Looking at reproductions in the many books that have been produced on Avedon’s photographic work, one is struck by their clarity, their bold composition, in many there is a sense of motion either in flight or arrested. What do these photographic portraits reveal to us about the lives of their subjects?

Avedon has emphasised the complicity of his portraits to the effect of reality. In 1970 he wrote this: ‘My photographs don’t go below the surface. They don’t go below anything. They’re readings of what’s on the surface. I have great faith in surfaces. A good one is full of clues.’ Now, in the 21st century we might take photographs at face value. We are right to be suspicious of photographic veracity in an age where the photographic image is constructed, Photoshopped, and where images of the human face and body are idealised. Photography is ubiquitous and everyone can make photographs. In this saturated environment what can a photograph tell us? How can we go deeper? How can we make a connection with the subject of a photograph?

Over the course of his working life Avedon produced several ambitious projects. Shortly after the Second World War Avedon was commissioned by Life magazine to document street life in New York City. After nine months of taking pictures with his Rolleiflex, Avedon reconsidered publishing the photographs. He returned his advance and held back the images until he included them in his book An Autobiography in 1992. The images possess an air of uncertainty and ambiguity. People are photographed in mid-stride, individuals and couples are arrested in time. They make guarded eye contact with Avedon the photographer, and with us.

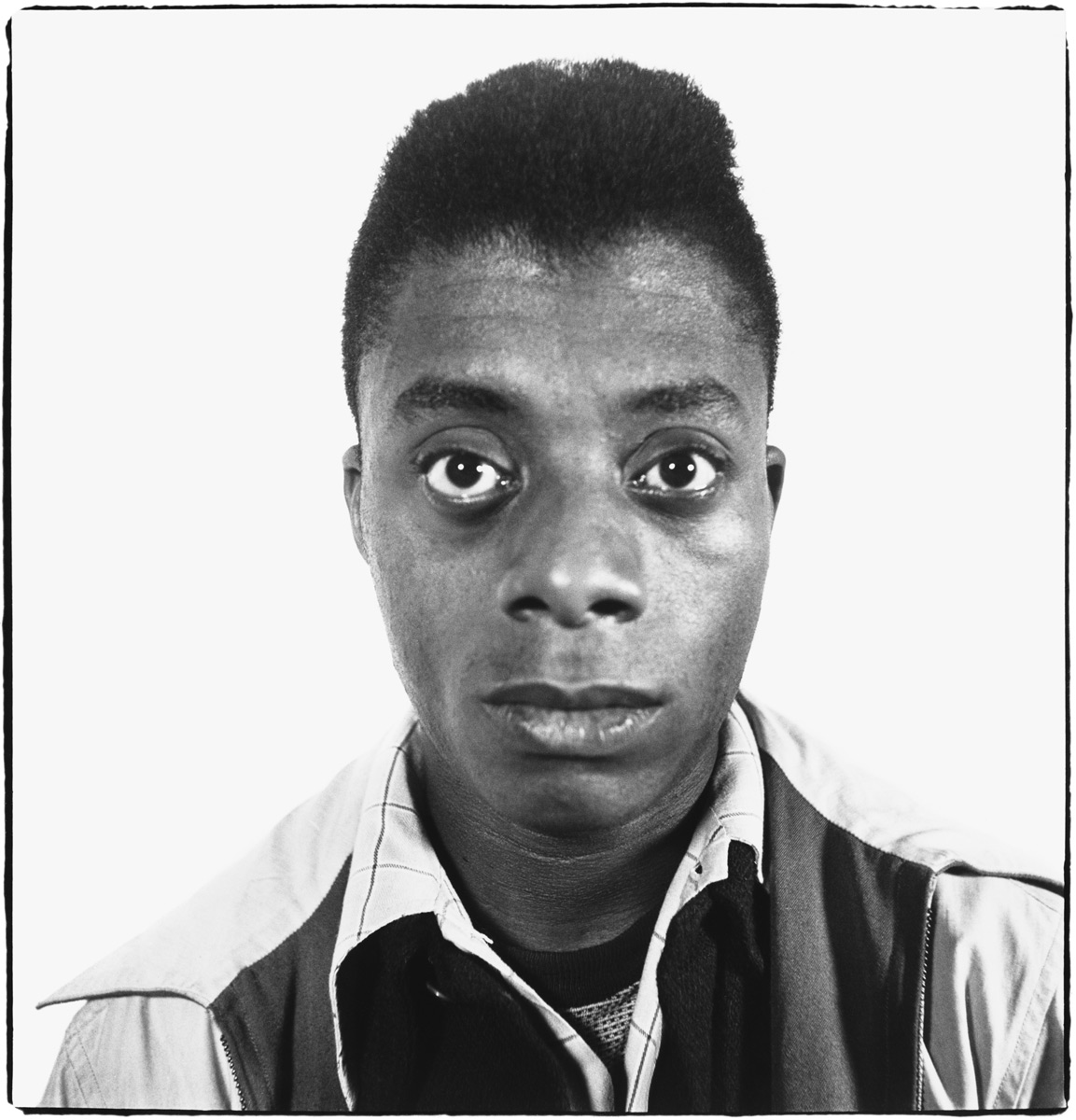

Avedon conceived a book of photographs and text titled Nothing Personal, a collaboration with James Baldwin, writer, and Marvin Israel, designer. Avedon was widely known for his fashion photography and the book’s publication in 1964 was met with hostility for its unflinching look at American society. The book included portraits of mainstream and countercultural leaders across the political spectrum, alongside candid, yet compassionate, images of patients at the East Louisiana State Mental Hospital and atmospheric photographs taken at Santa Monica Beach.

