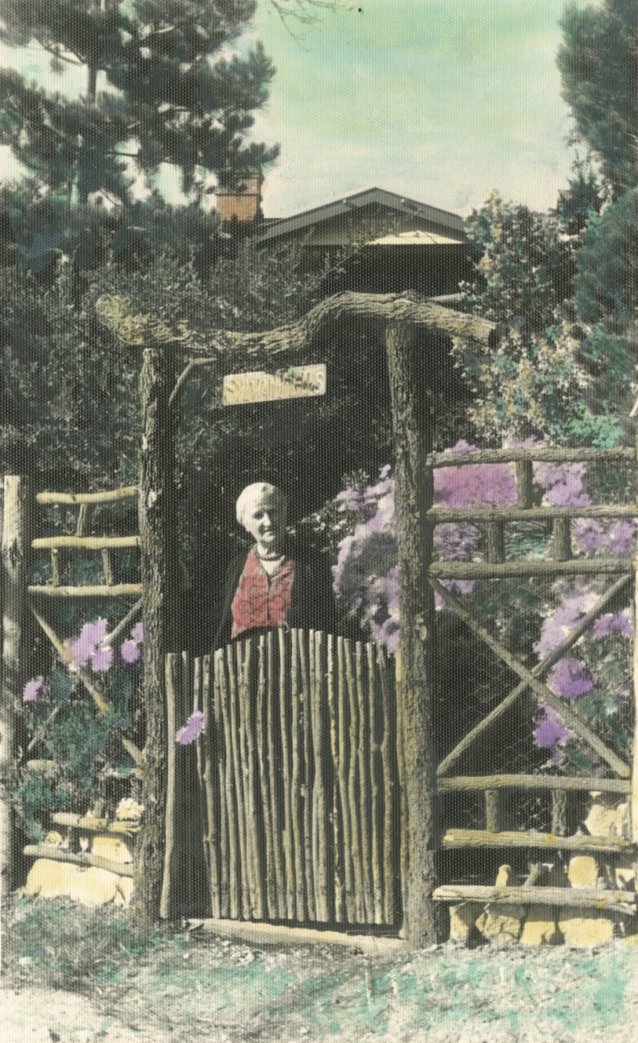

A petite, attractive older woman, scarfed, gloved and wrapped in a woollen coat, is captured in an instant with her hand and eyes raised, feeding two of the fluttering seagulls that encircle her. Labelled simply ‘Louise Lovely feeding gulls’ in the National Film and Sound Archive’s (NFSA) trove of stills portraits, the significance of the photograph was to emerge later as I rummaged through the Marie Bjelke Petersen archive in the Tasmanian Museum and Gallery Collection in Hobart. The picture of Lovely – ‘a forgotten darling of the silver screen’, standing in front of the Tasmanian Government Treasury building – was reproduced in a 1969 New Idea article, the torn fragment of which appears in Hobart author Bjelke Petersen’s scrapbook.

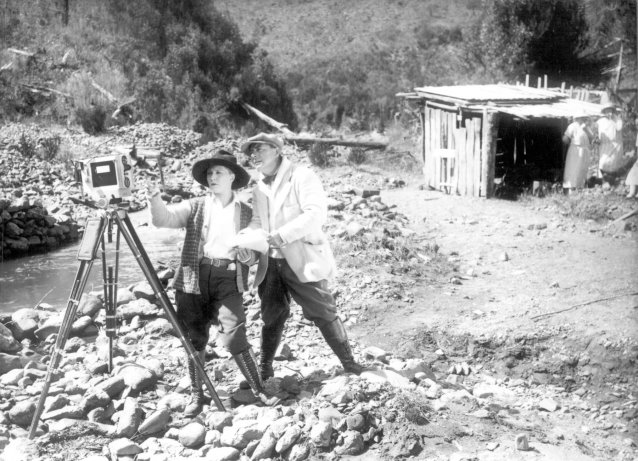

What was the connection between these two extraordinary and – even by 1969 – almost forgotten Australian women? The magazine article, headlined ‘Louise Lovely is alive and well and living in Tasmania’, reveals the intriguing link through a brief reference to Jewelled Nights. This was the title both of Bjelke Petersen’s popular fourth novel, published in 1924, and Louise Lovely’s first film in Australia following her return from Hollywood, released in 1925. A copy of the novel, replete with notes in Louise Lovely’s hand, sits in the NFSA’s Documents and Artefacts Collection; it is the genesis of the script for the film.