When news broke in early 2008 that Practising the Minuet: Miss Hilda Spong was coming up for sale amidst other works from the collection of the late Kevin ‘Pro’ Hart, National Portrait Gallery Director Andrew Sayers and Board Chair Marilyn Darling were immediately alive to the possibility of its being acquired for the National Portrait Gallery.

The question was whether the painting’s subject, a demure ingénue, would fit the criteria for inclusion in the collection of the Gallery. A little research, however, established that far from being the obscure, if engaging, subject of a painting distinguished primarily by its artist, Hilda Spong enjoyed broader public appreciation than Tom Roberts, at least in their respective lifetimes.

Hilda Spong (1875-1955) came with her family from England to Melbourne on the Austral in February 1888, a few months before her thirteenth birthday. Hilda’s father, Walter Brookes Spong, was a watercolourist who had exhibited at the Royal Academy and with the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours. He was also a scene painter, who had worked at the Theatre Royal in Bristol and at Drury Lane. He came to Victoria having been headhunted by the Brough and Boucicault Comedy Company, established in 1886 by Dion Boucicault Jnr and Robert Brough, a former D’Oyly Carte Opera Company member who had come to the city in 1885 to perform in Iolanthe and decided to stay.

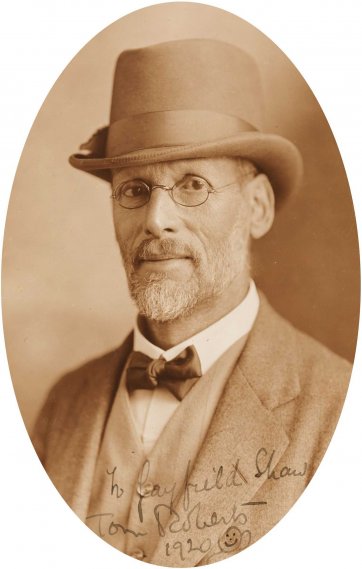

Tom Roberts (1856-1931) came to Australia from England in 1869, also aged thirteen. After working in a photography studio and undertaking some art training, he repatriated to study at the Royal Academy and travel in Europe. Returning in 1885, over the next few years he moved between Melbourne, where he established his studio, and Sydney. Once in Melbourne, Walter Spong fell in with Roberts and Arthur Streeton, joining them in the breakaway Australian Artists’ Society. For his part, Roberts lost no time in painting Hilda’s young mother, née Elizabeth Tweddell, for a head study that he exhibited in May 1888. All of them were in Melbourne for two events that rocked the Melbourne art and theatre set in mid-1889. In May, the Brough and Boucicault base, the Bijou Theatre in Bourke Street, burned down, with most of the company’s props and costumes going up in the blaze. Three months later, Roberts, Streeton, Charles Conder, Frederick McCubbin and a few other artists mounted the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition in Buxton’s Art Gallery in Swanston Street. Similar in sensibility to a show of James Whistler’s in London five years before, the exhibition of numerous tiny works was set off with richly coloured swagged and knotted silks, parasols, vases and arrangements of flowers and leaves, artfully disposed by Roberts. Now regarded as a watershed Australian show, it attracted jubilantly derisory reviews.

Between them, by the end of 1890 Roberts and Streeton had conjured up a fair number of the paintings that were to contribute significantly to Australia’s longstanding idea of itself, including Shearing the rams 1888-1890, The breakaway c.1890-1891, Golden summer, Eaglemont 1889 and Still glides the stream, and shall forever glide 1890. It seems extraordinary to contemporary readers that the creators of such ‘national icons’ would paint theatre scenery, but historian Anita Callaway explains that in the late nineteenth century artists had no qualms about transferring their efforts to a huge canvas exposed to broad popular view. For the opening of Melbourne’s new Bijou Theatre in 1890 Tom Roberts worked with Walter Spong on the ‘act drop’ that sat, during lulls in the action, within the frame of the proscenium arch like a giant painting. Few of these drops survived; although it cost a fortune, Roberts’s and Spong’s Comedy Banishing Melancholy drop, featuring figures by Roberts in front of a trompe l’oeil lace background handled by Spong, lasted only two years.

