He sailed with his older brother, James. By the time their father, Alexander, came to the colony in 1824 with three daughters and two younger sons, James was engaged as a surveyor with Governor Brisbane in New South Wales, and William was in the Colonial Marine in command of the brig Cyprus, a government vessel trading between Sydney and Hobart Town.

Thomas Lempriere (1796–1852), too, came to Van Diemen’s Land, sailing on the Regalia in 1822. Marrying in 1823, he obtained a land grant and became a founding shareholder of the Bank of Van Diemen’s Land. After a brief foray into business with his father – who, like Kinghorne’s, emigrated only after his son had tested the waters – he became a Commissariat Department storekeeper at Maria Island and Macquarie Harbour. In 1831 he moved to Hobart to work as a clerk; by 1846 he was appointed a coroner. Four years later, his career was to end in Hong Kong, where he served briefly as assistant commissary-general.

For much of Kinghorne’s Vandemonian sojourn the colony was administered by Sir George Arthur, who presided, according to Robert Hughes, over the ‘closest thing to a totalitarian society … that would ever exist within the British Empire’. Manoeuvering ships laden with convicts, supplies and equipment between the raw new penal settlements of Van Diemen’s Land was not without hazard. In 1829, convicts aboard the Cyprusmutinied, making successfully for China, but Kinghorne was lucky enough not have been aboard. In 1836 Port Officer Moriarty testified that the duties on which Kinghorne was employed ‘were of a very arduous nature keeping up the communication with the penal settlements of the colony and conveying convicts to and from them more particularly Macquarie Harbour’, but he attested to the Captain’s having discharged his duties ‘with carefulness and fidelity’ and his having displayed ‘for the whole period an unvarying character for intelligence and zeal’. After more than fourteen years on the water Kinghorne made for dry land, receiving a grant of 500 acres at Bruny Island – probably in lieu of the pension for which he had applied – in November 1836. By that time, the dispossessed Indigenous people of the region were dead or had been herded to Flinders Island from one of the missions that George Robinson set up between 1830 and 1835. By the time Kinghorne’s portrait was made, it is estimated that there were fewer than twenty Aboriginal people left alive on the Tasmanian mainland.

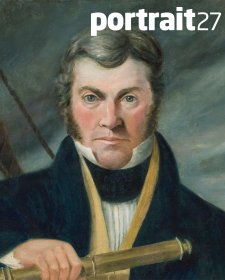

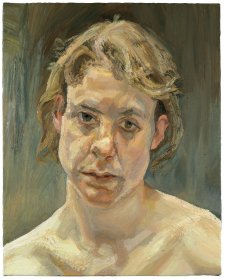

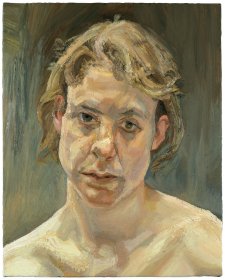

Besides his duties as a clerk, and as a father of twelve, Lempriere was an enthusiastic amateur painter. He made a number of portraits and other artworks, such as firescreens and ‘transparencies’– paintings on glass – during his time in Tasmania. Scenes that he recorded of convict life, The Penal Settlements of Van Diemen’s Land, were published in the Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science in the 1840s. From Lempriere’s diary we know that he and Kinghorne, his exact contemporary, were on friendly terms and dined together from time to time. Kinghorne sat for the artist several times in March and April 1834 – the year that the New Wharf, fronting present-day Salamanca Place, was completed and Port Puer, a prison for ‘depraved little felons’ aged nine and upwards, was established at Port Arthur. According to maritime authority Michael Nash, Kinghorne made seven return trips from Hobart to Port Arthur in command of the Isabella in the autumn of 1834, during the weeks in which Lempriere was working not only on his portrait but on a transparency for his ship’s cabin. Kinghorne made Lempriere a present of a flute in May. When he boarded the Isabella on 8 June 1834, Kinghorne took with him this portrait, inscribed ‘Capt. W. Kinghorne Commanding HM Capt. Brig Isabella painted by TJ Lempriere Commissariat Dept & presented by him to his friend Capt. K. as a small token of regard’.

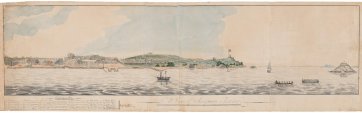

The period in which Kinghorne was in Van Diemen’s Land, plying the waters between the mainland and the penal islands in the Cyprus, Prince Leopold and Isabella, coincided with the peak years for whaling in the colony. The first sod turned at Risdon Cove in 1803 was still damp when the first whales were boiled down. In the early years of European settlement, the beasts were so numerous in the Derwent River that the racket they made is said to have kept people awake. The Derwent Whaling Club was founded in 1826. By 1830, when the brig Isabella was constructed at Sarah Island, the grisly industry was flourishing and the New Wharf was no sooner completed than it became a stinking hub for whaling boats, their crews and cargo. Shore whaling peaked in the colony around 1839 but it was played out by 1850, with the whalers forced into pelagic operations by the decimation of the southern rightwhale – which offered the promise of oil for street lighting, and baleen for corset stays – that swam close to shore.

