For a long time at the portrait gallery we've been thinking about doing a show that looks at the process of portraiture, from the initial meeting between subject and artist. It might be from the artist's preparatory drawings for the work through to the finished work, the kind of techniques that are employed, the relationship that builds up between artist and sitter and so on. And looking at the resources within our own collection I found this group of beautiful drawings by Jenny Sages. The joy of portraiture is to be able to combine and recombine portraits in various ways, so that they tell different stories all the time. And that's what we've done with three of the large Jenny Sages' portraits we have now in our collection. Now they came into the collection along with beautiful suites of preparatory drawings in the case of Emily Kame Kngwarreye who's behind me. In the form of drawings of dances in rehearsal in the case of Irina Baranova, or in the form of works that show how a portrait could have evolved very differently from the way that it did, in the case of Helen Garner.

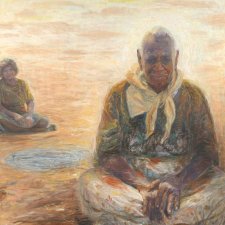

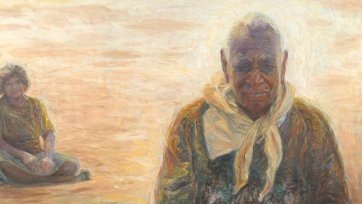

Now the work behind me, Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Lily, was the very first work purchased for the collection of the National Portrait Gallery back in 1998. And it was a very important statement for the new portrait gallery. Andrew Sayers, our inaugural director, wanted to make a clear declaration that the portrait gallery wasn't going to be about men in suits, stuffy boardroom portraits, of white Anglo Saxon Protestant men. Jenny Sages got a plane. Jenny is very charming and she catched a ride on a plane with some German curators who were going to see Emily's work. Emily hadn't been working for very long at that stage. In fact, Jenny had been painting for longer than Emily had. Emily was 83 at the time and Jenny was about 51 I suppose. But when Emily saw Jenny, she said, "You are small like me." And she assumed Jenny was the same age as she was, and Jenny took that on the chin very gracefully, and she sat down with Emily on the dusty ground, and they talked like two 83 year olds. And what we have in our collections of drawings of Emily that Jenny poured onto paper as she was sitting with her is a record of their conversation and a record of Emily's gestures as they sat there talking together. And these drawings are annotated with phrases like, "I like your hat." "You are small like me." "Do you have children?" "Then you have to keep working." And eventually Emily got very tired of the process. She said, "My back hurts, does yours?" And then she said, "Are you finished? I've had enough."

This is an exhibition about the process of portraiture. But how do you show that when somebody has made a portrait, in this case, a self-portrait, with absolutely no preparation what-so-ever? There are no drawings. There are no photographs. There's nothing. Jenny looked at herself in the mirror, and she made her own portrait, then and there. When I said to Jenny, "Well, if we're gonna talk about the process of portraiture, what are we gonna put with your self portrait?" She said, "Well, the process of my self-portrait is me! It's my life. It's what I do. It's what I am. It's what I live for." But she's not comfortable with making a portrait of herself. And the result is this portrait, where she's stepping out, as it were, of the composition. She's barely there. She looks as if she's talking to somebody over here. She's not facing the viewer. She's not presenting herself in full-face. She's presenting herself on the periphery. And she's filled the space in the rest of her portrait with words, words that are not her own. They're words by the poet, Anna Akhmatova, a Russian poet from the early 20th century. And that's because Jenny, late in life, began to connect very strongly with her own background as a Russian growing up in Shanghai. It's an uncompromising work. It's an unflattering work, but it's executed in Jenny's characteristic medium, which is encaustic on board. To make these portraits, Jenny pours wax onto a board, and when the wax hardens, she smooths it out, and when the wax hardens, she rubs pigment into the wax to colour it. She very rarely uses a brush, but she pokes at the surface of her works with anything she can lay her hands on, kitchen knives, etching tools, anything with a bit of a sharp edge that she can worry the surface of her work, and then she rubs in more colour that adheres, sticks in the grooves that she's made. And that's how Jenny gets this beautiful sheen on the surface of her works, which glows with a kind of natural glow. When I saw this book at Jenny's place, I just had to have it, because it's, it is the tangible manifestation of Jenny's enthusiastic, effervescent personality. I've never seen a book with so many flags in it.

