The charm of the carte de visite appeals today as much as it did for the respectable and the not so souvenir seeker of nineteenth century Australia.

Two photographs recently acquired by the National Portrait Gallery demonstrate some of the characteristics of nineteenth-century photographic portraits that make them so intriguing for contemporary viewers.

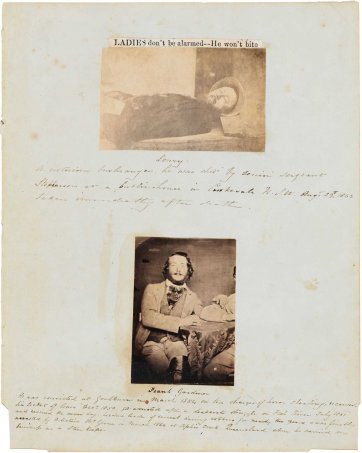

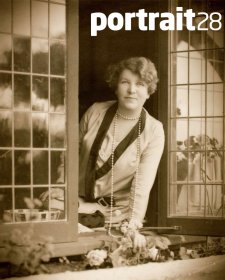

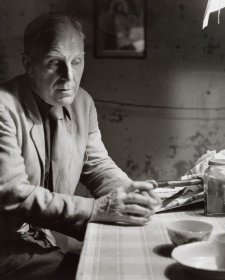

The first – a Freeman Brothers carte de visite of bushranger Frank Gardiner – bears all the hallmarks of a medium which created a revolution in the sphere of portraiture. Extraordinarily popular for their portability and affordability, cartes de visite democratised the art of portraiture by opening it up to all classes of society, respectable or otherwise. The second occupies the darker domain of the posthumous portrait and reveals the way in which photography – celebrated at its introduction as a more ‘truthful’ method of image making – was readily adaptable to the nineteenth-century pseudo-sciences of phrenology and physiognomy. Taken by an unknown photographer following Lowry’s death in 1863, this image of the cattle thief and bushranger Fred Lowry was, and is, a modest but significant example within the ‘trophy’ style posthumous portraits of Australian bushrangers. The preservation of these portraits of Gardiner and Lowry in a scrapbook compiled by an unknown woman also alludes to the easily, but willingly, scandalised sensibility of a society with a healthy appetite for souvenir images of well-known faces marked by beauty or freakishness, fame or infamy.

Frank Gardiner was born in Scotland in 1830 and came to New South Wales with his family as a child. By age twenty-nine he’d been jailed for horse theft, escaped, and been jailed again before turning to highway robbery in the districts around Cowra and Young. In 1861, having wounded a policeman in an altercation near Oberon, Gardiner moved to the Weddin Mountains, taking up with John Gilbert, Ben Hall and others to form a gang that in June 1862 pulled off the £14 000 Eugowra gold escort robbery. Gardiner’s growing notoriety was heightened by his ability to elude capture – he fled to Queensland with his mistress and remained there until eventually located by police and arrested in 1864. Gardiner was tried and found guilty on two non-capital charges and given a cumulative sentence of thirty-two years’ hard labour. His third stint in jail would also be cut short: in 1874, after considerable public petitioning, Governor Hercules Robinson decided that Gardiner had been harshly sentenced and released him, subject to his exile. Gardiner left Australia in 1875, ending up in San Francisco where he is said to have run a saloon. Varying reports have him meeting a suitably rough-and- tumble demise in a duel, a shoot-out, or a brawl over a poker game in Colorado around 1903.

A close reading of Gardiner’s portrait reveals much about both subject and medium and, in particular, about the era in which it was created. The development of cheaper, less cumbersome photographic processes in the late 1850s created great interest in portraiture, fed by the proliferation of photographic studios in the cities and photographers who took their studios to the bush. According to one report in the Argus in 1865, photographs were to be seen everywhere, ‘in every house and every tent’. The carte de visite – a small, calling-card sized photograph - was introduced to Australia in 1859 and taken to with relish. These cheap and mass-producible photographs were perfectly pitched to appeal to vanity and sentimentality, becoming a form of visual currency in a society keen to exhibit its middle-class credentials. Respectable rites of passage – a suitable engagement or marriage, births and families – were all commemorated with photographs which could be enclosed in a letter or displayed in an album made specifically for the purpose.

