With more than 10,000 artworks acquired over thirty-two years it may come as a surprise that portraiture makes up just three percent of the Artbank collection.

Initiated in 1980 as an art support program, Artbank, the Australian Governments art rental program, has a collection that includes works by over 2000 Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian artists. The collection includes works in all media with subject matter ranging from landscape and abstraction to sociopolitical and cross-cultural commentary.

The acquisitions, which number around 250 annually, primarily focus on works by artists in the early stages of their career and are only purchased from the primary art market which in turn supports the art sector in Australia. The works are available to rent on an annual basis to Australian diplomatic posts overseas, government and corporate offices and private residential clients. The revenue from the rental funds the operating costs of the organisation as well as the annual acquisitions budget of around $1million, making Artbank one of the largest supporters of Australian art in the country.

The small number of portrait works in the collection may seem unusual for such a large national collection, especially as portraiture is often considered the most accessible of art forms and annual portrait award exhibitions, such as the Archibald Prize, are hotly anticipated and overwhelmingly popular with artists and gallery visitors alike.

However, the truth of the matter is, portraits don’t rent. And for a fully selfsupporting art organisation whose core business is the rental of its collection, the works acquired are not only some of the best examples of contemporary arts practice in the country, but must also have an appeal for Artbank’s clients.

Perhaps the simplest answer lies in the fact that the majority of Artbank’s works are rented for display in government and corporate offices, and most people don’t want to be watched over while they’re working – by an actual person or the likeness of one. In addition, portraits are intimate representations of a person and their display usually indicates a relationship either to the business or the resident.

With this in mind, when considering

portraits for the collection, Artbank’s Curators look for works that take an alternative approach to what is traditionally considered a portrait. Works acquired in recent years are often humorous, tell personal narratives or comment on contemporary culture.

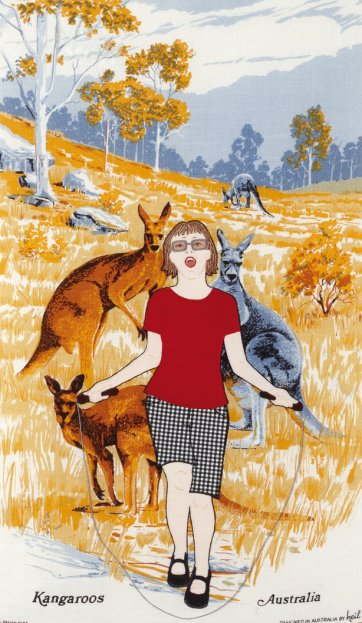

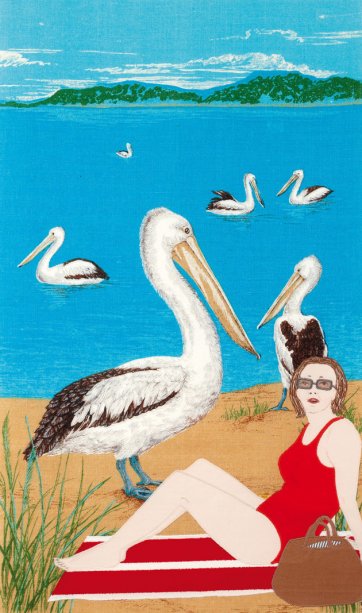

Self portraiture is a consistent subject matter in Adrienne Doig’s often humorous works. Swimming with Platypus features rudimentary Australiana imagery, with its depiction of recognisable native fauna and the accompanying text detailing the biological characteristics of the species. As a readymade tea towel, this would be the kind of item found in a tourist shop almost anywhere in Australia. There is one exception here: the inclusion of the artist herself, diving diagonally through the composition in a vibrant red swimsuit. The playful insertion of the artist elevates the work to something far more interesting and complex than what is usually associated with kitschy tourism imagery.