Julian Rossi Ashton, who was later to exert inexorable influence as an art teacher in Sydney, may have made his little picture of Hilda Spong on his visit to Melbourne in 1890, when he initiated the purchase of Streeton’s Still glides the stream for the National Art Gallery of New South Wales. Perhaps he had been captivated by her in Sydney the year before, where she had made her silent stage debut in the Brough and Boucicault Company’s production of Joseph’s Sweetheart at the Criterion Theatre.

After taking some acting lessons, Hilda Spong made her speaking debut in 1891 in the Brough and Boucicault production of Dr Bill. Theatre historian Elisabeth Kumm, who has generously shared her research-in-progress with the National Portrait Gallery, has tracked her rapid rise to the status of a favourite with theatregoers. Toward the end of her first year on stage, one of them made a ham fist of a poem in praise of her appearances at the new Bijou theatre in which ‘Hilda’ was unabashedly rhymed with ‘St Kilda’. At the end of 1891 she appeared in Bijou’s Christmas production of Much Ado About Nothing, for which not only Roberts but Streeton and Frederick McCubbin worked alongside Walter Spong to set the spectacular scene. According to art historian Geoffrey Smith, when Arthur Streeton visited Melbourne in 1891 he was so embarrassed for cash that he was ‘forced to paint novelty images on tambourines’ so doubtless he found the theatre work a welcome source of income. Perhaps, though, he was also happy enough to be involved in the production so that he could ogle a certain pretty cast member. The young Streeton seems to have had an eye for teenage girls; a letter he later wrote to ‘Bulldog’ Roberts from England described how one such, ‘almost sixteen, good looking girl (amorous type, Bulldog) swept up for me and whitewashed the hearth and got 2/-.’ In a letter to Roberts from Melbourne he described an ‘At Home’ he had attended:

I think the thing was a frost, but still there was afternoon tea and sponge cake, etc., and the people most interesting. I enjoyed it, rather.

‘May I bring you a cup of tea, Miss Spong?’ ‘Oh, thank you, Mr. Streeton.’ I cross to the teacups … Spong is a shallow, sceptical chap … After I had done my share I sloped away …

The same year he wrote to Roberts that he had been ‘down at Spong’s on Sunday evening … Miss S pouring out tea and looking very charming; she’s only a young maid, but seems to wish to appear older – a woman, an actress of experience … Yes, she looked very pretty.’ In another letter the same year he stated again that she ‘looked very fine and charming’.

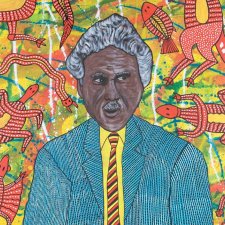

Hilda is thought to have persuaded Roberts to paint her in 1893. Helen Topliss writes that this portrait was ‘said to be commissioned’ by Hilda and given by her to Hessel Linsley, a friend of Roberts’s whose son, Rex, he had depicted a few years before. Although the golden girl seems to step before nothing but a suspended drop of drab fabric, close inspection reveals an austere persistence of Roberts’s Whistlerian props: the vertical brown slashes on the right are probably the ‘tall bullrushes and reeds [that] stood in an Ali Baba jar’ in his studio (seemingly the same dried stalks that appear in his portrait of Mrs Abrahams in 1888).

By 1893 Hilda was showing so much promise that Walter Spong established a company to highlight her talents. That year, Hilda had starred in As You Like It in Australia; Bert Lawson’s The Rosalind Waltz, prominently dedicated to her, was published with a photograph of her provocatively costumed as Rosalind’s male alter-ego, Ganymede, on the cover. The Howe-Spong Company having travelled to New Zealand, the Wanganui Herald reported in April 1894 that Hilda had gone down a treat in the Wellington season of the same play, reporting that

Miss Spong played the part prettily, and, for so very young an actress, cleverly. She had evidently given to it considerable study. She was letter perfect, and a feast to the artistic eye throughout. The production was splendidly set. Mr Spong’s scene in the Forest of Arden quite came up to expectations.

