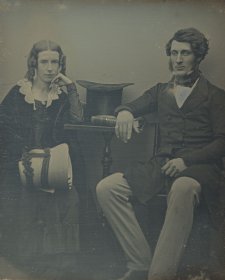

To look closely at a fine example of a daguerreotype can be charming and unnerving at the same time. Charming because of their gem-like presentation in small, velvet-cushioned cases and for the evidence they provide of lost fashions in such things as frocks, furnishings and facial hair.

But unnerving too for the incisive way they confront a viewer with the faces of subjects that have been dead for more than a century. Still and cold, but almost breathing. And looking you right in the eye.

The first commercially viable form of photograph, the daguerreotype is cited as the process that initiated a revolution in portraiture, the first of many technical developments which, by the 1860s, had made portraits things acquirable by everyone. The daguerreotype process found its way to Australia within two years of its invention in 1839. In 1842, Australia’s first professional photographer, George Baron Goodman, set up shop with a ‘photographic apparatus’ in a studio situated on the roof of a Sydney hotel.

On its debut here, as elsewhere, the daguerreotype was gushed over as an exciting new method of image making. Early portrait photographs were seen as truer images than those achieved by the artifice or fakery of painting, and were described with the language of science: not as likenesses that were made or created, but as specimens ‘captured’ or ‘taken’. Daguerreotypes were also prized for the precision with which, as if by some sort of alchemy, images of such stillness, clarity and finesse could be fused from iodine and mercury onto small, silver-plated panels of copper.

‘We have ourselves witnessed the execution of several portraits’, boasted the Maitland Mercury in November 1846 of Goodman’s work, ‘and, in addition to their being excellent likenesses, there is a degree of finish about them that is impossible to be appreciated unless seen.’ In addition to their curiosity value, daguerreotypes had the appeal of being slightly more affordable than painted miniatures. Goodman’s price of one guinea (not including the cost of a case) was declared by the Sydney Morning Herald to be ‘extremely moderate – a portrait, frame and case being less than the cost of a new hat, or a box at the theatre.’ Early portrait photographs are thus considerably more than haunting, two-dimensional images. They are artefacts loaded with meaning which, in their physical properties, process and presentation, reveal something both of the public times they were created in and of the sensibilities of their subjects.

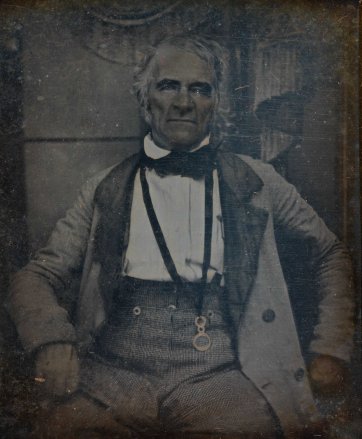

All such qualities are perfectly demonstrated by the daguerreotypes included in a fine selection of portraits recently donated to the National Portrait Gallery by the descendents of their subjects. Charles, Richard, William and Mary Windeyer are sitters representative of those commonly preserved in early Australian portraits; members of a notable colonial family and each intriguing for their individual contributions to spheres such as journalism, politics, law, education, and women’s rights. The gift of nine portraits also includes watercolours and miniatures, and presents four subjects across three generations of a family whose association with Australia commenced with the arrival of Charles (1780-1855), a journalist who emigrated in 1828 with his family and who by the end of his life in the colony had served as a magistrate and the first mayor of Sydney. Charles’s eldest son, Richard (1806-1847), like his father, started out in professional life as a reporter but rose to significance in New South Wales as a barrister, politician and landowner.

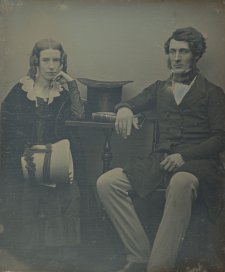

Richard’s son, William (1834-1897), followed his father and grandfather into law and achieved renown in his position as a Supreme Court judge as well as for the social reforms supported by him and his wife, women’s rights campaigner, Mary Windeyer (née Bolton, 1837-1912).

But beyond the pedigree of these subjects for their history-shaping achievements is the potency of this group of their portraits as a hint at the way preferences in family portraiture were redefined with the advent of photography. The exposure time for a daguerreotype might have meant a sitter’s braced submission to a minute or two of absolute stillness – resulting in what some considered to be portraits of cadaverous or ‘deathlike aspect’ – but photography’s other qualities were of sufficient appeal for it to gradually supplant painted miniatures as a means of preserving or documenting family connections and personal feelings. Daguerreotypes, akin to miniatures in their treasureable, touchable presentation, were just as suited to the purposes of talisman or keepsake, mirroring a holder’s very experience of cherishing and intimacy. Like other miniatures and early portrait photographs residing in Australian collections, these portraits of members of the Windeyer family are part of the material culture of colonialism, small, quiet records of the private side to public lives and endeavours.

Portrait miniatures are objects laced with longing or desire, a characteristic exemplified in Richard Windeyer’s portrait by the Royal Academy-trained miniaturist Charles Richard Bone. The eldest of his parents’ children, Richard remained in England to complete his education when his parents and nine siblings left for Sydney in 1828. Seven years later, a barrister, husband and father, Richard joined his family in New South Wales where he was soon admitted to the bar. He acquired his first piece of land on the Hunter River in 1838.

