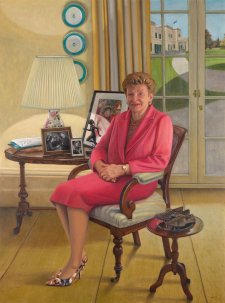

The National Portrait Gallery has a small collection of novel objects of portraiture, most of them representing Prime Ministers. A recent addition to this judicious group is a handsome commemorative jug representing Stanley Bruce, Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, Prime Minister from 1923 to 1929 and Australia’s High Commissioner in London from 1933 until the end of the war.

Stanley Melbourne Bruce (1883-1967) is one of only two or three Australian prime ministers born into a life of privilege. Growing up in St Kilda, Bruce attended Melbourne Grammar, where he captained football, cricket and rowing and was school captain in 1901. Continuing his education in England, he studied law at Cambridge, where he earned his rowing blue. Some years later, the Governor General, Lord Stonehaven, was to tell the Viceroy of India that Bruce struck him as ‘an outstanding example of what can be done by a combination of an Australian public school and a British University.’ Leaving Cambridge, Bruce remained in England to take care of the English end of his Melbourne family’s softgoods importing business, Paterson Laing and Bruce. He was called to the Middle Temple in 1907 and became chairman of the family firm the following year. During World War I he served with the Royal Fusiliers at Gallipoli, winning the Military Cross for his actions at Suvla Bay. Later he was awarded the Croix de Guerre avec palme. Invalided, he was still on crutches when he returned to Australia in 1917 and took over as general manager of Paterson Laing and Bruce.

Folklore has it that Bruce fell into Australian politics accidentally. In the memoir of Bruce that he wrote for the Royal Society, Robert Menzies wrote that he was elected ‘with no forethought or sedulous preparation, with no particular ambition’ on his own part. Heather Radi, however, in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, points out that he had political connections through his wife, Ethel, and he was not the political ingénue that history has painted him. Whatever his motives, his message was clear; portrayed in his electioneering pamphlets in his British Army uniform and pledging to ‘protect this country from the insidious doctrines of the disloyalist’, he was elected the Nationalist party member for the federal seat of Flinders in 1918. Remarkably, Bruce spent eight months of 1919 in London on his own business. His father had been a founder of Royal

Melbourne Golf Club in 1891, and Bruce himself was a lifelong enthusiast for the game. In early 1921, after another stint in London, he was golfing at the fashionable French resort of Le Touquet – where he often enjoyed a round with the Earl of Dudley and his second wife, the former Gertie Millar, lovely star of Our Miss Gibbs – when he learned that he had been appointed Australian delegate to the League of Nations in Geneva.

Bruce relinquished his own affairs when Billy Hughes, the Nationalist Prime Minister, offered him the post of Treasurer in late 1921. After the 1922 election Hughes was unable to secure the support of the Country Party, led by Earle Page, who held the balance of power. ‘Little Hughes’, as Bruce tended to refer to him, had no choice but to concede his leadership to the man Page would accept. Thus, aged only 39 and with only five years’ experience in party politics, Bruce became prime minister in February 1923. Finding himself ‘the Managing Director of Australia Limited (or unlimited)’, as Menzies put it, Bruce attempted to run the country along business lines, devoting much energy to strengthening trade with Britain. What he wanted from the old country was encapsulated in his policy of ‘Men, Money and Markets’: he encouraged British families to emigrate, while he secured loans from London financiers to fund infrastructure development and lobbied hard for preferential treatment for Australian goods in Britain. One of the great achievements of his prime ministership was to be the establishment of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, for which he brought in British experts to try to provide a scientific boost for Australian producers. Domestically, Bruce worked at maintaining the crucial Nationalist-Country party alliance, cooperating with Page in what was known as the Bruce-Page government. Page later wrote that he could recall ‘no heated or unfriendly exchanges’ in the whole of their association; ‘recriminations were unknown between us,’ he averred.

After the 1923 Imperial Conference Bruce appointed Richard Casey – like him, a product of Melbourne Grammar and Cambridge, a Gallipoli veteran and recipient of the MC – his liaison officer in London. Casey, who was to become Australia’s Governor General in 1965, sent very regular dispatches to Bruce with various enclosures. Often his letters took the form of numbered points, the diplomatic and political issues of the week taking precedence with points nine or ten, perhaps, containing amusing snippets of London life. In 1928 he related the ‘horrifying’ experience of seeing Bruce’s wax effigy in Madam

Tussaud’s, predicting that the ill-dressed mannequin would be mistaken for ‘a wide range of popular celebrities varying from Mussolini … to the late President of the Mexican Republic.’ The same year saw Casey planning to make a home movie of the British parliament in action: ‘The amateur cinematograph camera has become a practical machine for the ordinary person. I have one and find it most amusing. I propose to make a film, which I will call “Whitehall” … If you have any means of projecting such a film, I would send you out a copy if it turns out at all well.’ In the same letter, he related the farce that ensued when the King of Afghanistan visited Liverpool.

