Amongst Australia's 'actors on the stage of human life' the scientist has been an abiding presence. Portraits of scientists can be spotted almost invariably in exhibitions or illustrated publications celebrating and commemorating the achievements of eminent Australians. The role, the reputation and portrayal of the scientist has been far from static, as the selection in Australia and the Nobel Prize reveals. Scientists tend to conjure up images of men in white coats in labs but this is just one stereotype in an evolving history of how we have perceived scientists, and how their profession has been understood over the years.

During the 18th century scientists were at the forefront of the Enlightenment. They were presented as men of the world documenting and analysing natural phenomena, not inhabiting laboratories. The portrait of one of our earliest and most renowned scientists, the botanist Sir Joseph Banks, is a typical image of the scientist of the Enlightenment. He sits at a desk with his left arm resting on sheets of paper and with a quill and, significantly, a globe of the world next to him. The globe emphasises that he has the disposition of the explorer ready to travel to distant lands; he is poised to stand with his right arm ready to lift him from his chair. Through the window we see the lands that he will visit, observe and record.

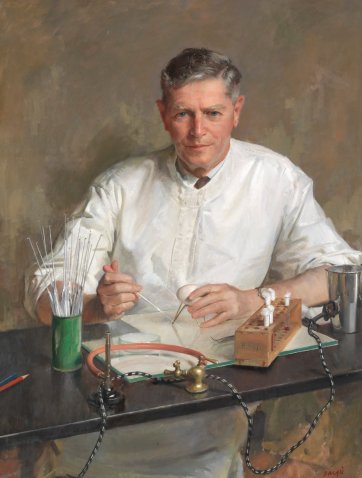

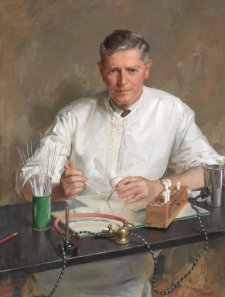

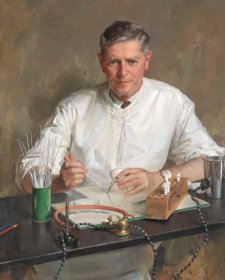

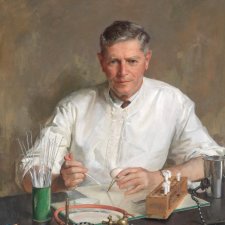

This portrait is in striking contrast to William Dargie's portrait of Sir Macfarlane Burnet, with the scientist now confined to the laboratory. At first glance portraits of scientists may seem to be uncomplicated but as the art critic Baudelaire once observed 'if you care to examine the matter closely, nothing in a portrait is a matter of indifference. Gesture, grimace, clothing, even decor - all must serve to realise a character.' It is too easy to accept a portrait as an uncomplicated likeness and not realise that it is a highly constructed image that needs to be historically situated and which reveals a great deal not only about the sitter but about the society that created it.

By the 20th century science had become increasingly associated with lab work and with experimentation and the portraits reflect this changing emphasis. In Dargie's portrait of Burnet there is no sense of a world beyond and the focus is on the experiment that Burnet is conducting. Burnet was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1960 for his discovery of immunological tolerance. As part of his research into the immune system he refined methods for growing viruses in fowl embryos in eggs. He discovered that adult hens infected with influenza develop antibodies yet chickens born from eggs innoculated with the virus do not develop antibodies. From here he was able to develop his theories of acquired immunological intolerance.

It is this work on eggs that Burnet is pursuing in Dargie's portrait. Burnet acknowledges us but conveys the impression that he is hoping to be only momentarily distracted from his work. He will shortly need to turn back to the exacting task of injecting the virus into the egg he delicately holds in his left hand. To add to the sense that we are invaders, the table acts as a barrier and the flimsy cords and pipes, along with the precariously placed test-tubes and the Bunsen burner, act to separate us from Burnet and his highly specialised workplace.

Through 'lab' portraits the genius and critical skills of the scientist is clearly conveyed. A similar message is apparent in Allan Gwynne-Jones' portrait of Lord Florey. We see Florey seated in front of rows of books in solid timber bookcases. The portrait was painted in 1963 when Florey had already received a number of accolades for his discovery of penicillin, from receiving the Nobel Prize to his appointment as President of the Royal Society. Florey's involvement and success in prestigious institutions is conveyed through such trappings of establishment as his red academic robes. Once again he appears to be a reluctant sitter, as he looks up and acknowledges the viewer somewhat unwillingly. He has been reading; he holds the book open with the intention of returning to it, and his left hand tightly grasps the arm of the chair creating a sense of tension. Often hands in portraits convey as much about the mood and personality of the sitter as the face and this is particularly so in portraits of scientists. Their hands are crucial to their work and their ability to experiment and therefore they take on heightened importance.

For centuries portraiture has been concerned with documentation and recording likenesses for posterity. Since the 19th century and the establishment of portrait galleries, the idea that images of great men (and it was almost invariably men) had a beneficial effect on society was intrinsic to creating a likeness.

