A girl in a city street, waving a chic satchel bag. A man amongst leaves. A full-lipped man in black. A man with impossible eyes. Four different people in four disparate portraits; made for distinct purposes; at various times; and in several mediums. Portraits of, by, and from one donor: Janice McIllree, née Wakely.

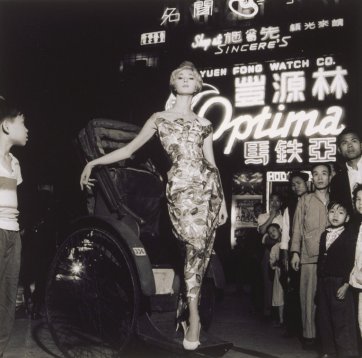

A girl from Crookwell, New South Wales, Janice Wakely graduated from Sydney’s Mannequin Academy in 1952 and began modelling in Melbourne two years later, when she was 24. Regarded as a little too thin by various Australian agencies, she worked on the Commonwealth Department of Trade-sponsored fashion tour to New Zealand in 1956 before leaving for London. Within ten days, she bagged a shoot with Marie Claire in Paris and St Tropez. In no time she was dubbed ‘The Girl of the Moment’ with ‘The Look of 1958’. The Australian Women’s Weekly reported that in England her ‘fragile but tough and oh, so carefully casual’ look had set her apart – for the time being – from ‘the thousands from Commonwealth countries who invade Britain each year to see something of the world before they settle down to marriage and the building of a home and family.’

Although she returned to Australia later that year, it was to be some time before Janice settled down. Returning to Australia in 1958, Wakely laid ‘hands which look delicate – but not helpless!’ on the camera herself. Over the coming years, while modelling on location, she was in a position to capture photographers including Helmut Newton, Athol Shmith and Henry Talbot while they worked with other models. The resulting body of images, held in Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum with diaries and appointment books accumulated over Wakely’s career, testifies to the straightforward process of fashion marketing fifty years ago. Fashion shoots were no-nonsense, unplugged, hilariously low-budget by today’s standards; yet somehow the resulting images remain starkly elegant, and the self-styled models, be they icy or playful, irresistibly alluring. The ‘model who never smiled’ was photographed by Terence Donovan in London in 1960 (even when photographed with her own beloved baby in 1972, Wakely maintained her superb expression of disdain). Over the next two years she starred in the All-Australian Fashion Parades, was featured on the cover of the Women’s Weekly, was Model of the Year and wore the Gown of the Year. In 1963, however, she stepped down from the catwalk and set up the Penthouse modelling agency in Flinders Lane, Melbourne with co-model Helen Homewood.

Following an overseas tour in 1965 she returned to Melbourne and established a studio with fashion photographer Bruno Benini, who, said People magazine, had ‘given many other girls a helping hand up the ladder to success’. It was in about 1968 – when Wakely declared that ‘the Australian sense of fashion is appalling’ – that Tony Adam found his way into her Melbourne studio. Adam, a grazier, grew up in Melbourne and attended Melbourne Grammar school, but left when he was sixteen. At agricultural college he began horseriding and smoking; failing his exams, he went to work in outback New South Wales and Queensland. When he was nineteen, his father bought a Victorian property and put him in charge of it; it was disheartening country. Having spent 1964 and 1965 mustering and branding in the Northern Territory, he gained his first modelling job through a Melbourne friend who worked in marketing for a wool concern. Adam felt ‘like a poofter’ leaning on the bonnet of his mother’s red Falcon in a cardigan made from Cleckheaton yarn. Yet on the strength of the image (for a knitting-pattern book) he was taken up by Latrobe Studios. In the late 1960s he shot his first testosteronecharged film advertisement, for the Holden Monaro two-door coupe. In the darkness of the GMH testing track, filmed by a cameraman in the lidless boot of a car about four feet ahead, he steered pell-mell into blinding lights with fire hoses blatting ‘rain’ onto the windscreen and a terrified Wendy Hughes, in the role of trophy girlfriend, petrified in the passenger’s seat. Meanwhile, back at the ranch, the phone kept ringing, and he continued to be amazed at the amount of money he could earn in a day in the city. Soon, he settled into a routine of working on his farm, and cramming in modelling jobs when he came to market in Melbourne, changing out of his own country attire into, say, a pilot’s uniform, a hard hat and shorts or a business suit over the course of a day’s work.