‘Chamberlain recently told the Cabinet [that the Liverpool City Fathers] sought to entertain Amanulla after dinner by some very expert conjurers they had got together … The first two tricks that were done before him, Amanulla got up and did rather better – rather to the conjurer’s discomfiture.’

Throughout Bruce’s time in office Casey acted as his man in London and major decisions were often taken on his advice.

In 1927 Bruce oversaw the move of Parliament to Canberra. His personal private secretary, golf champion and golf course designer Alex Russell, stayed in Victoria, but Bruce’s relocation provided him with an opportunity to emulate his father in becoming a founding member of the Royal Canberra Golf Club. He and Ethel were the first residents of The Lodge, negotiating its fit out with Melbourne decorator Ruth Lane Poole. Bruce opened the Sydney and Melbourne buildings in Civic at the end of 1927, laid the foundation stone of the Canberra Grammar School in 1928 and worshipped regularly at St John’s Reid. The Bruces’ visitors at the Lodge included the Duke and Duchess of York, here to open Old Parliament House, who gave Bruce a gold cigarette case engraved with their signatures. Another visitor was aviator Charles Kingsford Smith. Bruce knew something of flying, for in 1924 he had been the first Australian Prime Minister to travel by air on official business, travelling from Winton to Longreach with Hudson Fysh at the controls.

Bruce had always been concerned with wage costs. While acting as Attorney General in 1924-5 he had to contend with a vigorous waterside workers’ body. Though he was sympathetic to some of their claims he took measures to break a strike in 1925 and moved to deregister the Seamen’s Union. That year he comprehensively won the election, appealing for law and order and warning voters of the ‘wreckers who would plunge us into the chaos and misery of class war’. In 1927 he appears to have supported the formation of the ACTU – presumably because it was a move away from dealing individually with the state-based Trades and Labour Councils. As the 1928 election approached the government rushed through legislation to undermine the waterside workers’ union; although this was designed to reassure the electorate, Bruce’s reputation suffered when violent industrial action ensued.

In January 1929, Casey was writing to Bruce about scrapping Cypher B – ‘really no defence at all against anyone who wants to break it’ – for confidential messages between Canberra and Whitehall. Finishing with official business, he continued in a more personal vein: ‘I see that you have agreed to the Bruce Toby Jug being sold to the public. I inquired of the potters about it and got two of them. I think they have turned out very well indeed. If you want any I can get them and send them out.’ The jug to which he refers, the same that the National Portrait Gallery has recently acquired, was one of a series of four modelled by designer Percy Metcalf and produced between 1925 and 1928, around the same time that Metcalf designed the new Irish coinage. His other jugs depicted two British Prime Ministers, Baldwin and Lloyd George, and a British Attorney General, Lord Hailsham. Made at the Ashtead Pottery in Surrey, set up to afford employment to returned servicemen after the first world war, the jugs were issued in numbered limited editions – 1000 each for the prime ministers and 500 each for Hailsham and Bruce. The National Portrait Gallery’s example, spotted by the Director on a speculative visit to a travelling antique show, is number 1 of the rare Bruce jugs. Its provenance is unknown.

By March 1929, Casey was telling Bruce that ‘I am appalled at the problems that face you’. As the months ground on, Bruce was trying to look to economic expansion, but there were great tensions within his own party in which ‘little Hughes’ – whom he had repeatedly passed over for the ministry – was crucially involved. Robert Menzies recalled that ‘there could have been no greater contrast than there was between Hughes and Bruce; a contrast of minds, of background, of temperament, and, as I believe, of character.’ Hughes, said Menzies, ‘possessed a cruel and devastating wit, and recked little of other men’s feelings’. He had nursed his wrath since 1923, and was prepared to take his revenge when the time presented itself. Fearing worldwide recession, Bruce tried to cut wage costs by streamlining the industrial arbitration system, then split between the States and the Commonwealth. As the State premiers refused to refer power to the Commonwealth, Bruce effectively legislated to repeal the Commonwealth conciliation and arbitration laws. The Trades Unions were furious and many Nationalist and Country members were dismayed. Hughes – founder of the Australian Waterside Workers’ Federation – and five other members crossed the floor to vote against Bruce on the Maritime Industries Bill. Bruce lost his own blue-ribbon seat at the election in October 1929. Still the only prime minister to go that way, he was replaced by a Labor government led by James Scullin, to whom it immediately fell to deal with the Great Depression. Bruce’s Cambridge education, his commercial enterprises, his London legal practice and his wartime service had built him British contacts of tremendous value to Australia. In 1933, following Bruce’s re-election to the seat of Flinders, Joseph Lyons appointed him High Commissioner to London. The first Australian High Commissioner had been another former prime minister, George Reid, who was in London from 1910 to 1916 and saw the start of construction of Australia House; two more, Andrew Fisher and Joseph Cook, had followed him.

