in love with him. And he becomes sort of a focus for that sort of next decade. She has a child, Julia, in 1920, and really just gives up painting at that time with mother hoid and service to Ford's career sort of becoming the sort of focus and priority. But it's dormant in a way. In 1924, she travels with Ezra and D'Oipi Pound to Italy. And there's this really sort of important moment where she sort of comes face to face with the Italian primitives, Giotto, Friangelo Co., Simone Martini. And while she's not sort of actively working as a painter, these kind of compositional elements, the palette of Giotto, this really kind of thin application of pigment has quite a long lasting effect. And we can kind of sort of, once we sort of sit in the thirties when she's painting again, we can look back to this moment and the way that it, you know, how influential that trip was to her. Five years later, she and Ford Maddox Ford separate. And, you know, the sort of weight of that relationship and the way that it really sort of thwarted her artistic energies can be seen in sort of what happens next. So she's kind of put in the position where she actually needs to rely on her work as an artist to make a living, to support herself, to support her daughter.

And, you know, in the years that follow, we can see sort of her building that sort of assurance and independence and kind of finding her own voice in her painting again. But we have the kind of tricky economic situation heightened by the Great Depression. So in 1932, at the suggestion of her friends, she heads off to the US and it's there that she, you know, undertakes a number of corporate commissions. So she's sort of working on these particular sort of mode of representation and she practises on friends, children to kind of hone a new technique where she is painting on cardboard and it's a really kind of swift application. So she's wanting to work in a way that allows her to produce these commissions in two to three days. So it is swift, dry application of paint worked back. And this portrait is a really good example of her sort of working into that sort of new method. So by this point around 1934, she's had to return to England and she sort of works for the sort of next period as a painter, as a teacher, as a critic. But this portrait here was painted when she's 41, my age now, but she looks very youthful. There's this kind of gorgeous softness in the face and the way that she's modelled her features, which is quite different to say a portrait that sits in the Art Gallery in South Australia that is really quite severe with this very strong shadow cast on the face. And it's kind of interesting to see the way that Stella's modelling of the face changes and shifts in the coming years. And you know, it's almost, you know, for the way I kind of read this portrait, this kind of technique allows that softening. So you can see a very kind of dry brushwork. And she is, she's almost relying on this, and you can sort of see it through the hair probably the most clearly, but she's actually pulling back the paint. So she's using maybe the end of a brush or a sort of a, a very kind of sharp implement to kind of scratch back. So she's creating these layers of texture. And it's, it gives this lovely spontaneity because it doesn't feel overworked. You know, you can sort of see each line constantly worked in as she kind of models, you know, that these lovely sort of curls of her, of that sort of updo.

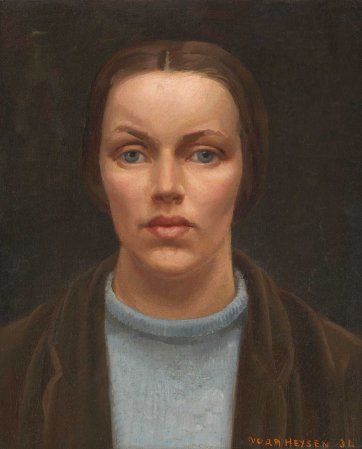

Even the way she kind of articulates just these little lines around the eyes. So delicately handled. And you do really love these, you know, the decorative swathes of fabric, maybe curtains, likely in the studio space that she was working in England. And how, how kind of they're set in against this just hint of a green blouse. And you can see just the sort of lightest under drawing here. And then with a very dry brush, she's sort of worked in sketchily, just the outline of the form of the blouse, its color and these, you know, two, two ties that sort of just fall in casually. And sort of against the sort of detail and working here, it's almost this, this lightness, it's almost like it's sort of floating the form and not working it in, tells us something as well about why she was painting this work. You know, self portraits are often a way for artists, I mean, it's an easy model. So she's selects herself as the subject in a way that she can sort of explore this technique. And she paints another portrait in a very similar way of her daughter Julia, that's in the National Gallery of Australia collection. And you can really see her kind of playing with the application. And, you know, it's interesting to sort of see the freedom that that allows her. It's not a serious exhibition work in the way that say the Art Gallery of South Australia portrait use. So we might move on now to another Adelaide artist painting at the same time. Laura Parson. So this portrait is, for me, one of the most engaging portraits in our collection. And one that catches me every time I walk past it. There's something in the way that that gaze anchors you. And, you know, it's interesting when you think about the way she paints, you know, it's the same time as that portrait by Stella Bowen. But she's a younger artist. She has only just made it to London. Nora Hython is one of Australia's most distinguished portrait painters. She was the first Australian woman artist to win the Archibald Prize and the first Australian artist to become an official war artist during Second World War. And you can see in the way that she models the face. There is clarity in that expression. So we have an artist who is very competent in the way that she paints a portrait. And Nora is an artist who returns to self-portrait her throughout her career. We see her painting in her very early years self-portraits in her father's studio right through to when she's 70 and she's painting herself in an art of smock. So it's interesting for us looking at that span because we are very familiar with Nora's face and the way she handles the painting of her face. But also in the racism that I've done, across what she's wearing in the 30s, this kind of habit of representation in a way, the way that she is clothing herself and using articles of clothing specifically again and again. So it's a sort of play in dressing up that tells us something about how the artist wanted to be perceived. So Nora Heysen was one of eight children, the daughter of Sir Hans Heysen and his wife Selma who herself was quite a competent artist.

