He now divides his time between Thailand and Japan, where his wife originates from. Encompassing sculpture, video, painting, installation, photography and performance, Rawanchaikul’s practice is nonetheless grounded in interaction and collaboration with communities, both real and imagined. An ongoing project has seen Navin seek out other Navins throughout the world. Other works have appropriated popular culture and advertising mediums such as comics and billboards, and used them as mediums to distribute contemporary art to as broad an audience as possible.

Rawanchaikul has also established Navin Productions, a team of artists, photographers, painters, designers, illustrators and ‘advisors’, who assist him to realise his often lavish interventions into public spaces, print media, film and galleries.

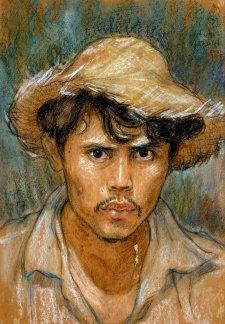

The many selves of Navin Rawanchaikul

Navin Rawanchaikul has largely lived his life as the ‘other’, first through birth and then choice. Born of Hindu Punjabi parentage in the Northern Thai city of Chiang Mai, from very early in life he has been aware of and negotiated his position as insider/outsider, as a ‘khaek’, within his own society.1 A position, even further augmented since the notion of home has been divided between Chiang Mai and Fukuoka where his wife and daughter reside. The ambiguity of identity – Thai, Indian or Japanese – has been accentuated on numerous occasions during his near two-decade career by the curatorial fixation to label artists by nation. However, in Rawanchaikul’s case straddling a number of worlds and being culturally ‘other’ has been advantageous. It has provided a particular acuity in artistic observation coupled with a seemingly unquenchable thirst for investigative storytelling around culture, history and identity. It may also explain his ease of manner when negotiating disparate communities and the ensuing participatory interventions, and his uncanny ability to become immersed in elaborate autobiographical narratives about identity that merge social history with fantastical worlds.

Within these varied epic narratives Rawanchaikul invariably plays the lead. The self underpins all the imaginative, seemingly eccentric, exploratory journeys with autobiography and self-representation ever obvious and self-realisation continually explored. In recent years the idea of self has been extended and often incorporates familial representation; his wife and daughter and at times ancestors from the Punjab provide counterpoints and further layers to the narratives. Even though this all-consuming focus on one’s self may at first seem self-obsessive, paradoxically, community inclusivity and accessibility remain central to his practice. Rawanchaikul uses the self, positioned within these parodied autobiographical narratives, to humour and entertain but ultimately to actively bring people together and engage them with his enquiries. Most of his narratives are seeded by personal incidents and evolve around an journeying of discovery around his identity is some shape or form, however the resultant he targets are just as likely to be stall owners in a Chiang Mai market and taxi drivers in Bangkok, as the art world itself.

His own position, and urgency formed the foundation for many of his collaborative projects such as Taxi Gallery, Super(m)art, Fly with Me to Another World, Navin’s Sala and Navin Party. By asking the question ‘who am I?’ Rawanchaikul explores and exploits his own image to bring people together and inspire meaningful dialogues on the nature of art and society, looking at others as a way, in part, of seeing himself more clearly.

Christine Clark

Exhibitions Manager

National Portrait Gallery, Australia

1 Kheak is the Thai word for stranger or guest. A slang and somewhat derogatory term, it usually denotes Indian migrants.