In its obituary for Vanity Fair editor Frank Crowninshield, the New York Times credited Crowninshield with developing ‘café society’ in America. Launched in 1913, Vanity Fair got off to a poor start but was rescued when Condé Nast appointed Frank Crowninshield editor from the fifth issue.

Crowninshield’s vision was simple, direct and effective: ‘the magazine should cover the things people talk about: parties, the arts, sports, theatre, humour, and so forth’. He lead the magazine until it ceased publication in 1936 but his philosophy was maintained when Vanity Fair reappeared in 1983 and has ensured its role as a cultural leader since. The exhibition of photographs that featured in Vanity Fair, now displayed at the National Portrait Gallery, celebrates the glamour and cosmopolitan style of one of the most famous magazines of the twentieth century.

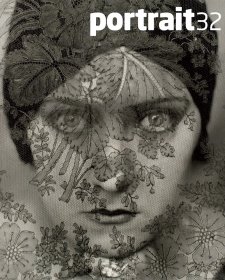

Vanity Fair Portraits: Photographs 1913-2008 draws on the visual archives of the journal, graphically illustrating Crowninshield’s international café society of glamorous and influential actors, writers, dancers, musicians, athletes, artists and poets. The exhibition of 150 classic images charts a history of photographic portraiture through the rich pages of Vanity Fair magazine. Canberra is the only Australian venue of this touring exhibition, originally developed by curator Terrance Pepper from the National Portrait Gallery, London and Vanity Fair’s Editor of Creative Development, David Friend.

In its first incarnation Vanity Fair brought together the most fashionable subjects, the most talked about writers and the best photographers. It seems almost astonishing that the likes of Dorothy Parker, HG Wells, James Joyce, Rebecca West and George Bernard Shaw should be contributing articles and that luminaries Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, Charlie Chaplin, Albert Einstein and Jean Harlow were pictured by the likes of legendary photographers Edward Steichen, Man Ray, Cecil Beaton and Baron De Meyer and George Hurrell in rare vintage prints. Along side these are more modern subjects Demi Moore, Arthur Miller and Madonna, as well as a significant number of famous Australians, taken by some of the world’s best photographers such as Annie Leibovitz, Helmut Newton and Mario Testino.

The contrast is illuminating and provides a fascinating insight into the technological and social changes that characterise the modern period. The photographic, printing and publication technologies mean that the earlier photographs are predominantly black and white gelatine silver prints, significantly smaller than the big colourful digital photographs that are produced today. The photographs record social mores that evidence the dramatic changes in our society. Consider the contrast between the suggestive eroticism of George Hurrell’s Jean Harlow, clad in her silken negligee and lolling on a smirking bearskin rug, against the unabashed full nudity of Keira Knightly and Scarlett Johansson as photographed by Leibovitz in 2005. And it would have been utterly unthinkable to have the naked and seven months pregnant Demi Moore (again photographed by Leibovitz) on the cover of any magazine before the 1991, and even then it aroused great controversy.

One of the first Australians to be associated with Vanity Fair was Anton Bruehl who was born in Port Augusta, trained as an electrician in Melbourne but found his vocation as a photographer in the United States. Bruehl learnt his trade with eminent pictorialist photographer Clarence White, but developed a crisp graphic style in contrast to his master. He was considered one of the most successful commercial photographers of the thirties and forties, working on commission for Vanity Fair many times, especially for his colour covers. His black and white portrait of Louis Armstrong is a fine example of his craft. Bruehl was also one of the pioneers of the commercial use of colour photography and a number of his full colour covers (colour was generally restricted to the cover) are displayed in the exhibition.

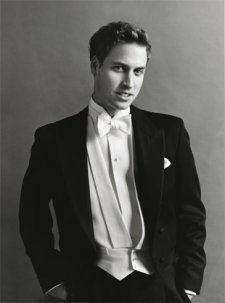

Bruce Weber’s smouldering portrait of Heath Ledger is a striking example of the contemporary portrait in its large scale and reliance on colour to enhance mood. The photograph was taken in 2000, soon after Ledger had achieved international stardom in the film, A Knight’s Tale. Sultry and raunchy, Ledger slouches as indolently as a street tough but the menace of the pose is undone by his magnetic smile that endearingly evokes the typical Australian ‘boy next door’. Ledger’s career reached its apogee with his role as the Joker in The Dark Knight. As the Joker, Ledger delivers a powerful account of character doomed to be Batman’s nemesis, a troubled and complex persona, haunted by personal demons. Ledger died in January 2008 while the film was still in the last stages of production. Released in July that year, the film broke box office records. Ledger’s tour de force performance as the Joker terrified movie-goers, earned him the admiration of his peers and the respect of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences who posthumously awarded Ledger an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. While the outstanding success and sheer conviction of Ledger’s performance in his last film role have coloured public perception of the actor, Weber’s full length portrait dissipates the brooding shadows of The Dark Knight and captures him at his best: sunny, funny and sexy.

Annie Leibovitz, a celebrity in her own right, has made portrait of several Australian sitters. She pictures media baron Rupert Murdoch as he captains his yacht into troubled waters, As in her portrait of Murdoch, Leibovitz pictures actress Cate Blanchett outside her professional role, sitting poolside, cigarette in hand and lost in thought. She captures Nicole Kidman’s ethereal beauty with equal simplicity.

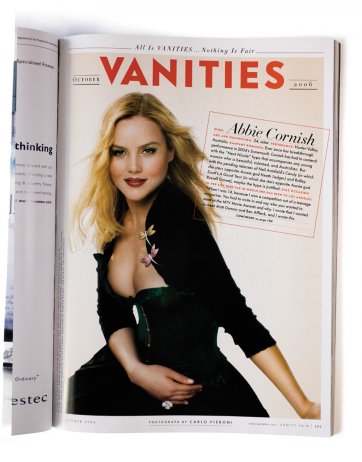

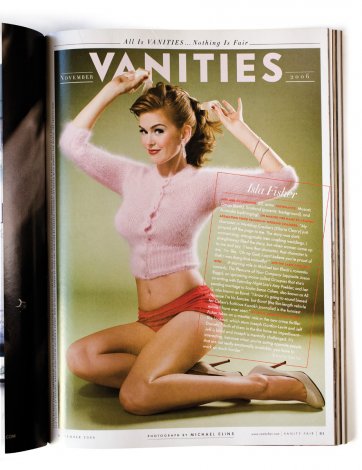

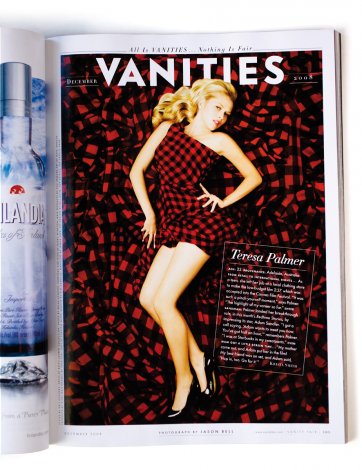

The striking portraits of Australians in Vanity Fair were commissioned for the publication and intended to be seen first and foremost in the pages of the journal rather than gallery wall. For this reason, a number of magazine ‘spreads’ are included in the exhibition, preserving the original display context. While linking the image to the journal, this economic means of display allows additional representation of Australians within the exhibition. Eric Bana, Abbie Cornish, Russell Crowe, Teresa Palmer, Rachael Taylor and Naomi Watts are also included in the Vanity Fair exhibition.