‘The imitator or maker of an image’, according to Socrates, knows ‘nothing of existence. He knows appearances only.’ Socrates suggests that such artists might describe kindness without ever understanding the truth of it; they know the appearance of things but not the reality.

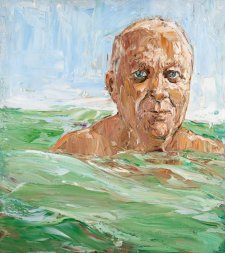

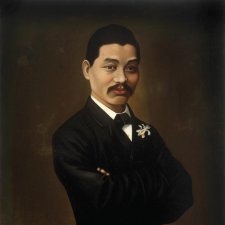

Artists grapple with the notion of how to create a portrait that depicts physical likeness yet also conveys an understanding of the character of the sitter and the essential humanity of their subject.

There are a number of devices that an artist can use to suggest the inner nature of an individual: idealised features, pose and posture, gesture, emblems of rank, clothing and other social signifiers as well as symbolic and allegorical objects can give clues to personality and achievement. The emphasis on mimetic likeness can be countered and complemented through formal means – colour, composition, distortion – so that artists can introduce emotional indicators into a portrait. The tension between surface appearance and inner being is the essence of imaging identity.

Best known for their uncompromising paintings of the human body, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud might equally be known as significant portrait painters. While they were close friends and worked closely together, especially in their early years, it is surprising to learn that their work has not been shown together. Both artists gave life to expressive figuration, imbuing the figure and their portraits with powerful emotive forces and psychological insight that was post-Freudian by definition. According to Bacon, ‘The creative process is a cocktail of instinct, skill, culture and a highly creative feverishness. It’s a little like making love, the physical act of love.’ Bacon’s portrayals of his friends are often as violent as they are loving. His tortured paintwork and surreal compositions speak of life as an almost hallucinatory experience. His dissembled portraits are depicted with a trembling and passionate intensity. Bacon painted his immediate circle – friends and lovers – and took very few commissions. He rarely painted from the motif, preferring to work from photographs. claiming ‘I don’t want to practice before them the injury that I do to them in my work.’

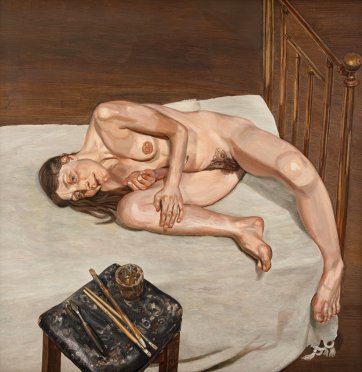

Bacon’s traumatic distortions contrast with Freud’s carefully modelled figures. Despite the initial appearance of realism, Freud’s paintings are expressionistic and painterly. Freud recalls that ‘Francis Bacon would say that he felt he was giving art what he thought it previously lacked. With me, it’s what Yeats called the fascination with what’s difficult. I’m only trying to do what I can’t do.’ Freud attempts to paint not just what he sees but what he understands as truth. Like Bacon, his subjects are often the people in his life; friends, family, fellow painters, lovers, children. As he has said, ‘The subject matter is autobiographical, it’s all to do with hope and memory and sensuality and involvement really’. The violence in Freud’s portraits does not compare to that in Bacon’s paintings but the frankness with which he details the face and bodies of his sitters is searing. ‘For me, the paint is the person’ said Freud. Each artist attempts to hold likeness and character in balance but each takes a very different, diametrically opposed, approach. Bacon works from the inside to the outside surface, usually in a single campaign while Freud, the master of observation, copies the skin of the body, working up character over prolonged sittings. Bacon’s portraits of friends and lovers form a biography charged by emotion. His terrifyingly distorted images of George Dyer or Isabel Rawlings document the violence of his troubled emotions and the instability of his relationships as well as his own disconnection with the world.

The existential mood was not unique to Bacon but framed by the Cold War consciousness of atomic annihilation. An awareness of mortality is ever present in Bacon’s paintings and there is a whiff of decay in his equation of flesh with meat. Freud’s naked bodies also preserve the visceral tang of the flesh but because his figures are anchored into their environment, there is a degree of stability and the impression of, if not calm, then of stillness. Both artists return to the same subjects, painting change and continuity. Thinking of Freud’s taut paintings of his first wife seated in a claustrophobic space, anxiously clutching a kitten or a rose, writer and critic Herbert Read called him ‘the Ingres of Existentialism.’

The long periods of observation that go into each work are evident in the concern with surfaces and detail. ‘I had hoped’, remarked Freud, ‘that if I concentrated enough, the intensity of scrutiny alone would force life into the pictures.’ Realising that observation was not enough, Freud dispensed with the thin, flat, uninflected rendering of his early work to adopt a more painterly style, standing instead of sitting to paint, using stiff hog bristle brushes and thicker paint: ‘I want my paint to work as flesh’. Freud’s careful, relentless facture melds scrutiny and enquiry and forces a passivity on his subjects that approaches confessional exposure.

It is tempting to think that Bacon’s familiarity with his subjects allowed him to work from the inside out, that his personal connections and feelings dictated the look, but there is some irony in saying this as he inevitably worked from photographs. Deleuze’s concept of Faciality (face as identity) is ignored by Bacon whose subjects are defined by more than the set of facial features. Faces are and bodies exploded, broken up to be remade complex and dynamic rather than as a composite of signifying structural forms. Bacon felt that the presence of a sitter might inhibit his freedom to interpret their presence on the canvas. In contrast, Freud’s insistence on working from life – he is notorious for the length and number of sittings he requires to complete a work – compels attention to the subtle topography of surface. From the familiarity with the skin of the body, Freud works inwards, learning expression, mannerisms and pose to build a body as expressive as a face.