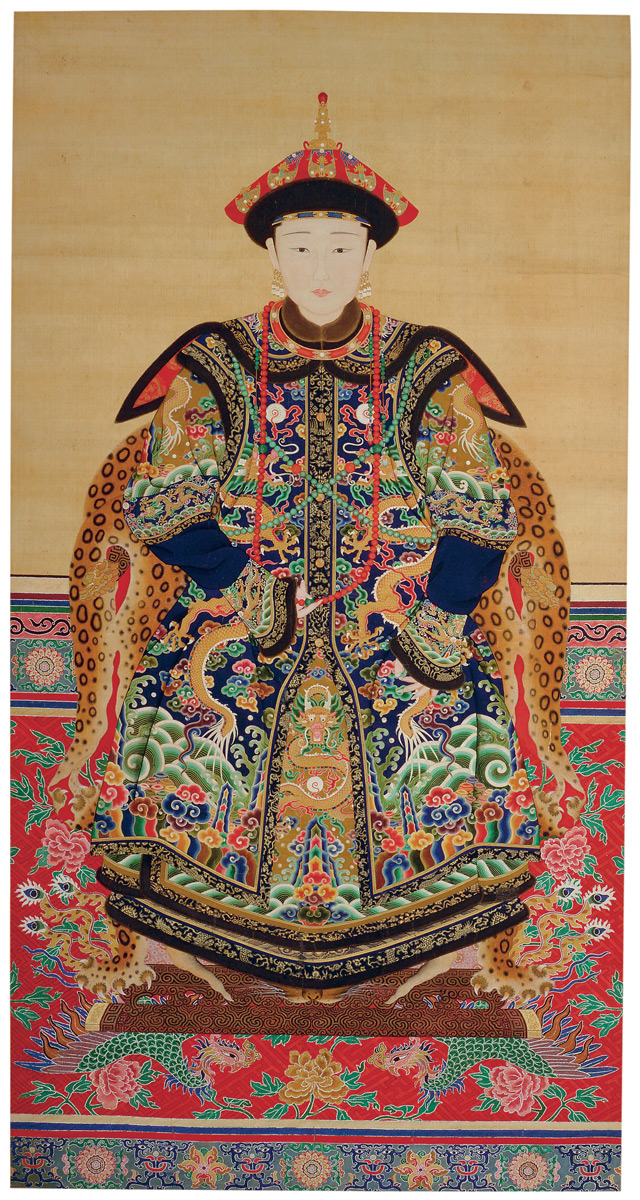

In Asia, artists created portraits to proclaim power or status, to remember the dead or their achievements, to recall the beloved, and to strengthen bonds between friends. These portraits triggered personal memories, inspired respect or awe, satisfied the thirst for knowledge, or enabled contact between human and divine realms. Today, they connect us to distant lives and offer insight into Asian cultures and values.

Facing East, an exhibition at the Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington DC showcases the art of portraiture in Asia over two thousand years

From the sculpted head of an Egyptian pharoah to contemporary photographs of Korean students, the portraits convey the distinct conceptions of the self that emerged in specific artistic, cultural, goegraphic, and historical circumstances. While each portrait is unique, together they reveal that the aspiration to record and remember individual lives transcends time and place.

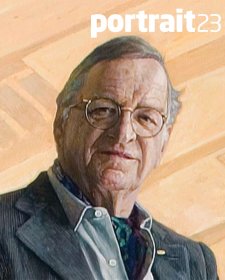

Likeness and Identity

How do we know when an image depicts a specific person? Likeness – the resemblance of a portrait to its subject – differs across cultures and over time. Likeness is so powerful that portraits often give the impression of a direct encounter between artist and subject. Many portraits, however, are based on memory or verbal descriptions. Yet even purely imaginary works can attain the authority of portraits drawn from life after they have been viewed or copied over the course of centuries.

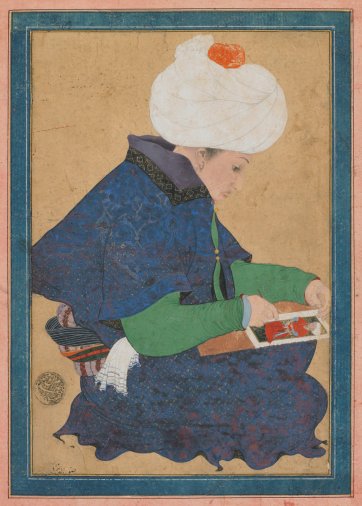

Portraits go beyond physical appearance. Some idealize features to suggest an unblemished character; others exaggerate physical details to identify the subject clearly. Much of the meaning in Asian portraits is communicated indirectly – through posture, gesture, setting, and costume. Some of the symbols in these portraits, such as halos and crowns, have familiar meanings that we can interpret easily. Others, such as the link between the profile and worldly power employed in Mughal portraits and American coins call for specific cultural knowledge. The choices that artists make to achieve likeness usually reflect cultural values. When artists redifine likeness by introducing new visual conventions into portraiture, they may be signaling a shift in culural perceptions about social roles or personal identity.

Portraits and Memory

Portraits have the power to evoke a person’s presence in the viewer’s mind. They draw close those who are distant, bring the past into the present, and even bestow life upon the departed. They are thus intimately associated with memory.

A portrait connected with death and burial can substitute in ritual for the person depicted, or it can offer the viewer imaginary but emotionally powerful and seemingly magical access to the departed. Indeed, the earliest portraits were probably those relating to death rituals, which were thought to forge a bond across time and space and between the living and the dead.

Projecting Identity

How would you fashion your portrait for posterity? Which aspect of your complex self would you represent? Would you choose a medium that could disseminate your image widely or would you restrict the viewing of your portrait to friends and family?

Before photography made portraiture broadly accessible and relatively spontaneous, artist, patron, and subjects made careful choices about the persona that a portrait would project. Many portraits incorporate some degree of imaginative role-playing. Rulers typically commissioned images that announced authority or contributed to the consolidation of power. Other classes of people sought to project social values that garnered respect. Portraits tell us as much about cultural preferences as they do about a single person’s life or appearance.

Reprinted, with permission, from Asiatica.

© 2006, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution. All right reserved.