Jessie Street was as young as six when she first decided she’d drawn a short straw by being born female. Around the age of ten she started praying to be turned into a boy and, when thwarted by the failure of her petitions, resolved instead never to let gender get in the way of her ambitions.

True to form, by the end of her eight-decadelong life, Jessie Street had amassed a daunting and exceptional catalogue of achievements in the sphere of women’s rights and in other defining social issues of the twentieth century.

Jessie Street (1889–1970) was born in India where her English father, Charles Lillingston, worked in the Civil Service. Her mother Mabel was one of eight daughters of Edward Ogilvie, the owner of a pastoral estate called Yulgilbar on the Clarence River in northern New South Wales. With this pedigree, it was inevitable that Jessie would be raised to, as she put it, ‘behave like a little lady’. Growing up in India, she formed (forbidden) friendships with the household’s Indian staff which, as explained in her 1966 autobiography Truth or Repose, enabled Street to develop an awareness of the unjustness and irrationality of prejudice. Hence her early understanding of the basis of discrimination against women: ‘As a child, I felt I had superior intelligence to a lot of boys … and nothing used to infuriate me more than to feel I was being treated differently, and didn’t have the same rights and opportunities as my brother.’ Following her grandfather’s death in 1896, Jessie came with her family to Australia to take up residence on the station her mother had – in a progressive twist for a landed family – inherited ahead of two brothers. Jessie Street never knew her maternal grandparents, yet their stories – and Edward Ogilvie’s legacy in the form of Yulgilbar – nevertheless served to beef-up the already feisty convictions she’d formed as a little girl.

Edward Ogilvie (1814–1896) was a typical squatter: a hardworking, determined man who fashioned empire and wealth from commonplace colonial beginnings. Ogilvie took up land at Yulgilbar in 1840 and within ten years had developed it into 200 000 hectares of prosperous sheep and cattle country. By various accounts a rigid, overbearing and quarrelsome man, Ogilvie was also said to be generous and fair to his workers and to Yulgilbar’s Aboriginal people. His granddaughter, however, would come to consider him as ‘hard-hearted’ for what seemed to her his perfunctory approach to marriage, courting and acquiring his first wife, Theodosia, amidst an extended period of travel and livestock-buying in Europe. The daughter of a Dublin clergyman, Theodosia Ogilvie (1838– 1886), was a woman in possession of most traits deemed desirable in nineteenth century wives: ‘pretty, with easy and elegant manners, very natural and unaffected’, and with a delicate constitution. Theodosia was nineteen, more than twenty years Ogilvie’s junior, when the pair were married in September 1858.

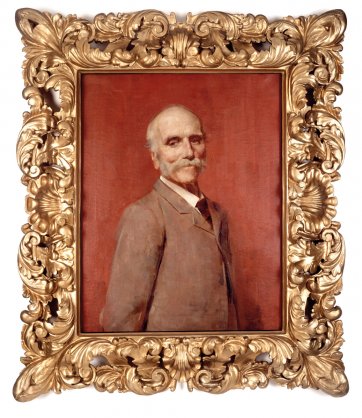

Theodosia sat for a portrait in the course of her Italian honeymoon, the unknown artist snaring in pastels the fair-skinned beauty held to have smitten Ogilvie on first sight. Much taken with an idea of himself as the founder of a pastoral dynasty, Ogilvie later included Theodosia’s portrait in a mini-gallery of family likenesses displayed in Yulgilbar’s baronial, faux-Florentine ‘Big House’, designed by Ogilvie and completed in 1866. Eventually displayed here also was Tom Roberts’s fine and striking portrait of Ogilvie himself, painted around 1895 while Roberts toured northern New South Wales in search of Aboriginal subjects. Roberts considered his painting of Ogilive ‘an opus’, the bold background colour and forthright composition suggesting the swagger and pride of the painting’s strong-willed subject.

Theodosia’s portrait arrests in a different manner with a direct but pensive gaze. Within a year of her portrait being painted, Theodosia was living on her husband’s Australian property and anticipating the first of the confinements that continued almost annually throughout the 1860s. A broken hip suffered during the birth, in 1877, of her eleventh child – a son, who survived a little over a fortnight – meant that Theodosia spent the remaining years of her life unable to walk. She died, aged forty-seven, in 1886. This sobering history aside, Theodosia’s marriage was a happy one lived in fine fashion. Yet, in an interview recorded in 1967, Jessie Street would cite the ‘limited existences’ of women like her grandmother as a spur ‘to do what I could to improve women’s status and conditions’.