Not long after the cardigan shoot, when he was about 28, smoking-hot Adam had been approached by the marketing firm USP Benson about appearing in press photographs for Marlboro cigarettes. Some of the earliest images for the brand were taken on his own property, on land he had cleared of ti-tree swamp himself. He made his first filmed Marlboro advertisement in the Grampians; having inched a four-wheel drive down a precipitous track, he and his three fellow models ‘got out … lit up a fag and gazed wistfully into the distant scenery, joyfully puffing on the weed.’ Several of his later Marlboro commercials were directed by Fred Schepisi and he was to be photographed often – with co-stars including red setters and cattle – by John Gollings at the break of day. ‘After two or three hundred shots were taken and nearly as many cigarettes half-smoked and tossed away, a man had an awful feeling and taste in his mouth on those particular mornings’, he writes.

In the early days of his work for Marlboro, Adam played the lady’s man. On one gruelling shoot, undertaken at lunchtime in the Melbourne CBD, he was tasked with running excitedly up a flight of steps in Collins Street to kiss the mannequin Elizabeth Scarborough. Meeting her half-way, he sought her lips with his own, only to find himself mumbling around the base of her swanlike neck. He was instructed to try again, delaying the embrace until he was on the same step as the model. ‘ 5’11” of Elizabeth came flowing down the stairs … 5’ 8 3/8” of me went scrambling up the stairs … but the result wasn’t much better’, he writes. The crowd was getting bigger … I felt like a dork … Wags in the crowd heckled … “put him on a bucket”’. After adjustments to lighting and camera angle, Scarborough was directed to mount the stairs while Adam came down. After a few better takes in which Adam was yet found to be ‘too rigid’, the pair kissed successfully with Scarborough on the step below her screen lover. Janice McIllree remembers ruefully that though he was ‘gorgeous’, she could never find a place for Adam in the shadow of her mannequins on a fashion shoot. It was years before Adam was to exploit the skills he had picked up at agricultural college to the full, smoking and riding simultaneously. There were several other Marlboro men, including Ivan East, a pilot, and Peter Cummings, a former Navy officer; they got the first riding jobs, while Adam was left to sit and watch them ‘hang on’.

From 1976, however, the situation improved and he found himself riding horses and sucking on ‘fags’ for billboards, point-of-sale material and TV. Although he always regarded modelling as a sideline to his real life, he enjoyed the luxury of travelling and was amazed to be allowed to keep outfits worth as much as $400 – one comprising RM Williams boots, suede jacket and moleskin trousers – which were the clothes he liked to wear anyway. In this period he was disconcerted to find an image of his face, in his Marlboro persona, printed at bust-level on a Kayser nightie which was soon snapped up by the wives and nieces of his friends. Having consulted a lawyer about what he called the ‘Head in the Tits Affair’, he signed his first formal contract with Philip Morris in 1977. However, after just a couple of years, the Australian Government restricted cigarette advertising to depiction of the product only, putting an end to the cigarette endorsement of figures such as Paul Hogan, Stewart Wagstaff and Tony Barber as well as the use of Adam’s famous face. He continued to model intermittently into the 1980s. Unlike the American Marlboro men, he has survived, and still lives in rural Victoria. His autobiography, Riding High, replete with stories of his career involving glamorous women, libidinous horses and thousands of halfsmoked cigarettes, was published in the 1990s.