Bruce was to hold the High Commissioner’s position until 1945, lobbying for Australian producers, renegotiating Australia’s debt repayments, and advising the Australian government with regard to Commonwealth affairs. He had won a great deal of respect in the League of Nations, and presided over the Montreux Conference in 1936. Although he complained to Casey that some ‘evil chance’ had established his reputation as a professional chairman of international conferences and vowed to make an effort to dodge any ‘unpleasant and sticky’ jobs (indeed, he turned down an invitation to chair a commission on Palestine in 1936), his League of Nations contacts made it possible for him to be accepted – in a limited way – as an adviser to the British government as well as the Australian. In this capacity he played a key part in the abdication, telling Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin to inform the King that Australians would take a dim view of his marriage to Mrs Simpson. Notes reproduced in Cecil Edwards’s biography of Bruce show that he effectively coached Baldwin on how to handle the excruciating audience: ‘I said I would put it to him how I would see it if I were in his position … as PM I would feel it my duty to put the question straight up to the King …’ and so on, urging Baldwin to stipulate the consequences of marriage, abdication or a continued unofficial relationship in some detail.

Bruce always believed in prosperity as the best means of securing peace, and he chaired the League of Nations committee on world nutrition in the 1930s. As war loomed, perturbed by Churchill’s focus on annihilating Germany, he pressed for a stated aim of improving the world’s food and welfare situation. Seeing the coming conflict from both European and antipodean perspectives, he supported appeasement of Hitler and was particularly concerned about the absence of Australian policy on China. With the Japanese threat intensifying he tried to persuade the British to establish a naval base in Singapore and agreed with Menzies that Australian troops should not be committed to Europe while Japan was a threat to home. In the end, the troops were promised on Casey’s advice. Bruce resisted strong pressure from Page, Casey and others to return to Australia and contest the leadership after Lyons’s death in 1939. Remaining in London, he clashed many times with Churchill over Britain’s failure to inform its Dominions of its intentions, or consult their representatives on its international policies and actions. Although he was a member of the War Cabinet, having alienated Churchill he had little influence in it and was not always invited to its meetings or copied in to material circulated to its other members. Elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1944, Bruce retired as High Commissioner in August 1945 and came home. Colleagues again encouraged him to return to politics, but he declined, going back to London where he was a director of several companies and served on a number of London boards of Australian concerns. He was created Viscount Bruce of Melbourne in 1947, a year into his five-year stint as chairman of the World Food Council of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

In 1951 he accepted an invitation to become the first Chancellor of the Australian National University, whose Bruce Hall is named in his honour. He was Chancellor for ten years, visiting for ceremonial occasions, but he continued to live in London. In 1954 came one of his life’s sweetest rewards, the Captaincy of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrew’s. He is the only Australian to have held this honour, and for him it evidently counted more than being the first Australian to sit in the House of Lords.

Photographs amongst Bruce’s papers prove that he lived to enjoy a rowing event on Lake Burley Griffin, and he endowed the ANU in his will. Robert Menzies identified the development of Canberra, especially the creation of the lake, as one of the principal achievements of his own time as prime minister, and it must have satisfied him to write that Bruce wanted his remains in ‘the city whose beginnings he saw and whose progress he was able to appreciate’. Bruce’s ashes were scattered from a plane flying high over Canberra during his memorial service at All Saints’ Church, Ainslie, in March 1968. He is the only Australian prime minister whose remains lie in the city. Bruce’s papers, Casey’s letters and much personal memorabilia, including multifarious tokens of esteem, honorary doctorates and the coat and trousers he wore as the captain of St Andrews, are in the collection of the National Archives, a stone’s throw from Old Parliament House and just over the hill from the Lodge.