So it was a very kind of rich artistic space that she was growing up in. And she began her studies very early and at 15 she was enrolled at the School of Fine Arts and Adelaide and while still a student was exhibiting at the... I might do that again. Sorry, yeah. Go ahead and I'll just... Yeah. Poor Nora, darling. Okay. Nora was one of eight children of Hans Heysen and his wife Selma who herself was a very capable artist. So she was growing up in this very sort of rich artistic cultural space. She began painting and drawing very early and by 15 she was enrolled in the School of Fine Arts and Adelaide. And as a student she is putting works in for display at the Society of Artists in Sydney and by 1931 she has had works acquired by the Art Gallery in South Wales, the Queensland Art Gallery and the Art Gallery South Australia which was incredible for an artist of this... a woman artist of this period. And I think what is really lovely about this work is it tells us something about that success. Now with the earnings from the sale of her works she bought a brown jacket, a brown velvet jacket that she took with her to London. She had gone to Europe with her parents in 1934 and she stayed in London to study at the Central School. And in March 1935, so a few months into that time where she's living by herself and studying, she writes to her father, they had this sort of wonderful dialogue over years, writing back and forth very frequently. She writes of a long days painting. It is self-portrait that I'm painting just the head and shoulders full on. I think it is a better likeness than I usually aspire to and it is a better painting. So we have this close-up front on perspective and it's really minimal dark background. And it's quite a contrast to many of the other self-portraits where we see her sort of side on, holding a palette and kind of addressing us in a very different way. This is quite stark and quite direct. And the way that just her face is the focus, it's extremely arresting. But I love the way that she paints so gently the sort of soft fall of this velvet jacket. And you can sort of see it as it kind of comes over the shoulder and, you know, the sort of rounded fullness of the collar. And that sort of sits over this really beautifully set in blue jumper, which has kind of fine line detailing of the sort of ribbing of this collar. And these knits appear quite a few times in her portraits throughout the 30s. And there's a cream knit in particular that she writes about sort of 60 years later when she's recalling sort of the way she felt about these portraits, what she was wearing, the experience at the time.

And she wrote, "I rather like that portrait because it was all sort of handmade. I knitted the sweater and I made the skirt." So it's sort of my hunch with this work that the blue knit is also handmade by Nora. And, you know, this is an artist living in London, sort of, you know, making dude in a way. But it shows just in what she's wearing here, very simply, you know, an artist who sort of announces her independence, her identity and her ambition as a young artist, wearing a velvet jacket that she had bought with her own earnings and a jumper she had hand knitted. So she's confident she's taking up this space. And I think that's what comes across in this work is that way that she, you know, while she's not wearing an artist's mock, the way she does an other portrait, she is announcing herself as an artist. So, you know, as we reflect on Evelyn Chapman, Stella Bowen and gorgeous Nora Heysen, you know, it's really interesting to see how the way a garment is worn and the reason a garment is worn and how that kind of gives out this lovely insight into the artist themselves, the artist as individual. And, you know, there's this active agency in the selection of these garments when an artist is producing a self-portrait. It's a very conscious decision about the way that they will, you know, don these clothes for themselves. You know, and it's this kind of very articulation of the fabric and the sort of feel of cloth, you know, on the body that becomes, I mean, especially for Evelyn Chapman, it's like this assertion of mastery, you know, I can paint. You know, and it's, it is these deliberate decisions by these artists that I love. And I'm so glad to share with you today that the way that these three artists have been able to produce such enduring, engaging works that tell us something about the way that they navigated a very kind of male dominated environment as artists, as profession, you know, professional artists working at that time in this very particular time and space in the first decades of the 19th century. Thank you for your time. Join us next Tuesday for another virtual highlights tour.