Fashion and advertising in the 1990s set the slick against the slacker in the battle of glamour vs grunge.

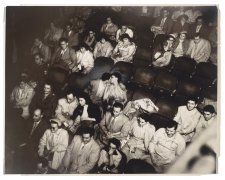

Alternative culture in the 1990s was inflected by a sense of cynicism towards consumerism, a slacker aesthetic and a taste for grunge music and fashion, exemplified by Canadian writer Douglas Coupland’s popularisation of ‘Generation X’.

This cool disengagement was quickly picked up by the advertising industry in a kind of reverse psychology that said ‘We know you know the lifestyle we’re selling is fake.’ Classic teen rebellion mirrored a 1950s motif in poet-rockstar Kurt Cobain of the band Nirvana. Like James Dean, Cobain was sensitive and sexually ambiguous. They each embodied the awkward and intense feelings of their respective generations. Dean died in 1955 aged twenty-four crashing in his Porsche. Cobain used a shotgun to take his own life in 1994, he was twentyseven. Cobain and his fellow poets offered emotional rawness, inclusivity and acceptance of difference, with corresponding fashion cues including op-shop clothes, jeans and canvas shoes.

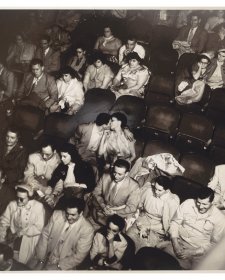

The 1990s grunge aesthetic was a strong contrast to an elevated glamour that was finely calibrated by American clothier Calvin Klein, exemplified by the purified, minimal, muscular body of youthful Mark Wahlberg wearing Calvin Klein underpants. Klein employed influential photographers Bruce Weber and Herb Ritts to create innovative images of contemporary beauty for billboards and magazines.

Calvin Klein’s ad campaigns celebrated idealised eroticism amid the cultural comprehension of HIV/AIDS. Philosophers and art historians debated the aesthetics of abjection and galleries presented exhibitions of grunge art. Millions were drawn to the escapism of Titanic, Jurassic Park and Star Wars: The Phantom Menace.

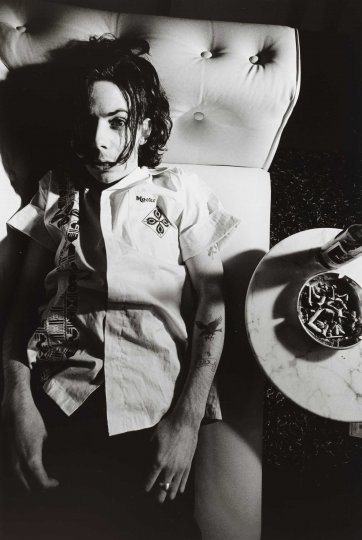

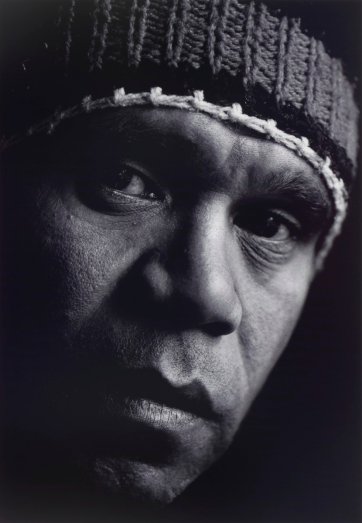

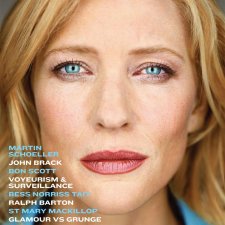

The National Portrait Gallery is displaying a suite of six photographs that feature prominent Australian personalities who reflect the glamour and grunge of the 1990s and early 2000s. The display includes some newly-acquired portraits including singer-songwriter Archie Roach by Bill McAuley and novelist Christos Tsiolkas by John Tsiavis. Megan Gale by Ellen Dahl and Nicole Kidman by Irving Penn are depicted in satiny-smooth silver tones; Kidman’s portrait evokes the glamour of classic Hollywood, Gale’s the clarity of contemporary Australian female beauty. Actor Noah Taylor has been photographed by Ross Honeysett dishevelled and emotionally exposed. In 2000 a young Australian actor by the name of Heath Ledger was shooting the movie A Knight’s Tale in Prague where he was photographed by Bruce Weber for Vanity Fair magazine. Weber captures Ledger comfortably tousled with a gentle smirk, boyish and warm. A bit glamour, a bit grunge.