- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

Violet Teague (1872–1951) was among Edwardian Australia's most fashionable and assured portraitists, although the art historical establishment was slow to acknowledge it.

2 portraits in the collection

Gift of the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service 2020

Joanna Gilmour profiles Violet Teague, whose sophisticated works hid her originality and non-conformity in plain sight.

Purchased with the assistance of funds provided by Jillian Broadbent AC 2021

Spanning the 1880s to the 1930s, this collection display celebrates the innovations in art – and life – introduced by the generation of Australians who travelled to London and Paris for experience and inspiration in the decades either side of 1900.

Spanning the 1880s to the 1930s, this collection display celebrates the innovations in art – and life – introduced by the generation of Australians who travelled to London and Paris for experience and inspiration in the decades either side of 1900.

Rebecca Ray on Robert Fielding’s Mayatjara series, Jennifer Higgie on Alice Neel, Elspeth Pitt chats with Yvette Coppersmith, Vincent Fantauzzo on virtual sittings with Hugh Jackman and more.

Jennifer Higgie uncovers the intriguing stories behind portraits of women by women in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection.

Rubina (Ilkalita) Namatjira (1903–1974) was a Kukatja woman and the wife of famous Western Arrernte artist Albert Namatjira.

1 portrait in the collection

Robyn Sweaney's quiet Violet obsession.

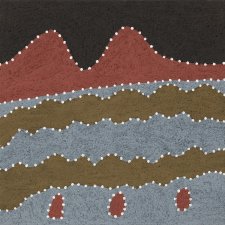

The third row of paintings come from Ngarranggarni (Dreaming).

Born: 1947, Gilbun – Mabel Downs Station, WA

Works: Warmun, WA

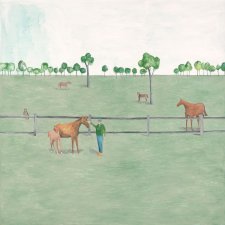

From 1967 until 1981 Matthew Perceval lived and painted in France and during those years produced a large body of portrait paintings.

The fourth row of paintings interweave Ngarranggarni, memories, relationships and Country.

This exhibition features new works from ten women artists reinterpreting and reimagining elements of Australian history, enriching the contemporary narrative around Australia’s history and biography, reflecting the tradition of storytelling in our country.

The second row of paintings recall stories relating to specific sites, experiences and activities.

Stephanie Alexander AO (b. 1940), cook, restaurateur, food writer and philanthropist, has been a major influence on Australian food and culinary culture for 50 years.

1 portrait in the collection

Emily Casey takes in Shirley Purdie’s remarkable self-portrait, Ngalim-Ngalimbooroo Ngagenybe.

The Darling Portrait Prize is a biennial national prize for Australian portrait painting honouring the legacy of Mr L Gordon Darling AC CMG.

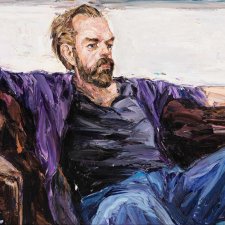

Nicholas Harding: 28 portraits features paintings of Robert Drewe, John Bell and Hugo Weaving alongside gorgeously coloured recent oil portraits, delicate gouaches and bold ink and charcoal drawings.

Andrew Sayers feels the warmth in the paintings Matthew Perceval made while the sun shone in southern France.

The first row of paintings depict stories relating to kinship, introducing significant women relatives.

Archie 100 curator (and detective) Natalie Wilson’s nationwide search for Archibald portraits unearthed the fascinating stories behind some long-lost treasures.

Sarah Engledow likes the manifold mediums of Nicholas Harding’s portraiture.

With a mum who was married to a tradie, you’d think it a fair chance that the baby Jesus would have grown up with a dog in the house.

Andrew Sayers discusses the real cost of George Lambert's Self portrait with gladioli 1922.

Most well-regarded pictures of chickens show them dead. A reliable way to tell if a chicken in a painting is dead is to check if it’s hanging upside down, because unlike, say, cockatoos, chickens don’t practise inversion for enjoyment in life.

Sarah Engledow trains her exacting lens on the nine photographs from 20/20.

Over the years the young Nicholas Harding got his hands on various mice and guinea pigs, but they served mainly to illustrate the concept of mortality.

Sarah Engledow looks at three decades of Nicholas Harding's portraiture.

Dr Sarah Engledow puts four gifts to the National Portrait Gallery’s Collection in context.

Where do we draw a line between the personal and the historical? Although she died in Melbourne in 1975, when I was not quite eleven years old, I have the vividest memories of my maternal grandmother Helen Borthwick.

One half of the team that was Eltham Films left scarcely a trace in the written historical record, but survives in a vivid portrait.

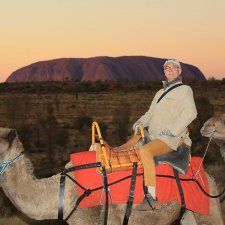

Angus' initial perception of Uluru shifts, as he comes to see it as central to the entire order of Anangu life.