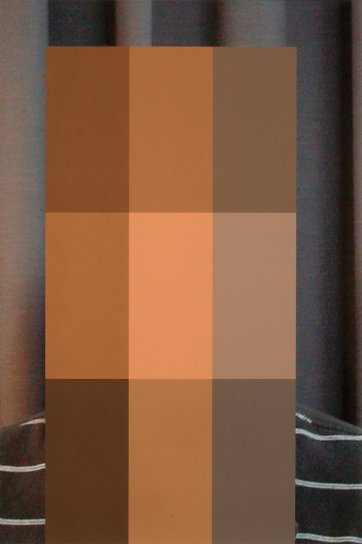

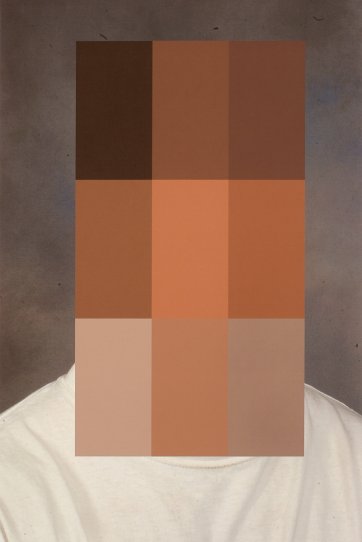

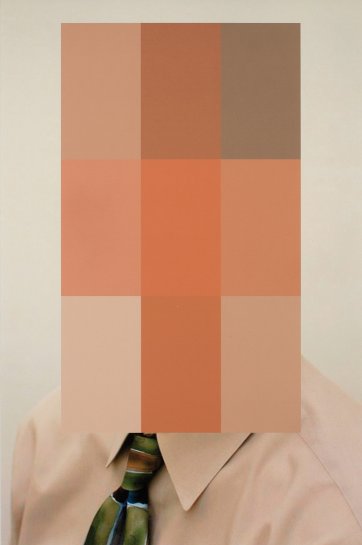

For the production of Chris 01, 09 and 12, multidisciplinary artist Chris Fortescue entered the keyword ‘Chris’ into internet search engines to retrieve hundreds of thumbnail images – a process he refers to as ‘image mining’. The thumbnails, typically low quality and containing less than 50KB of data, were systematically manipulated to create images with a grainy, moody patina. In the resulting portraits the face of each ‘Chris’ is reduced to nine simple blocks of colour, rendering the face unidentifiable so that Chris in the portrait could be one or many possible selves.

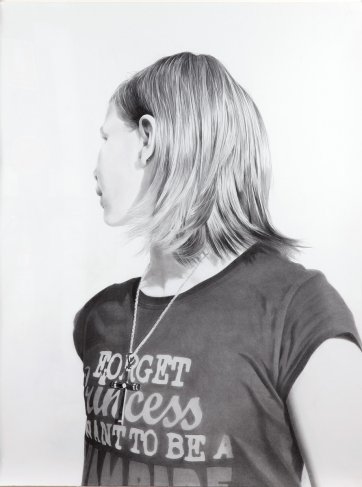

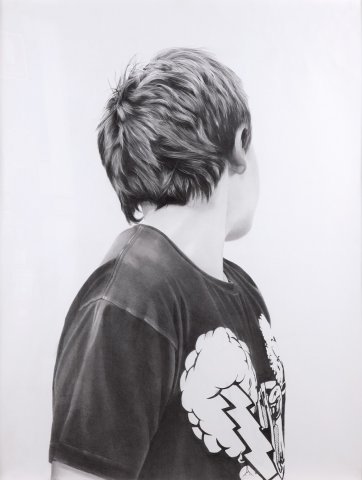

In recent years there have been several critically acclaimed exhibitions of drawings, turning the interest of curators to artists working within the most fundamental and personal of art disciplines. Henry and Brodee are from a suite of exquisitely rendered drawings by Melbourne-based Mark Hislop of his nine year old son Henry and his friends. With the face turned away, Hislop presents an alternative reading on the traditional portrait head, instead focussing on the hair, the position of the body and clothes to convey a sense of adolescent angst.

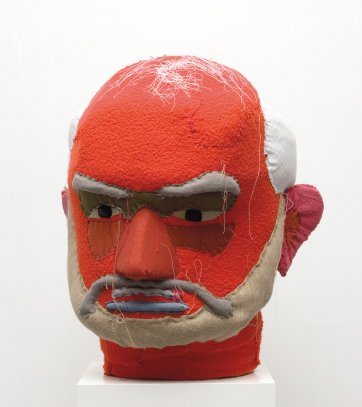

Primarily known as a painter, Alan Jones’s practice has always explored notions of identity, with self portraits and family members often at the heart of his work. In his 2007 series, The Joneses, each member of his immediate family, in this case his father Mike, has been immortalised in handsewn figures made from recycled fabric, capturing to an uncanny degree, their likenesses. Even with its austere facial expression, the work is striking yet playful and created during a period in which a number of prominent male artists were exploring notions of masculinity in contemporary society, often working in traditional craft mediums. The work has been on display in the CEO’s office of one of Sydney’s leading stock trading firms. A brave choice, though somewhat intimidating for those attending a meeting.

Artbank began acquiring video works in late 2007 and has since acquired work from some of Australia rising new media stars. Much of Laith McGregor’s practice, across various medium explores notions of masculinity and in particular, its relationship with facial hair. In his drawings, flowing beards become large bulbous growths that almost engulf their owners, while his video Maturing is a parody of portraiture and performance. Maturing is a close up of McGregor drawing a beard onto his own face to the point of mania while acting out the personalities he imagines to accompany the various styles of facial hair.

The disruption of meaning in the title for Pete Volich's body of work, Thoughts from the nap in an afternoon couch, parallels the chaotic images of piles of clothes strewn over various armchairs. At first these images appear as documentary photographs; an intimate view into someone else's mess and their crumpled wardrobe. However, it becomes apparent that the disorder is instead a careful and subtle assemblage that positions the clothes to embody their owners. These quirky personifications take an alternative approach to portraiture, emphasising how we use material goods to define our appearance and in turn our sense of self.

While unconventional at times, the portraits in the Artbank collection are representative of the current practices of contemporary artists, and how they are innovatively engaging with one of the oldest art traditions.