Within a few years he had graced his estate, Tomago, with a stone mansion and had begun investing large sums in various schemes including swamp drainage, winegrowing and livestock. Some projects failed, some flourished. Eventually, Richard’s energy as a member of parliament and taste for what his wife Maria termed ‘country luxuries’ eventually contributed to the anxieties, overwork and ill health that brought about his death aged only forty-two.

The miniature, however, shows him as a young, up-and-coming gent. Though undated, its pendant format and pinkcheeked sensitivity suggest that it was painted in anticipation of his family’s departure for the colony. A lock of Richard’s hair, curled into the shape of a fleur-de-lis, is encased behind the portrait, emphasising its function as a physical trace of a distant loved-one: an object designed to be worn beside the skin, kissed, clasped in the hand, or carried in the pocket of a waistcoat.

Indeed it was through being so handled that miniatures were less subject to damage during something as risky and fetid as an 1820s sea voyage. That objects of such delicate stuff as ivory and watercolour could traverse great distances unscathed is something that comes to mind on viewing another of the four miniatures included in the Windeyer family gift: that of Richard’s son, William, as a child. This image is referred to in a letter written by Maria Windeyer in November 1840: ’I’m going to send my dear Father a little packet containing Willy’s picture … we think it very like him … but the difficulty of getting him to sit still made the mouth less like his it does not convey to you the loveliness of his general look and is done on ivory and will therefore I hope keep well.’

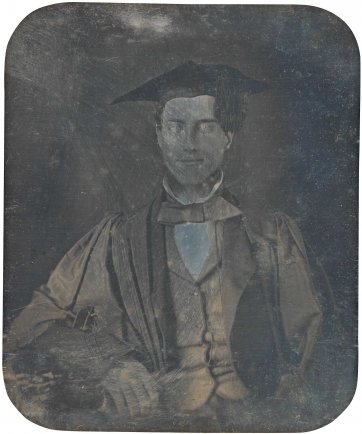

Sir William Windeyer’s is a lengthy and distinguished catalogue of achievements: King’s School-educated; one of the first to graduate from the University of Sydney and, later in life, its vice-chancellor, chancellor and a member of its senate; a distinguished barrister and Supreme Court judge; mentored in politics by Sir Henry Parkes and three times serving as a member of parliament; and a long-time supporter of charities and social issues. William was only thirteen when his father’s death left his mother with considerable debts owing on the family estate. Maria Windeyer’s remarkable accomplishment in retaining Tomago – through her own enterprise and with the assistance of friends – came to play a formative part in the public life of her only child, a public life seemingly infused with attitudes to women that were uncommonly progressive for a nineteenth century man. The influence of Maria and that of William’s equally strong-willed wife, Mary – who, after raising nine children, established her own profile as a suffragette, philanthropist, and campaigner for women’s education and employment – was expressed in William’s judicial compassion for female victims of male violence, his reform of divorce laws, and in legislation such as the Married Women’s Property Act, passed in 1879. His respect for women, however, was also sometimes the basis for controversy and accusations of bias or paternalism. ‘No one ever hesitated to credit Judge Windeyer with a sound knowledge of the law, with strong good sense, with masculine decision and self-confidence’, according to one obituary, ‘but his management of the divorce and criminal issues entrusted to him may be said to have sometimes provoked criticism’ – remarks referring to decisions made by Windeyer in cases such as that of the ‘Mount Rennie outrage’, wherein he sentenced four youths to hang for their part in the gang rape of a teenaged girl in Sydney in 1886.

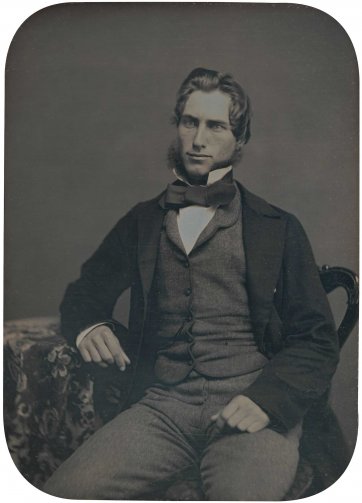

One can look to formal, public portraits to locate something of that ‘masculine decision’, sternness eminence, and authoritative physical presence. Tom Roberts’s 1892 portrait of the recently-knighted judge – also gifted to the Gallery by William’s great-grandchildren in 2009 – for example, places him as the third in a trio of paintings referred to by Roberts as ‘Church, State and the Law’ (the other two subjects being Parkes and Cardinal Patrick Moran). But it is in the small portraits never intended for public view that his eminence is prefigured, and more specifically, where one can discern something of the strong sense of public duty that emerged from William’s private experience and circumstances, and the models set for him by his family. His radicalism was firmly based in traditional beliefs about morality, religion, and chivalry, and in ideas about the social responsibilities of gentlemen – and gentlewomen – in tempering society’s vulgarities. The distinguished features of William in his twenties, newly married and admitted as a barrister, are preserved in an exceptionally fine daguerreotype of the 1850s, a powerful image that suggests something of the private side of his personality and awareness of himself as someone marked for distinction. You can’t help but admire the cut of his jib. The starchiness of his collar, confidence of his tailored suit, and the watch chain trailing from his waistcoat button. The assured but insouciant pose. The smooth-skinned hands of an educated man and a handsome face clean-shaven but for those extraordinary sideburns.

For the National Portrait Gallery to present a narrative of the history of portraiture, such objects as these are crucial. Until recently, the Gallery had only one daguerreotype in its collection and but two miniatures. This group of works are thus very pleasing additions: beautiful objects of impeccable provenance and of equally impeccable subjects which, even more appealingly, form a beguiling document of the practice of private portraiture in nineteenth century Australia.