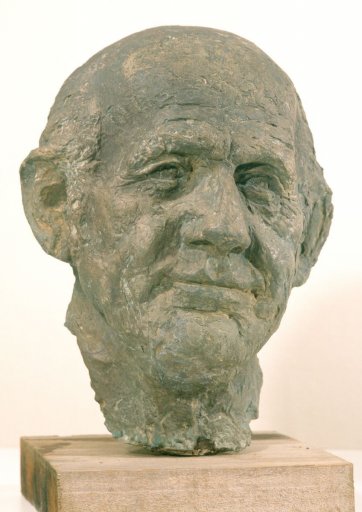

Lady McMahon reclines comfortably in a small armchair, her languorous pose traced in a long, partly foreshortened diagonal, further adjusted after the manner of an ‘angle shot’ in commercial fashion photography. The tilt of her head, the propped shoulder, the quizzical gaze, and the disposition of her carefully manicured hands suggest strength of character and a degree of tenacity that project through a gauze curtain of beguiling detail: the coiffure, the maquillage, the jewels, and, above all, the hosiery – sheer, flattering and unabashed. The title of Esther Ehrlich’s 1999 painting is Portrait of a Lady (Sonia McMahon), clearly a playful allusion to the sitter’s courtesy title, which derived from her late husband’s knighthood – Sir William died in 1988. Perhaps the title of the portrait, as distinct from that of the lady, can also be read as a not entirely un-sceptical nod in the direction of social distinction, while the literal form of the figure surely hints towards what was known 150 years ago as the grande horizontale. She was certainly not that, but, after her death in 2010 at the age of seventy-seven, Sonia McMahon’s obituaries were almost unanimous in deploying the loaded term socialite.

Who or what is a socialite? Someone who is prominent in fashionable society, is perforce fond of social activities and entertainments, and uses such prominence to work charitably for the common good? Or any two of these in combination? Maybe. The term is paradoxical because, like tycoon or statesman or celebrity the person to whom it is applied would probably not themselves think to write it in the space on the form marked ‘occupation,’ while a person who did self-identify in this way (without irony) – admittedly this was before Kim Kardashian – is, I suspect, in each case not likely to be a bona fide specimen. Nevertheless the term socialite is obviously class-specific, and must to some extent involve glamour. It is also a kind of spotlight term projected into the upper reaches from below, for the earliest reference to socialite in the Oxford English Dictionary comes in 1909 in the Bay-Area Oakland Tribune. Importantly the term therefore originated as a gilded-age American colloquialism, and has ever since been closely allied with tabloid journalism and what used to be called the social pages. It seems also to coincide with the transatlantic moment when society ceased principally to mean ‘high society,’ in the exclusive sense of ‘court and social,’ and broadened radically to embrace the fundamental state or condition of living or associating with others across a whole community. The quotation history of socialite, n., has duly evolved between the first and third editions of the OED, migrating from associations with aristocracy and a measure of artistic bohemianism, but definitely exclusiveness, towards the frivolous, the shallow, and the sybaritically rich. These are surprisingly moralising editorial modifications, and not I think entirely congruent with current usage in Australia.

There is also the question of where exactly in the upper reaches the socialite spotlight falls, for no doubt there are still people who would be horrified to find themselves so designated by the press, either because this would be to penetrate a jealously guarded cordon sanitaire of privacy, or else to imply a degree of counter-jumping vulgarity, or a lack of the kind of discretion that is synonymous with tightly closed social circles such as those of the Alexandra or Queen Adelaide Clubs. At the very least, a socialite would appear to be able to pass freely in and out of these (I am guessing), but also to dwell with equal comfort in far more visible arenas, on red carpets, and in the glare of multiple flashbulbs. Some years ago I asked an Indian member of parliament, who, belonging also to a princely family, was enthusiastically Anglophile, whether she followed the test cricket; India was then on a winning streak. She smiled faintly, shook her head, patted my wrist indulgently, and replied with the single word: ‘Polo.’

