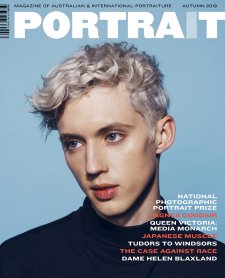

The international touring exhibition Tudors To Windsors: British Royal Portraits from the National Portrait Gallery, London traces the development and propagation of the monarchical image as an expression of dynastic, political and social power. Showing at Bendigo Art Gallery until 14 July 2019, the exhibition surveys nearly 500 years of the visual representation of monarchs and their families, accompanied by a retinue of their courtiers, favourites, ‘frenemies’, ministers, and deadly rivals. It brings together over 150 works spanning five royal dynasties, including paintings, sculptures, works on paper and photographs, revealing the royal countenance in all its iterations.

For royalty, then as now, sitting for a formal portrait was a time-consuming business. Such works – whether marking an important event, rendered as diplomatic gift, or commissioned to mark the bestowal of patronage or military appointment – were carefully calibrated. The zenith of art and power in alliance, portraits perpetuated the mystique of monarchy, consolidating a ruler’s prescribed image in the public mind. The monarch would often employ an official court painter, or ‘Principal Painter-in-Ordinary’, with a studio large enough to sustain high-level production of the royal image en masse, and often a painter of miniatures for more personal gifts. The modern era saw the photographic medium transform the dissemination of the royal image, signalling a new, more immediate, and more democratic approach to state portraiture.

Amidst the grandeur and pageantry of the monarch’s traditional role, the prospect of direct female rule was, for many centuries, met with ill-disguised dread and deep suspicion; it was considered ‘unnatural’, and incompatible with the premise of the ‘divine right of kings’. Amongst the parade of consorts, daughters and mistresses, Tudors To Windsors offers an insight into the manner by which court artists represented the ‘aberration’ that was the female monarch.

As the teenage Edward VI (1537-53) lay dying, his desire to consolidate Protestant hegemony in the realm led a ‘Devise for the Succession’ to be drawn up by his regency council, and issued as letters patent. In this document, Edward attempted to settle the crown on his first cousin once removed, Jane Grey (c. 1537-54), and exclude his half-sisters on account of their illegitimacy – the heir presumptive (and staunchly Catholic) Mary, and Elizabeth. Known as the ‘Nine Days’ Queen’, the ill-fated Jane was executed by her cousin Mary I (1516-58), England’s first undisputed (and later reviled) regnant queen.