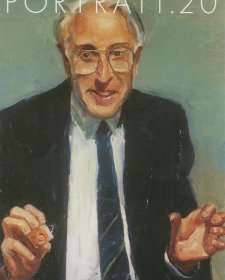

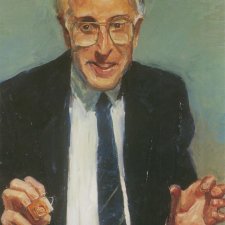

First I must ask what are painted portraits for? This question can best be framed with two quotations from different points in time. First, from British artist. Lucian Freud. 'I think a great portrait has to do with the way it is approached ... it is to do with the feeling of individuality, and the intensity of the regard and the focus on the specific'. Secondly, from historian and biographer, Thomas Carlyle, commenting in the 1840s,'... in all my historical investigations it has been one of the most primary wants to procure a bodily likeness of the personage enquired after... the Portrait was a small lighted candle by which Biographies could for the first time be read, and some human interpretation be made of them'.

Freud is taking a focused view about the particular character of a painted portrait; whereas Carlyle was referring to the use of painted portraits to help understand or define 'great men' and he was writing as photography was about to offer a new opportunity to record and circulate likenesses. Freud's comment was made in part to distinguish paintings from the mass circulation of photographic imagery. But for both of them the painted portrait speaks equally of authenticity and authority.

Portraits have a number of functions that go beyond the immediate purpose of recording a likeness. They denote status, power and wealth, convey the construction of dress and fashion and give insight to personality and psychology, taking account of the codes of public and private portraiture and the conventions of male and female portrayal.

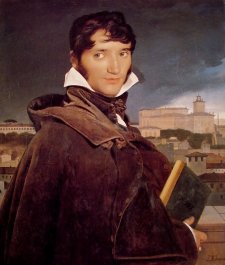

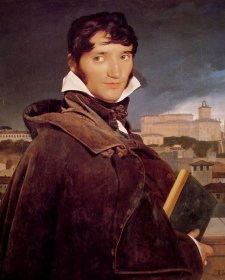

As the practice of portraiture developed in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, a number of strands emerged. A first strand is the 'State' portrait of which Queen Elizabeth I by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger of 1592 is a perfect example. It is an allegorical work in which she stands on her country; and sun and storm are depicted to each side of her in the sky. A second strand is the 'Family' portrait of which Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel and Surrey by Peter Paul Rubens is an example. A third strand is the 'Professional' portrait, and Benjamin Jonson painted by Abraham van Blyenberch, shows someone famous for what he did rather than who he was. It was an important shift. The fourth strand is the 'Individual' and the Prince of Wales by Richard Cosway, in a miniature, demonstrates this. The miniature may have died out, but the modern use of photographs in purses and wallets, corresponds to the same desire to hok) someone's image close. The fifth and final strand is the 'Memorial' portrait, for which I would choose John Keats by Joseph Severn, painted after the poet's death as a memory of when he had seen him before he was ill.

Secondly I would ask how have the terms of portraiture changed within the modern world? Photography changes both the situation and the position of painted portraits within western society and within the field of circulated imagery. From 1839 there exists a means of making life-like and -although not initially instant - telling records of a specific occasion. Time is captured in quite a new way By the 1880s shorter exposures were possible with the development of gelatin film stock, and from this comes the creation of a 'snapshot' with everything that implies in the fleeting expression of un-posed subjects and a cropped or foreshortened image.

In this new modern world, the photograph might be seen to displace the painted portrait, as the new photographic print does its mimetic work better. Other commentators have emphasised the psychological explorations within early 20th century society, as exemplified by Ibsen's plays or Sigmund Freud's writings. This new search for the interior self might make exterior depiction seem less important.

Another view puts greater stress on the more anonymous position of the individual within an increasingly mechanised world an individual is simply less relevant in a new mass society. Still another sees the clashes between proletariat and bourgeois power, between unions and government, and between men and women, as the defining characteristics of early 20th century life.

Comparing paintings and photographs of famous figures of the 20th century - whether Winston Churchill or Margaret Thatcher - we are not surprised that the photograph might in some instances convey rather better the character and power of the subject against the equivalent painted portrait. But my proposition here is not that photography has displaced painted portraiture, but that it has changed the encounter between subject and artist, and altered part of the context in which painted portraits are created.

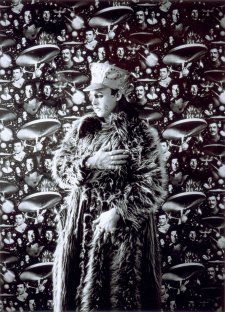

Thirdly I would then ask what other forms of portraiture have become effective in the contemporary world? Photography has affected the whole arena of portraiture: the character and the context. It has also developed and spawned new media, digital photographs and video images being one arena. There are new digital opportunities and the commissioned portrait of David Beckham by Sam Taylor-Wood is the perfect example of a new kind of portrait.

So why do painted portraits still matter today? Do we now have a greater or different public for portraiture? Are the characteristics of authority and authenticity still relevant or true?

The fast changing landscape of surveillance and the globalisation of digital imagery calls for the counterpoint of intense, 'local' imagery contained within a painting. The possibilities of allegory and complex meaning are distinct: the symbolic realm can come to the fore. The conveying of character in a painted portrait is specific and dynamic. There is a process described through paint - an intensity to the relationship between artist and sitter - which produces a different character from the medium of photography. And it is this intensity, often freed from the conventions of previous periods which, gives a great portrait its authority. The painted portrait endures.