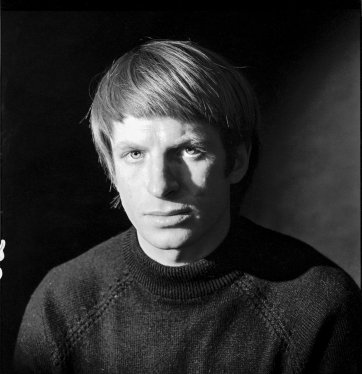

In 1964, Janice Wakely had the temerity to photograph a testy Rudolf Nureyev, as he rehearsed for Le Corsair in Melbourne. She got one shot before he saw her in the wings; as he pouted, and shooed her away, she fired off another. Two years later she photographed a much more cooperative Alan Alder, an Australian dance star who had appeared in The Lady and the Fool and Raymonda at the sixth Adelaide Festival some months before. Alder, born in Canberra in 1937, began his career studying tap and Scottish highland dancing in his home town. Winning a scholarship to the Royal Ballet School in 1957, he studied for a short time before working for a year with the Covent Garden Opera Ballet and proceeding to the Sadler's Wells Royal Ballet. Promoted to soloist, he toured with the company throughout Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Africa over the next four years, starring in productions including La fille mal gardée, which was to become a signature piece for him in the years to come. In 1963 he repatriated, joining the Australian Ballet as a senior soloist. In winter of 1965 he appeared in Robert Helpmann’s triple-bill Melbourne Cup/Yugen/The Display for the opening of the Canberra Theatre. A brilliant character actor, he was promoted to principal artist in 1969.

In 1970 Rudolf Nureyev was in Australia again, dancing Don Quixote with Lucette Aldous, newly-returned to Australia from success in England. With the appointment of Robert Helpmann as Director of the Adelaide Festival that year, Australia was ballet-mad; and in 1971 the engagement of the fairylike Aldous (at just over 41 kilos, and 152 cm, dubbed ‘the pocket Fonteyn’) to her fellow ballet star Alan Alder was widely reported. In the Australian, the charismatic pair was pictured in matching full-length Mongolianstyle embroidered coats trimmed with shaggy wool, while for the Women’s Weekly Alder wore a black jerkin over a violet skivvy with bishop sleeves, Aldous a fulllength dress of crocheted squares accessorized with oversized jewellery. When they married in St Andrews, Canberra in winter 1972 the bride wore a chocolate velvet, mediaeval-style gown with a fur-trimmed cowl hood and long bell sleeves and the groom wore a frock-coat and pants of the same material; they were photographed in their funkadelic outfits for the Women’s Weekly. Two years later, when Alder returned to Canberra, he was pictured at his parents’ house, brooding sideways in an armchair and looking ‘every bit the principal dancer’ in a purple velvet Cossack-style shirt, thick-knit black woollen tights tucked into knee-length boots and an uncompromising Prince Valiant hairstyle. Asked about the Australian Ballet tour of Russia in 1973, he described it as ‘hideous, the food was ghastly and our accommodation and travel arrangements were dreadful’. In 1973 both Aldous and Alder appeared in the renowned Nureyev-Helpmann film of Don Quixote, made in a stuffy hangar at Essendon Airport. In the mid-1970s they returned on invitation to the USSR to study teaching methods in St Petersburg, and after some years’ further performing, in 1983 Alder was appointed to head the dance department at the Western Australia Academy of Performing Arts, Edith Cowan University. The pair have taught ever since, and are designated Western Australian Living Treasures.

Janice Wakely settled down in 1970, marrying Eric McIllree, the founder, chairman and managing director of Avis Rent-A-Car in Australia. Born in 1914, McIllree honed his business skills as a schoolboy at Shore, where he dealt in budgerigars, but his chief interests from boyhood were cars and planes. In his early twenties, having worked as a car salesman, he opened a used-car business. By 1940 Sydney Cash Car Buyers at 160 Castlereagh Street was advertised as the ‘Largest Used-Car Selling Organisation in Australia’. With its profits, McIllree established a car rental firm, at that stage unheard-of in this country. The Second World War put an end to the venture, but by war’s end McIllree had moved along Castlereagh Street to establish McIllree Motors (Air Charter). While working as a pilot himself, on 19 December 1948 he was shot down by the Viet Minh near Saigon, but the only casualty was a pair of suede shoes he had bought in Hong Kong the day before.

