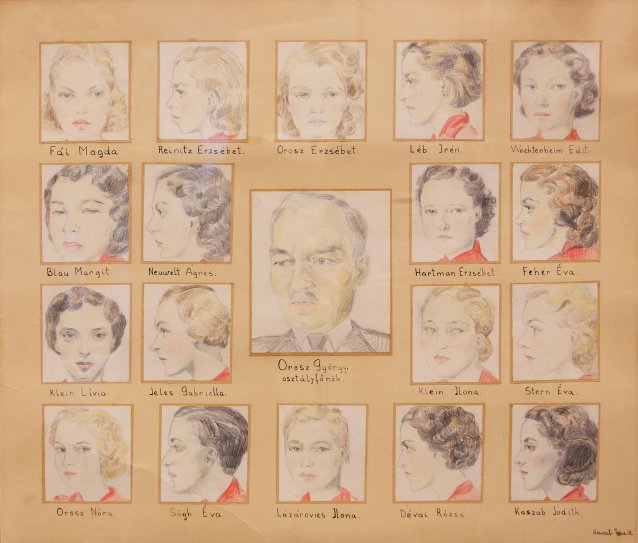

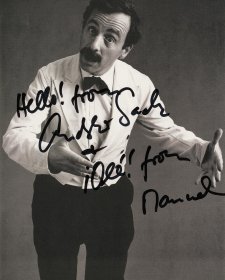

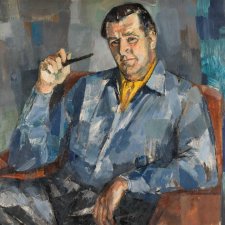

The summer of 1938 proved a life-changing one for Cassab. Having finished her high-school exams, she took a brief trip to Kassa, in Czechoslovakia’s ceded border region, to participate in a literary debate. It was there that she met her life-long love, a worldly and influential man eighteen years her senior, Janos (Jancsi) Kampfner. With each party equally smitten, they were engaged to be married within a month of meeting. Judy agreed to the proposal on the condition that Jancsi support her artistic pursuits, which he, a lover of the arts, whole-heartedly agreed to. Jancsi’s financial success and belief in his new love’s artistic gift would be the support she needed to develop her talents.

Upon her return to Beregszasz in March 1939 – following a year of study at Prague’s Academy of Art – the couple married, taking up residence in a beautiful home where Judy spent her days painting and drawing. However, their idyllic new life was soon fractured by the rise of Nazi Germany and the scourge of anti-Semitism. Detailed in depth in Brenda Niall’s biography and Judy’s diary entries, the atrocities the artist witnessed are horrific. Moreover, with Jancsi sent to a forced labour camp in an unknown location in Poland, the first three years of the couple’s marriage were marred by separation, and the anxiety of not knowing if they would ever see each other again.

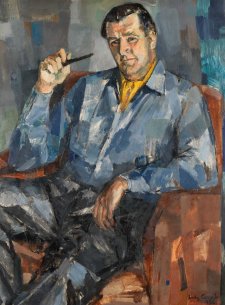

Post-war, still grieving for her mother – her memory ‘the bleeding wound I carry inside’ – Cassab found new impetus, having been reunited with Jansci, and now with a new addition to the family, baby János (John). The family moved to Szentendre, the artist colony on the banks of the Danube, where Judy met renowned painter Béla Czóbel – an artist known for his association with ‘The Eight’, the modernist group of painters in Hungary who were recognised for introducing a more radical, post-impressionist style into the country several decades earlier.

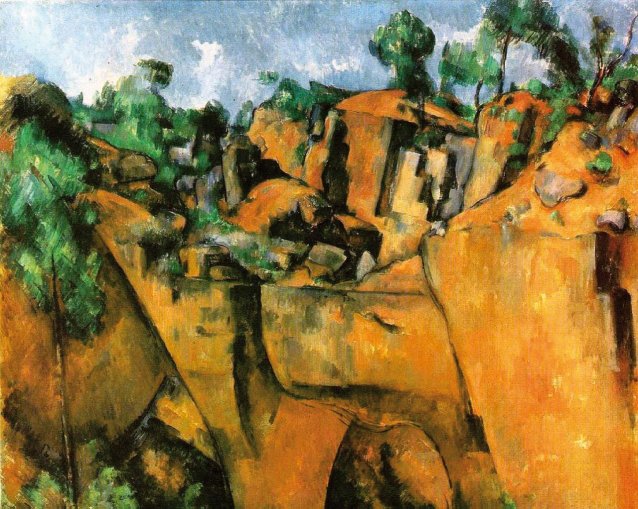

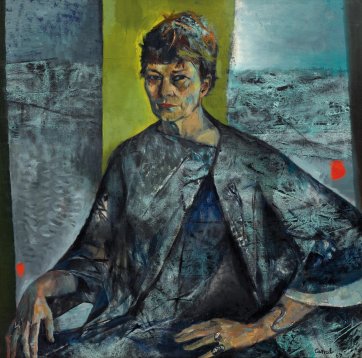

Czóbel’s influence was substantial. The only Hungarian painter known in France in the early twentieth century, he had participated in the Fauve Salon alongside Matisse, Derain and Dufy in 1906. Sitting for her portrait, Judy noted how Czóbel overpainted the entire surface time and time again, each portrait as fresh as the first sitting. Following this, she explored a fresh approach to her own composition, reflecting a more cubist style. Cassab’s time in Szentendre exposed her to other great painters. Jenö Barcsay discussed with her the importance of letting go, and Rudolf Diener-Dénes told her to ‘Take a rag dipped in turpentine and wipe the picture off, however much you like it. Next day, if you paint what you wiped off again, you can be sure it belongs.’

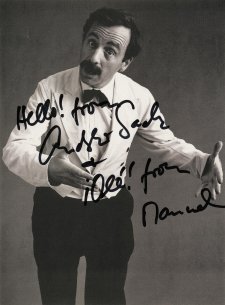

The sum of Cassab’s personal adversities, including the internment and deaths of family members, precipitated the family’s departure for Australia. Soon after her arrival in Sydney, she found another teacher to further invigorate and inform her practice, the renowned Hungarian painter Desiderius Orban – another member of The Eight. Orban, whose works reflected the influence of Cézanne and cubism, believed in Cassab’s ability: ‘You are talented, but you stopped somewhere in impressionism. You must forget that a table has four legs; use only what is essential to your picture. Forget the object.’ Orban taught Cassab the difference between harmonious colours and colour harmony, explaining that the first is a recipe everyone can learn, whilst the latter is achieved through one’s own discovery. Just as composition can be learned, design has to be found. Orban emphasised that this understanding would help Cassab find her own style, and challenged her to give up being ‘the artist’ for six months and paint only abstracts so that she could ‘feel’ her painting again.

Though Cassab had planned to visit Alice Springs in 1953, a bout of ill health delayed her, and it would be another six years before she arrived in the Northern Territory. Weeks before her first encounter with the remoteness of the outback, Judy noted her art didn’t fit into any category: ‘it’s not abstract enough for abstract, and it isn’t really figurative’. Reflecting on her approach to the canvas, she felt her foundation layer was very free and abstract, her second layer formed a theme, while the third layer connected the imagery. It was in this final plane, where the space was formed, that most interested Cassab.