It was one of many such reviews. In the winter of 1896 Hilda left Australia to establish her career in London, making her Drury Lane debut in The Duchess of Coolgardie: A Romance of the Australian Gold Fields in September that year. Streeton left Australia for England in 1897, stopping in Cairo, where Spong joined him, paintbox at the ready. Writing from London in 1898 Streeton told Roberts that he had been to the Royal Academy show, in which Spong had two pictures:

Spong got his back up when I said that the ‘International’ Exhibition in Knightsbridge was finer as an art exhibition than the Academy; put it down to my not getting in … The English is not an artistic race; it is still too healthy and warlike … London is a bit trying at times.

Penning another letter in Chelsea on a Sunday morning, the church bells ringing, he describes the scene in his tiny flat: his ‘hell-hole’ fire, his books, and little pieces of art including ‘a good portrait of Miss Spong (now in America) unfinished – dashed in in one day.’

By January 1898 Hilda Spong was well established on the London stage. This is proved by an extraordinary piece of evidence, an oil portrait of her which could scarcely be more different from Roberts’s: Walter Sickert’s life-size representation of her in costume, The Pork Pie Hat: Hilda Spong in ‘Trelawny of the “Wells”’. Measuring more than two metres square, showing her in a commodious crinoline against a backdrop of patterned wallpaper, it was painted during a period of personal vicissitudes and – as his biographer Wendy Baron puts it - ‘wildly incongruous stylistic experiments’ for Sickert. The Pork Pie Hat was painted from a photograph commissioned purposely by Sickert, a theatre-lover who had been to see Trelawny of the ‘Wells’ with portraitist William Rothenstein. A contemporary review notes that the strange picture ‘occupies a self-defeating quantity of wall space’, admitting that it testifies to Sickert’s grasp of the principles of flat decoration but suggesting that it would have been better if smaller - ‘for subjects have their sizes’.

The irritatingly-titled Trelawny of the ‘Wells’ took Hilda Spong to America. The play opened on Broadway in the Lyceum Theatre in November 1898, with Hilda reprising her role as Imogen Parrott. A year later, she appeared as Mrs Onslow Bulmar in Wheels Within Wheels at the Madison Square Theatre. In this production, she was fortunate enough to catch the eye of America’s great portraitist William Merritt Chase. He painted her in the glitteringly beaded, velvet-caped costume she wore in the play, probably not on commission – although Hilda owned the portrait for a while – but more likely as an advertisement for his talent in full flush. At some point, the artist regained the work; Chase’s widow recalled in 1925 that the painting was one she and he ‘both loved’. Chase’s portrait of Spong was exhibited several times in 1901 and again in 1910. In the interim, The Pork Pie Hat was exhibited more than once; it was included, for example, in the Salon des Indépendents exhibition in 1903. A decade later, having been refused when offered as a gift to the Tate Gallery, the Sickert portrait was one of the early acquisitions of the Johannesburg Art Gallery. There it remains, comparatively inaccessible to researchers.

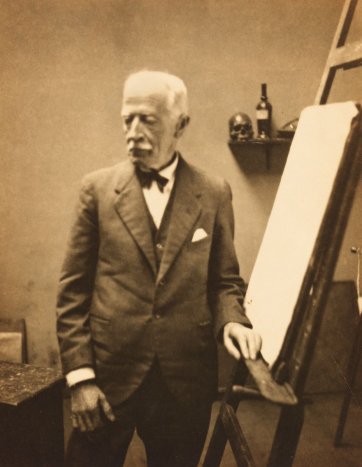

By 1903, Tom Roberts, too, had set off for England. He had persisted with his portrait work in Australia, including the series of ‘Familiar Faces and Figures’ that included Brough, Boucicault and the actor and impresario George Selth Coppin – the latter now owned by the National Portrait Gallery. He had painted Bailed up, In a corner of the Macintyre and a series of views of Sydney. Fatefully, too, he had secured the contract to paint the opening of the Commonwealth Parliament in Melbourne, which stipulated that he was to supply an ‘accurate likeness’ of no fewer than 250 of the people who were there on the day. It took him two and a half years to paint the 5 x 3m rendition of the Duke of York on the platform in the Exhibition Building, a shaft of Melbourne light slanting across the scene as he proclaims the Parliament open to the throng below.