A cursory scan of Australian Newspapers Beta, meanwhile, that awesome resource made available by the National Library of Australia, shows that SOCIALITE will most likely appear in mid-twentieth-century newspaper headlines followed by the words WEDS, DIVORCES, ARRESTED, INDICTED, KILLED, FOUND DEAD, or QUIZZED ON RED AGENTS. It also tends to attract qualifiers, such as POPULAR, WEALTHY (fifty years ago wealth alone did not by any means define a socialite), SYDNEY (there being apparently a dearth of socialites in Kalgoorlie, Ouyen, Cunnamulla, etc.), PROMINENT, BEAUTIFUL or HANDSOME, because, until recently, socialite has been a gender non-specific term, there being numerous instances in the headlines of HUSBAND OF and WIFE OF.

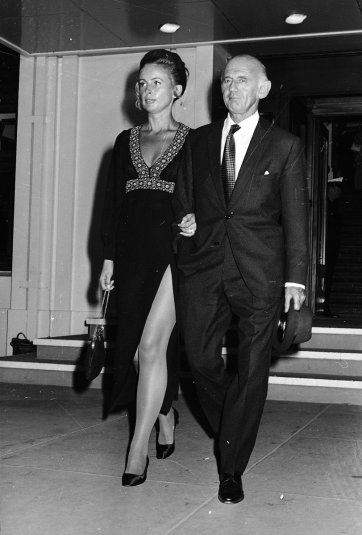

Yet Sonia McMahon, ‘socialite,’ was also the wife of the twentieth prime minister, and the granddaughter of William Matchett, himself one of the richest men in Australia and a prominent grazier in New South Wales. She was also, before her marriage in 1965, a qualified occupational therapist. To some degree she was also a fashion-plate, having worn that dress to the Nixon White House. Yet I cannot think of another wife of an Australian prime minister who would ever have been described by our press as a socialite, with the possible exception of Dame Zara Bate (the widow of Harold Holt) or Ethel Bruce, although Lady Bruce was rather too tweed-coat, church-bazaar and sensible-shoes for that descriptor, and in any case it is debatable whether it would have been used here as early as the 1920s. Nor can one think of many wives or spouses or partners of former prime ministers who would have actively sought the distinction.

Would Lady McMahon have been described as a socialite had she not been married to Sir William? It seems distinctly possible. A fruitful comparison could be made between Sonia McMahon in Sydney and Susan Rossiter Peacock Sangster Renouf in Melbourne. Lady Renouf was recently described by the Sydney Morning Herald as ‘the well-travelled, much-married socialite,’ and it is not inconceivable that had Liberal Party politics developed along different lines, and had her first marriage not been dissolved when it was (1977), Susan Peacock might also have been the wife of a prime minister. So the dilemma we face, as with many other spouses or former spouses of high officials, is that in the National Portrait Gallery’s database Sonia McMahon currently dwells in the first level distinction of Government and leadership – prime minister’s wife, deeply unsatisfactory in this day and age. And in many respects, Sonia McMahon conforms happily to all the accumulating senses of socialite to which I have referred. She made frequent appearances in the Australian Women’s Weekly and Woman’s Day. She was often photographed sipping champagne with friends in the enclosures at Randwick and Flemington. She was a member of numerous boards and an active patron of many charities, including the National Brain Foundation, the Sydney Children’s Hospital Foundation, the Australian Cancer Research Foundation, the Microsearch Foundation, and Australia’s Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Association.

Through the twenty-one months of their tenancy in The Lodge in 1971 and 1972, Sonia McMahon joined only two other women who have ever given birth during their husband’s term of office as prime minister, Margaret Fisher (in 1908) and Dame Enid Lyons (in 1933). Many more, however, have felt keenly, as Sonia McMahon certainly did, the competing demands and needs of sometimes very small children and a busy schedule of public commitments dictated by their husband’s commission to high office. The family was obliged, meanwhile, to endure the slings and arrows of a political life to which they found themselves wedded, as much as they were from time to time permitted to partake in moments of victory. This, too, was part of the experience of Sonia McMahon when in 1971 Billy McMahon successfully stood for the leadership of the Liberal Party after John Grey Gorton resigned, duly took office as prime minister, but was defeated by Gough Whitlam in the general election that took place at the end of the following year. Far more of the personal resilience made necessary by living through and with those events – Sonia McMahon was twenty-five years younger than Sir William and only forty years old when his political career suddenly ended – has found its way into Esther Erlich’s Portrait of a Lady (Sonia McMahon) than the soubriquet, the mixed message, the label, the veneer of ‘socialite’ would ever allow.

Lady McMahon is survived by two daughters, Melinda and Deborah, and a son, the actor Julian McMahon.