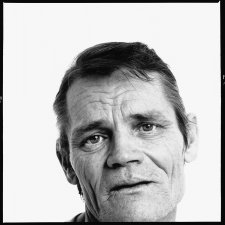

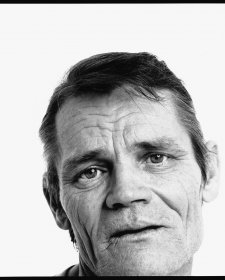

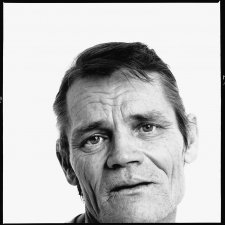

In 1978 Avedon embarked on a portrait chronicle spanning five years. The Western Project, commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth Texas, resulted in a compelling series of portraits titled In the American West. Avedon’s producer for the project Laura Wilson reflected on the project thus: ‘Right from the start, Avedon chose men and women who work at hard, uncelebrated jobs, the people who are often ignored or overlooked. He searched for what he wanted to see and his choices were completely subjective.’

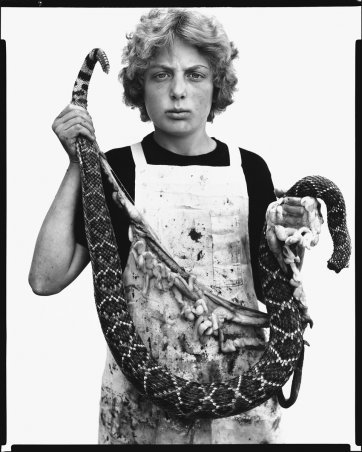

Avedon’s portrait of Boyd Fortin, an adolescent boy holding a gutted rattlesnake, began the Western Project. In the town of Sweetwater, Texas, at the Rattlesnake Roundup (held annually since 1958), Avedon found the boy working with his father skinning and gutting rattlesnakes. In three sessions over two days Avedon photographed Boyd Fortin against a large sheet of white paper taped to an exterior wall of the Nolan County Coliseum. As with all of the photographs selected to represent the Western Project, the portrait of Boyd Fortin was printed at 40 x 50cm for reproduction in the exhibition book.

Photographic printer Ruedi Hofmann has reflected on bringing out the subtle elements in these portraits: ‘We would have conversations at the table after printing – we’d have this stack of prints, printed in several different ways. Darker lighter, more contrast, less.’ Avedon’s instructions were not technical or even aesthetic. They were based on achieving the communication of an emotional state. ‘He would tell me to make the person more gentle,’ Hofmann recalled, ‘or make the person seem more tense.’ This was an invitation to interpret the photographs ‘to try and understand more what the intent was’.

For the exhibition the prints were produced largescale, using an enlarger that projected the images against photographic paper fixed by magnets to a metallic wall. Encountering the prints in the exhibition at large-scale adds a compelling and unique sense of drama to Avedon’s concise visual composition. The portrait of Boyd Fortin is over one and a half metres high.

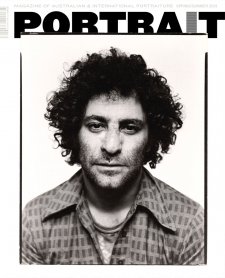

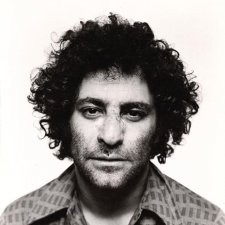

Avedon’s fashion work from the 1940s and 1950s is characterised by captured energy. In the book Nothing Personal his photographs are infused with movement. In 1969, beginning a portrait project that sought to document the spectrum of prevailing attitudes of the 1960s and 1970s in North America, Avedon posed for a self portrait to test the visual and technical format of the portrait series.

He stood evenly lit against a white backdrop facing his camera, establishing his new visual style. It is in this mode that young Boyd Fortin stands, raising the headless rattlesnake and holding it in front of himself as if it were a mechanical device or a musical instrument. Determination or consternation flashes across his face. The image of the boy holding the snake, removed from its visceral real-life context of the Rattlesnake Roundup possesses grandeur and purity. Avedon has refered to this image as being akin to a dream, a surrealist painting. ‘A portrait is not a likeness,’ Avedon says. ‘The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.’