At the age of forty-seven, Roberts hoped – perhaps assumed – that the ‘Big Picture’ would prove his breakthrough work in England, where he was to complete it. Having lugged it across the world, however, he found that

England doesn’t really want anybody. She has everybody and everything. The supply in is excess of the demand … everyone comes here sooner or later. The only thing is to make her want you, and that is difficult, for she really only wants the exceptional in any line.

In England, Roberts’s standing as a senior painter melted away, and the decade and a half he spent there, financially supported by his wife and wasting literally years on ill-conceived ventures, passed in a rarely-lifting fog of eye trouble, depression and rejection.

Like Kylie Minogue some ninety years later, Hilda Spong had arrived in England as no more than a colonial starlet, although its Daily Telegraph reported that ‘in Australia she is very much respected, appreciated and beloved’. It seems, however, that it had been relatively easy for her to make England want her. By 1903, she was well into her four decades of commuting between England and the USA to perform. Passenger records reveal, for example, that she arrived at Ellis Island on the Saint Louis from Southampton on 17 October 1903, and arrived again on the same boat nine months later. (From these same records, we know that up until 1923 at least, Hilda did not marry, for they baldly document the marital status, as well as the age and place of residence, of passengers.) As Christmas approached in 1904, Joseph Entangled came to Boston from successful seasons in London, New York and San Francisco. The newspaper reported that the company, which had stayed together throughout, was ‘headed by the beautiful Hilda Spong.’ In April 1905 Harper’s Weekly ran a large picture of her in the revival of Sherlock Holmes – a production that ran for about nine months of that year. In 1908 the San Francisco Call reported that ‘Hilda Spong, a distinguished actress well known to San Francisco theatregoers’ was leading a forthcoming bill ‘at the head of her company.’ In 1910 she espied the Statue of Liberty from the front once again, coming back from London on the Campania. After visiting Australia to perform under contract to JC Williamson before the First World War, she returned to America.

Photographs of Hilda Spong on the internet provide a textbook visual record of the unprecedented social changes that transpired during her lifetime. There is a palpable sense of burdens discarded as she changes out of tight sleeves and puffy bodices, crammed and piled hats, sweeping trains, hair pads and cinched, crystal-armoured evening gowns to end up in early Chanel-style jersey separates, with a no-nonsense wavy bob and a simple string of pearls. It is testament to both her personal ambition and the opportunities afforded by her times that the gawky coquette of Roberts’s painting was the star of a pioneering racy film, Divorced, filmed in New York and released in 1915. Having returned to the comedic stage for The Love Drive with Fred Niblo in 1917, she played the female lead in A Star Over Night, also filmed in New York and released in 1919.

During the First World War Roberts and Streeton both worked at the Third London General Hospital, Wandsworth, Roberts taking on a punishing load as an orderly. From 1919 onward, each shuttled back and forth between Australia, England and Europe for a few years before resettling here permanently, Roberts moving to Kallista in the Dandenongs in 1923. Continuing to exhibit, from that time on Roberts mostly painted landscapes and flower pieces. The day after he died, in September 1931, Streeton’s obituary for him was published in the Argus. In September 1923, a few months after Roberts retired to the Victorian bush, Hilda arrived at Ellis Island on the Celtic from Liverpool. Her place of residence was listed as New York City; her age was listed as ‘4 …’. That year, she made the first of her hundreds of performances in The Swan with Basil Rathbone; reviewing the show, Time magazine described her as a ‘capable veteran’. She last appeared on Broadway as Miss Whiffen in Higher and Higher when she was sixty-five.

From the period when their lives intersected in the explosive cultural environment of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ in the 1890s Spong and Roberts both lived through an extraordinary period of history. From the early 1930s, Tom Roberts’s Australian reputation escalated; long known as the ‘father of Australian landscape painting’, he is now also regarded as our most elegant portraitist. The name of Hilda Spong, however, has been unrecognised by all but a few theatre historians. The purchase of her portrait by the National Portrait Gallery will go some way toward bringing artist and sitter into balance for posterity.