For Street, life on a cattle station allowed deviation from the ‘little lady’ norm, but her tomboyish nature was tempered by the narrow education meted out by governesses. ‘After all, I was a girl. Any innate gifts or potentialities I might have had were of no importance – all society expected of me was that I should know how to dress and behave and, when the time came, marry a suitable husband. I was supremely indifferent to these prospects’. Luckily for her, the affects of such an education unravelled when, on the family’s return to England in 1906, Jessie was enrolled in a progressive girls’ school, Wycombe Abbey, where students were prepared for university and encouraged to take an interest in world affairs. Street came back to Australia determined to study, irrespective of her father’s conviction that university would lead only to her meeting and marrying a ‘bounder’. Her father’s objections overcome, Street enrolled at Sydney University in 1908, her three years there resulting in her first excursions into women’s campaigns and a secret engagement to law student Kenneth (later Sir Kenneth) Street.

From here on, her political activity snowballed. Holidaying in England in 1911, Street joined in on suffragette demonstrations. She ran her own dairying business at Yulgilbar before returning to Europe again in 1914, stopping at an international women’s conference on the way and arriving in London just before the outbreak of war. Refused war work as a driver on the basis of her sex, she went to New York and worked at a reception centre for young girls accused of prostitution. Back in Sydney in 1916, she co-founded an organisation advocating sex education and over the next decades mixed her work for women’s organisations (on issues including birth control and equal pay) with the running of an employment agency and relief work during the Depression. Later, she became the only Australian woman delegate to the founding of the United Nations and was a player in the formation of its Commission on the Status of Women. She became the target of surveillance (and spent a period of time away from Australia) for her support of trade and cultural relationships with the Soviet Union.

She worked on the executive of the World Peace Council and late in her career successfully instigated the 1967 referendum on Aboriginal rights. By the early 1930s, Jessie Street was one of the country’s most prominent feminists as well as the mother of four children and wife of a Supreme Court judge. Later in her career – such as when she stood as a Labor candidate for the conservative seat of Wentworth – Street would be accused of betraying her class with her avowed socialist beliefs. Yet the line between her status and politics was by definition a fine one, remembering that some of the most effective early feminists were women who harnessed educations and financial independence to the achievement of decidedly radical ends.

This anomaly is tracked in images and descriptions of Street around this time. When it profiled her in the early 1930s, the oafish Smith’s Weekly was surprised to find neither a frumpy battleaxe nor a vacuous socialite, but ‘a youthful and kindly woman with an abundance of resolution’. Her place as both a public political figure and elegant ‘society’ wife is also reflected in photographs by Harold Cazneaux and Bernice Agar (both from the stable of artists featured in the über-stylish Home magazine), and also by Judith Fletcher, who by 1920 had made her name with studio portraits and fashion photography.

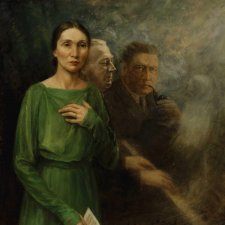

In Sydney from 1924, prolific portrait artist RH Jerrold Nathan (1899–1979), with his Royal Academy training, combated the perceived threat to art from modernism with accomplished, conventional works celebrating the status of the city’s pre-eminent families. Almost every Archibald Prize catalogue between 1926 and 1958 lists at least one entry from him, with businessmen, politicians, professors and judges (and the wives thereof) numbered among his many subjects. Jerrold Nathan’s portrait of Jessie Street was one of a pair he painted for the 1929 Archibald race – its companion a portrait of Linda Littlejohn, another feminist who with Street was co-founder that year of the United Associations of Women. There is a certain irony, perhaps, that Jerrold Nathan laid down the likenesses of women whose ideas were potentially as corrosive to the status quo as modern art was to realist traditions like portraiture: subjects like Millicent Preston Stanley (the first woman elected to the NSW Parliament); publisher Florence Taylor (the first Australian woman to qualify as an architect); and feminist Betty Archdale (the first to captain her country’s national women’s cricket team). His portrait of Street demonstrates his sometimes florid handling of paint and seeming fondness for depicting women in rich fabrics, furs and jewels, despite this subject’s being more commonly found in the no-nonsense combo of a suit, blouse and sensible shoes. But in her posture and firm gaze, Nathan has suggested Jessie Street’s warmth and her ability to warm others to the support of her many causes. It hints too at the resolve and resilience with which Street met the jealousies of rivals and the later, more determined and damaging attacks applied by governments or political parties suspicious of her beliefs.

Jerrold Nathan’s portrait of Jessie Street has remained in family hands since 1929 and has been, until recently, displayed at the Sydney library named in her honour. Tom Roberts’s portrait of her grandfather, in its elaborate hand-carved frame, has since 1972 been in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales. The loan of both paintings to the National Portrait Gallery during 2009 has enabled Jessie Street to take her place in proximity to her tough and uncompromising forebear, reminding us not only of her origins in an exceptional family, but also of the underpinnings of her fine, complex and distinguished life of action in the arena of women’s rights.