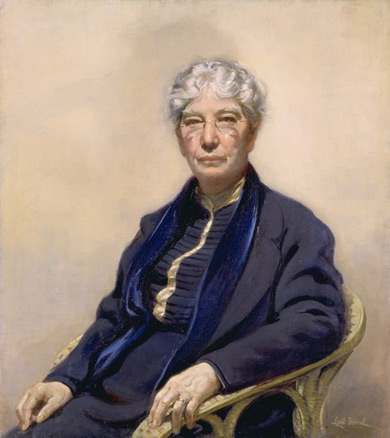

Mary Gilmore

In the early 20th century, artists focussed on capturing a subject’s character through pose and expression. In his portrait of Gilmore, you see Trindall has removed all detail from the background in order to concentrate attention on the individual.

If you could add your own background to the portrait, what would it be?

Gilmore is posed at an angle but turns her head to look directly at the viewer. Her gaze is wise and reflective.

What words would you use to describe Gilmore’s pose and expression?

What does Gilmore’s expression tell you about her character?

Trindall has used colour to create a certain atmosphere in his portrait of Gilmore.

How would you describe the colours in Trindall’s portrait?

What kind of atmosphere has the artist created?

Trindall exhibited another portrait of Gilmore in the 1937 Archibald Prize. In the earlier painting, Gilmore is seated against a dark background and holds a green hardbound book. In both portraits, you see a wedding ring on her left hand.

Look closely at Trindall’s portraits of Mary Gilmore.

Discuss the similarities and differences between the two paintings.

This portrait was painted the year after Gilmore was appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (D.B.E.).

How does the artist represent Gilmore’s achievements and status?

By 1961, at least thirteen portraits of Gilmore had been made by various artists. Most famously, she was the subject of a controversial portrait by William Dobell exhibited in the 1957 Archibald Prize. Gilmore wrote to the artist at the time saying, ‘The painting is far more important than the sitter. This painting will still be carrying my identity when my own work is forgotten’.

View Dobell’s portrait online at the Art Gallery of NSW.

Move your mouse over the portrait to

see the points of interest.

About the artist

Gordon Lyall Trindall was born in Maitland, NSW in 1886. At the age of 26, he gave up his barbering business to undertake art training at the J.S. Watkins School in Sydney.

By the 1940s, Trindall was widely known for his portraits and nudes, which commanded extraordinarily high prices. In 1943, he set a price of 800 guineas for his life-sized representation of Dawn; this was a record high asked by an Australian artist in a local exhibition.

Trindall stated that while modern art may be good, he himself could not make a living at it. Instead, his aim was to paint what the public wanted; 'sincerity', he said, 'is my guiding principle'.