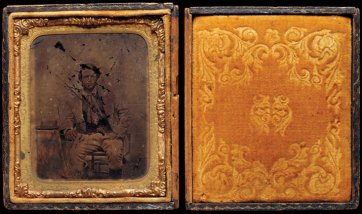

Yet it was a medium equally exploited by those with a taste for scandal or sensation. Cartes de visite were commonly taken to be sold to the subject and as such provided a unique means of gratifying one’s vanity. Frank Gardiner’s portrait suggests his own sense of his notoriety and bravado. He presents himself in the ‘flash’ attitude said to have been favoured by him and contemporaries like Gilbert and Hall - a cravat, waistcoat and thigh-high leather boots paired with a waxed moustache. One could be a criminal and a menace, but you could still have your portrait taken as if you were perfectly respectable, with the cheap and accessible forms of photography lending themselves to the easily blurred boundaries between good and bad, rich and poor, hero and villain. Gardiner’s portrait was the basis for an engraving published in the Australian News for home readers around the time of Gardiner’s trial in 1864. It bears a similarity to an ambrotype photograph of Ben Hall, now in the collection of the Justice & Police Museum in Sydney. Displaying many of the conventions of studio photography of the era, Hall is photographed in the clothes of a grazier, seated and leaning against a small table, often provided by the studio to aid stability during the lengthy exposure time. Hall is believed to have sat for this portrait, perhaps taken by a travelling photographer or regional studio, around 1861. Like many portraits of its type, it is contained in a hinged, velvet-lined case, able to be cherished, carried in a coat pocket or displayed on a bedside table, and is fascinating for its balancing of sentiment and performance. These portraits of Hall and Gardiner also correspond with myths current at the time about their raffish charm or bravery - myths which persisted despite their violent exploits.