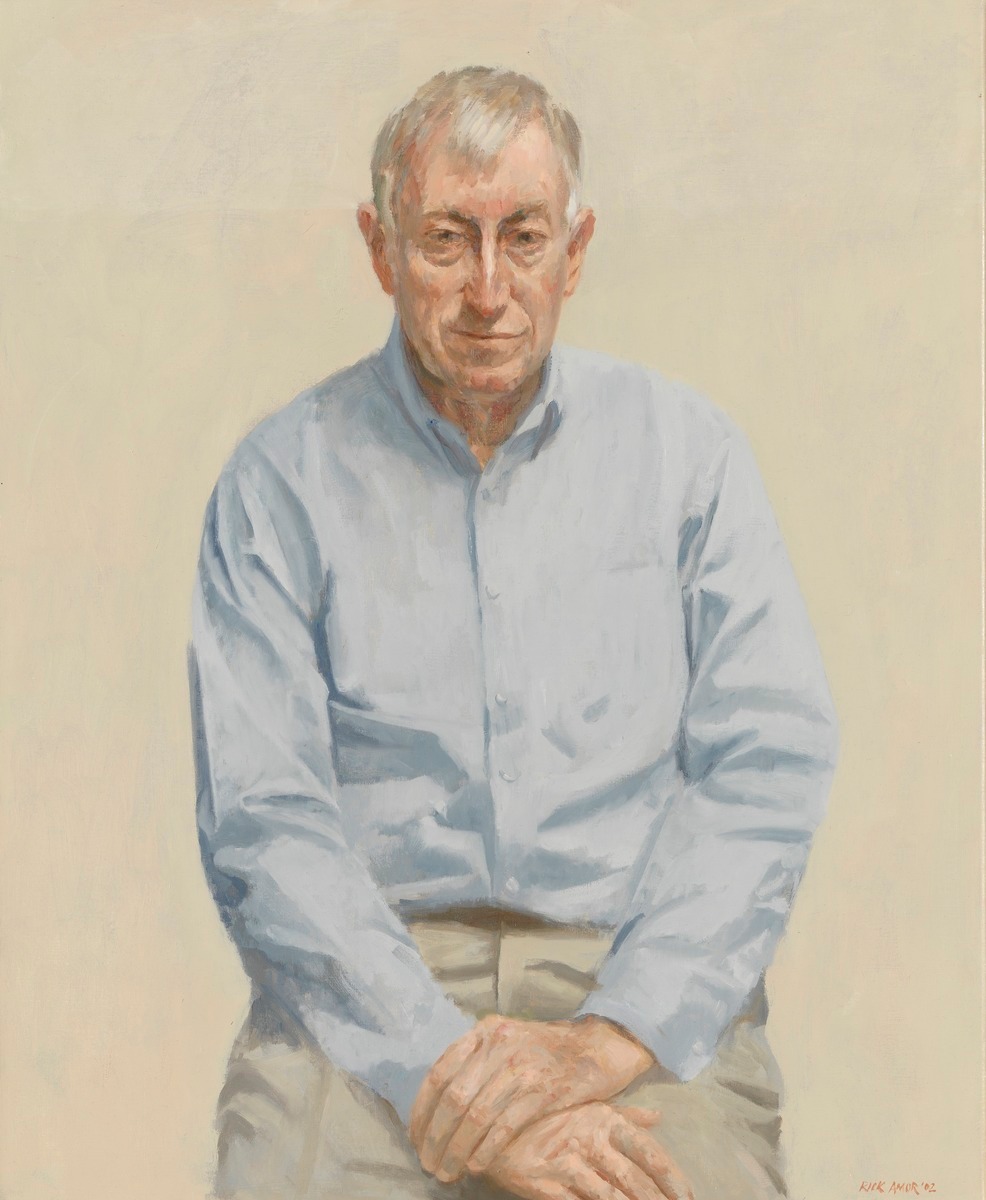

Through the 20th century, the emphasis in portraiture increasingly shifted to offering insight into the personality of the sitter and not just their deeds and professional achievements. We can see this inclination towards examining the person behind the lab coat in a number of portraits in the exhibition, particularly the paintings of Peter Doherty and Rolf Zinkernagel. These scientists were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for their work on the immune system and how virus-infected cells are recognised by the body. There is nothing explicit in either portrait to indicate what they have achieved or that they were indeed scientists. Both are positioned in front of blank walls and are casually dressed. We do not see any of the accoutrements and paraphernalia associated with scientific endeavour; no equipment for experimentation, no white lab coats. There are no props to distract us or hinder our approach and we are invited to view the scientists as individuals.

There is a sense of gravity in these images and we are aware that we are in the presence of thoughtful, wise and reflective men. In the portrait of Zinkernagel his forehead is slightly creased and while he is clearly seated for his portrait to be painted he is preoccupied. Once again his hands are telling with his fingers interlaced and with each hand struggling to keep the other still. Similarly in the Doherty portrait one hand holds down the other and they are prominently positioned. Zinkernagel's watch is contrasted against his pale shirt and is given a prominence that alludes to his practical, industrious nature and indicates that he is conscious of time.

The aim of portraiture to reveal more of the character of the sitter coincides with a period of enormous scientific change in which the broader society has become increasingly concerned about the personalities directing experimentation and discovery. It can be argued that as science has become more embroiled in moral and ethical issues, the public has become more interested in the nature, motives and values of its scientists.