Over the course of a season, southern right whales migrate from the coasts of South Australia, Victoria and eastern Tasmania up the coast of New South Wales as far as Jervis Bay and back again. At Jervis Bay, members of the Kinghorne family had established a property they called Mount Jervis. Probably toward the end of the 1830s, Captain Kinghorne established a whaling station at nearby Cabbage Tree Point to exploit the resources that gambolled in the bay. The establishment was fully operational by 1841; at that time, advertisements for land for sale at Jervis Town referred to ‘CaptainKinghorne’s whaling station’ to indicate the location of land parcels on offer. Michael Nash estimates that in the four years between 1835 and 1839 about 12 000 right whales were killed in Australian waters, but Kinghorne’s contribution to this tally is unknown. Whaling in Jervis Bay was to continue almost up to World War I.

Soon after he arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1824, Captain Kinghorne’s father Alexander, a civil engineer, was appointed superintendent of the convict farm at Emu Plains and relocated to New South Wales. In early 1826 William’s brother James succeeded their father as superintendent, although he, in turn, had been relieved of the post by 1829. By 1828 Alexander had become a magistrate, living in Liverpool. Another son, Kenneth, took on the running of their property, Cardross, in the Wollondilly district near Goulburn, and another, Alexander, established a series of flour mills. In 1834 the younger Alexander was living with his wife Jane Lambert at Rainville, near Bathurst. Between the 1820s and the 1840s the family also acquired land around Boorowa, as well as at Jervis Bay. Scattered as they were around New South Wales, the Kinghornes were severely affected by the drought of the 1840s. The senior Alexander went home to Scotland, where his wife, William’s mother Betty Brockie, had remained. He seems to have taken a different portrait of William with him, for in 1873 the Captain received a letterfrom Edinburgh, assuring him that ‘many a time when we looked at your portrait we spoke about you’. William’s generation persisted on the land, including his sister Elizabeth Chisholm, who had taken up acres adjoining Cardross, naming the property Kippilaw. By 1870, it seems that Captain Kinghorne was running a property named Saltwater Creek in the Shoalhaven area. As time wore on, generations of Kinghornes intermarried with other prosperous and prominent pastoral families.

Some of what we now know of Kinghorne is drawn from the papers of Miriam Chisholm, a twentieth-century descendant of William’s sister Elizabeth who lived at Kippilaw for most of her life. These papers, in chilly genealogicalparlance, note that the Captain ‘died without issue’. Hence, a note on the back of the portrait, postdating the artist’s inscription, indicates the status of the work as an anomalous family artifact in need of explication: ‘Great Granny Chisholm’s brother./Mother’s Mother’s Uncle./He’s Uncle Alec’s Uncle too/His father was/old Alec Kinghorne/who lived near Sir/ Walter Scott.’

Captain Kinghorne lived into his eighties. He is buried in the cemetery of St James’s Anglican Church, Kippilaw, amongst a host of Chisholms and a few Kinghornes. Kinghorne Street, one of the main streets of Nowra, is named after the family, as are Kinghorn Point [sic] between Culburra and Currarong and Kinghorne Street in North Goulburn.

The portrait of Kinghorne was offered for sale to the National Portrait Gallery by a further descendant of Elizabeth Chisholm. Director Andrew Sayers and Gallery staff drove deep into rural New South Wales to inspect the painting. Over lunch, our hostess hinted at the tone of the work, recalling that it had once hung near the bedroom but disconcerted by the Captain’s penetrating stare, she had encouraged its removal to the property’s original homestead. In due course the National Portrait Gallery contingent accompanied the owners through paddocks of frisking foals to the old slab house crammed with several generations’ worth of furniture, crockery and pictures. Here, brushing away spiders and wasps, Sayers took his first electrifying look at theportrait, glaring through the gloom. The painting was brought immediately for inspection to Canberra, where the valuer found the work ‘a very striking and appealing portrait’ with its rich and lively palette of blue and gold. Rare and valuable, the portrait of Kinghorne required restoration, which has now been carried out to sensational effect. When it is hung amongst the Colonial portraits in the new National Portrait Gallery late in 2008 – making, it is anticipated, a compelling centerpiece of the display – the portrait of Captain Kinghorne will make its first-ever public appearance, nearly 175 years after it was painted in an Australia so different as to be scarcely imaginable.