Reshid’s father Shefik Bey had been Turkish Ambassador in many European capitals, including Berlin, where Reshid was born, as well as Paris and London. Shefik was a gifted amateur artist who delighted in painting portraits of aristocratic women. In 1913 he married a great beauty, Florence Winter Irving, an Australian who came from a family in the Western District, where her father had been a member of parliament. She was then on the grand tour of Europe. When Turkey became a Republic, Shefik left the diplomatic service to become a portrait painter in Mayfair, London, where he celebrated beautiful women in pastels. Although Reshid was groomed by the Winter Irving family to become a wool buyer, he had been educated at home in various European embassies, and in painting schools in Paris and London. But at some point he decided to become a painter of portraits, still lives, and landscapes.

I had many memories of fabulous children’s parties arranged by Judy, who was an exceptional and daring hostess. One characteristic birthday party was held in Como Park where we practiced archery with real bows and arrows. We were aged ten and real weapons were never allowed at any other Australian party. At another we ate kebabs on real Turkish swords. Judy was a deeply generous person, who inspired creativity and energy in others. She was a classic beauty, and even as a mature grandmother was the sort of woman one focuses on across a crowded room. Like Florence Winter Irving, Judith Chirnside came from a Western District family and was brought up at her parents’ station, Carranballac, in Skipton, Victoria.

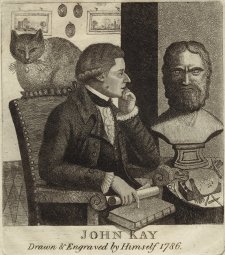

In some ways Reshid imitated his father’s career, although he had no direct experience as a child of the home countries in which his parents grew up, Turkey and Australia. In the end he chose in favour of his mother. Reshid arrived in Australia in 1937 at the age of 21. His mother Florence Winter Irving returned too, after thirty-five years of absence, only to be diagnosed with cancer. Reshid had been educated as an artist in Europe at the Chelsea Polytechnic, but took a refresher course at the art school at the National Gallery of Victoria after his arrival. Yet Reshid’s conservative French Salon style always remained alien to the main traditions of Australian art and portraiture. He held his first exhibition with his father at the Hotel Australia, in the Gold Room, on 18 May 1945. Alan McCulloch noted in his somewhat condescending review in The Age, 17 May 1945: “Shefik Bey specialises in pastel portraits of leaders of society. His objective is to reveal them in the best possible light, an objective which sympathetic understanding and natural good taste enable him to obtain. An adequate technique, combined with the exotic flavour of his Eastern origins, further enhances his chances of success.”

Reshid’s portraiture emerged from his father’s, but he attempted to be more complex. His self-portraits are questioning images, such as Self-Portrait as a Clown, shown in the Paris Salon in 1949, and Self-Portrait as a Man in the Fog, exhibited in 1959, in which he appropriated the famous image from Gustave Caillebotte’s painting in the Art Institute of Chicago. Still he never managed to cut it in Australia. The history of Australian art in the 1940s is always a narrative of modernism and artists like Reshid are ignored. Other immigrant artists came from Europe, recognizing Melbourne as a safe haven, away from war torn Europe. As a child I remember that Reshid and Judy were well known in society, but artistic success was always to evade him. Would a twenty-first century viewer or art historian be able to reconstruct the ideas that were, for the sitter, a part of the portrait experience, as recounted here? Almost certainly such speculation would be regarded as fanciful unless there was an account such as this.