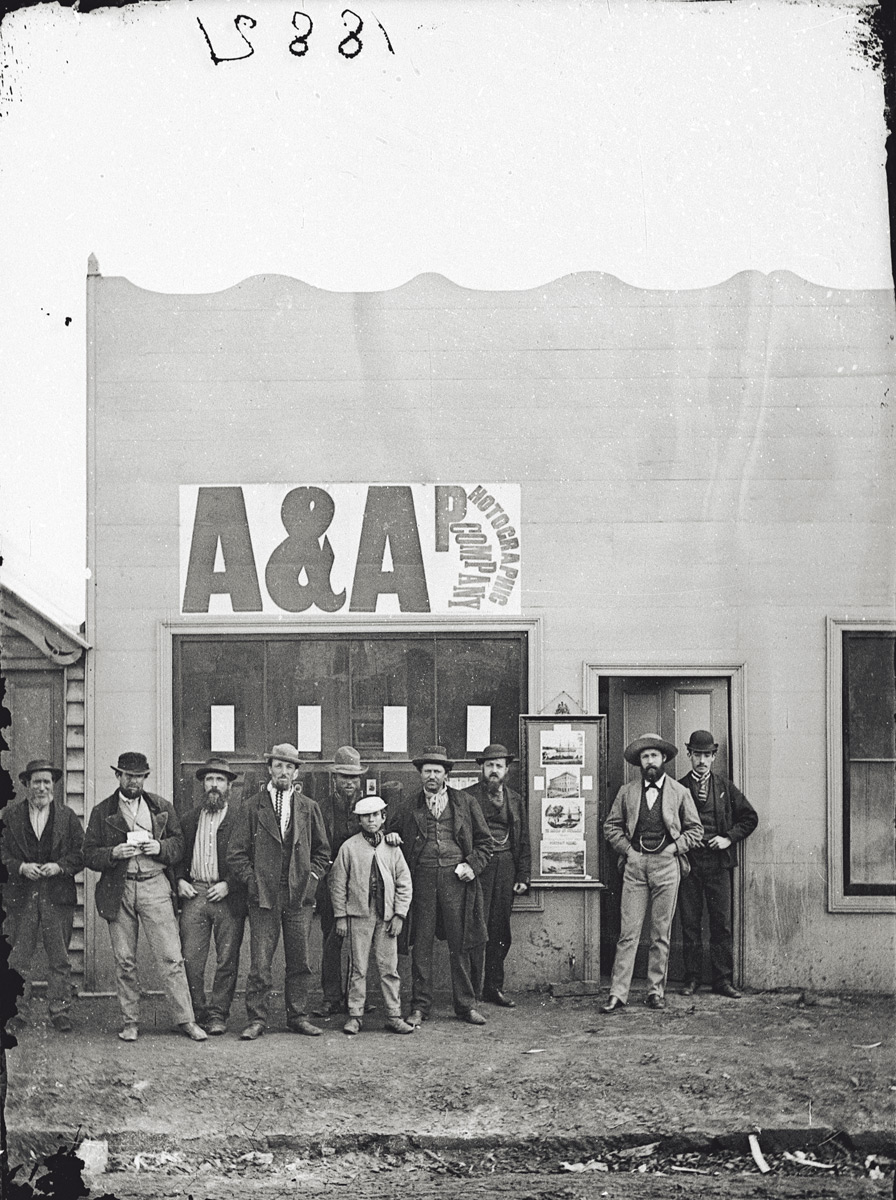

In contrast, Fred Lowry was not a bushranger celebrated for his looks or wit and, accordingly, the posthumous image of him exhibits an alternative side of the relationship between photography and power. Fred Lowry, born in 1836, was a stockman before taking to cattle and horse duffing. Throughout 1862 and 1863, Lowry was involved in shootings, an escape from custody, and thefts, including the bail-up of the Mudgee Mail in 1863. In August 1863 Lowry was holed up at a hotel about fifty miles from Goulburn. Tipped off, local police arrived and engaged Lowry and his companion in a gun battle during which Lowry was wounded. Loaded onto a dray bound for Goulburn, he died on the journey, but not before reportedly asking that it be noted that he ‘died game’. This photograph of Lowry’s body is among a number of posthumous portraits of bushrangers taken as evidence that the forces of law had finally triumphed over lawlessness, and peddled as proof of a criminal ‘captured’ – both in the literal and photographic sense. Other portraits within this small, brutal tradition include those of Frederick Ward, aka ‘Thunderbolt’, shot by a police officer near Uralla in 1870, and Daniel ‘Mad Dan’ Morgan, shot and killed during a hold up at a homestead near Wangaratta in 1865. The image of Thunderbolt shows the fatal bullet wound and the crude suturing of the incision made at his autopsy, while the images of Morgan after death parody his fierce reputation - propped up against a mattress, a revolver wedged into his hand, with one of his captors kneeling beside the body as if by a prize piece of game. Tellingly, images of both men were later reproduced as cartes de visite for anyone desiring such a souvenir. Perhaps the most famous example in the sphere of posthumous bushranger portraits is J.W. Lindt’s image of Kelly gang member Joe Byrne, whose body was displayed outside Benalla police station shortly after his death in the Glenrowan siege in June 1880. Artist Julian Ashton, visible at the far left hand side of the image, described the occasion in a memoir published in 1941. According to Ashton, photographers persuaded the police to hang Byrne’s body against an exterior wall using a pulley so that they might get ‘photographic records’. Ashton had earlier made his own record when he sketched Byrne’s body while it was laid out in a cell. Such portraits present a curious inversion of the nineteenth-century experience of death and mourning, which was generally confined to the private sphere. For certain people on the wrong side of the law death was turned into an undignified, unsentimental public spectacle – something which may explain why a number of examples of posthumous bushranger portraits have survived in public collections.

Cattle duffing, armed robbery, attempted murder and menace aren’t typically thought of as the sort of achievements that earn someone a place in a National Portrait Gallery, but these images were central to emerging myths about figures who continue to populate the Australian imagination. While modest in scale, they relate important stories about the attitudes and character of the society which created them and are an important addition to the Gallery’s collection of images of nineteenth-century Australia.