On 19 December the following year, he crashed again, this time ‘in the shadow of the Taj Mahal’. Henceforth, he avoided flying on that date. In the postwar years he purchased 55 lumbering Avro Anson bombers, which he flew to England to sell. It was at the wheel of an Anson that he once pranked his sitting and standing passengers by beginning to make an arc as if to loop-the loop: ‘We were all thrown … through the window the blue sky was replacing the earth. Eric levelled the plane out and then came back into the cabin to say “No. These things WON’T loop the loop.”’ Other RAAF disposals aircraft he bought, including every available Supermarine Walrus, were pressed into service with his short-lived venture Amphibious Airways, carrying Indigenous labourers between plantations in New Guinea and New Britain.

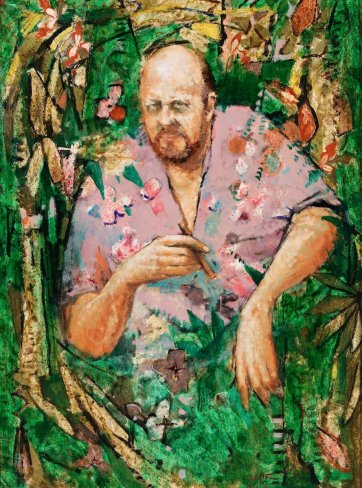

In the early 1950s, again bent on establishing airport car rental facilities, McIllree approached the Department of Civil Aviation and gained the required approval of Trans-Australia Airlines, Ansett and Australian National Airways for the establishment of Airport Car Rentals. The first airport car rental company was established by Warren Avis in the USA in 1946; by 1953, there were franchises in Canada and America. With an eye to the international traveller familiar with the Avis brand, and finding that neither Avis nor Hertz had registered their names in Australia, McIllree laid claim to the names himself, only afterwards negotiating a deal with Avis to the ongoing rights to the name in Australia and New Guinea in perpetuity. Famously, these rights were secured with $10 – ‘all I had’, as he claimed. At least until 1967, Avis held the sole rental concession at Australian airports, and by 1971 McIllree had rented out his millionth car. In late 1973 he told the Daily Mirror that ‘until two June thirtieths ago, the paid up capital of my company was $10 – I wanted to keep it that way until my gross earnings exceeded $10 million’. In 1973, during his terminal illness, it was reported that ‘Eric controls a bedside stock exchange, manning three telephones and a portable dictating machine … sending orders, memos, ideas and requests’ from his harbourside family home, Shellbank in Cremorne, to Avis headquarters in St Leonards. Clifton Pugh painted McIllree on Dunk Island, which the tycoon had bought in 1964 with four associates, who soon retreated. Although he did oversee the construction of limited tourist facilities in his ‘personal fiefdom’, as one employee describes it, he essentially maintained it as a personal retreat, entertaining friends such as Harold Holt, Sean Connery and Ron and Valerie Taylor there. Sometimes claimed, erroneously, to have died in an explosion on one of his own boats in on Sydney Harbour, McIllree divided his time between Shellbank and Dunk.

In 1972 McIllree was diagnosed with carcinoma of the bronchus – in essence, lung cancer. With little time left, he initiated his ‘project for dying’, liaising with his lawyers and auditors, tidying up his 24 companies, and making a VHS documentary, It wasn’t going to happen to me, in which he and Janice spoke of the stages and strategies by which they had come to terms with the ultimate reversal in their dream lifestyle. Pictured with his lovely wife and their baby daughter, Justine, in a series of newspaper articles McIllree spoke of ‘taking a battering’ at the cobaltray clinic, his cyclophosphamide injections and his epiphanies. Gratified by public response to his bravery, he outlived his prognosis and saw in 1973, but succumbed in due course with Janice beside him. Always the promoter, not long before he died he quipped ‘Hundreds of millions of people have died and none of them has come back to say it isn’t any good.’