This is one of Jenny Sages' characteristic works. She's not a portraitous. She's an abstract landscape painter. And she became an abstract landscape painter in a fell swoop. For about 30 years, Jenny worked for magazines, notably Vogue, as a fashion illustrator and a travel writer. But it wasn't until 1983 when she was 50 that she took a trip to the Australian inland. She went to the Kimberley region of West Australia, and near the Bungle Bungles, and she walked through that country. And it was there, that this little woman, born in Shanghai, of Russian heritage, transported to Sydney, studied in New York, worked for Vogue, travelled all over the place. It was there, in western Australia that Jenny found a real connection to place. And from that moment, her life, as she had known, just dropped away. This one again is made using encaustic, but here Jenny smoothed the surface of the wax and rubbed in a pale, yellow, boney pigment to produce a surface that really is like something that is emanated from nature, from the ground. It's boney. It's stony. It's ivory-like. It's shiny. It's highly polished. It's smooth, and she graven lines into this surface and rubbed in small areas of pigment into these crevices that she's dug out here. And there's something in it that's a little bit like DNA. There's something in it that's like a primitive protozoan life form. There's something worm-like about it. You can see it as a series of parts. Hence the name of this exhibition, "Jenny Sages Parts to Portraiture." Jenny has literally taken her path through the Australian country, and she has come on that journey of portraiture, of abstract work, of painting, of bringing forth a body of beautiful work such as this, finished two weeks ago, specifically for the purpose of this exhibition.

These works combine Jenny's love of textures of natural materials with her love of family. She went through her family photograph albums, and she took photographs from them and copied them onto these red cedar panels. And the result is these works on wood. There are 12 of them that sit in Jenny's bedroom of her family that she has drawn on to the wood of her own deck in Double Bay. The extraordinary thing for me, looking at this portrait of Helen Garner is how when I come up close to it, it resolves, or it fragments into a series of landscapes, of desert landscapes, of desiccated, dry earth, with rivulets through it, with scored erosion lines through it. This area here of the elbow looks like a crumpled piece of earth, and the hair looks like a course garden mulch. It looks like leaf litter. It looks like forest litter. And then when you're up close, the colours in the face of Helen Garner are like the colours of the desert. There's not only this red and yellow and ochre, but up close this most beautiful, pure, gray-blue, and in the cup of this hand, it's like the sun going down in the desert. You can see the deep shadow cast here in this very organically coloured hand. Helen Garner said when she looked at this portrait, she thought her hand looked kind of tough. That was her word, but she likes the portrait a lot. And she's a woman of strong opinions. Anyone who's read her books knows that. She's one of our clearest and most clear-headed writers. And Jenny Sages approached her, because she admired her writing. It wasn't that Jenny and Helen had met at some arts event, or some cocktail party, or opening, or theatre. It was Jenny approaching Helen, because she loved Helen's writing so much. And she had absorbed things that Helen had said, and Helen had become part of her life, part of her imagination before she ever approached her. And Jenny wrote to Helen and said that she's like to paint a portrait of Helen with her sisters who appear in Helen's collection of nonfiction stories, true stories. Helen said, "You've got to be joking. My sisters would never agree." And in the end, after a few more letters of negotiation, Helen and Jenny met in Melbourne and then in Sydney, and you can see in the works that accompany this large portrait in the exhibition that a warm relationship built up between the two women.

Jenny obviously loved portraying Helen. She loved drawing her. She's made this lovely series of oil sketches of Helen, which glow with the light of her studio. Now Jenny Sages saw a film that Catherine Hunter had made about Irina Baranova, and she fell in love. She was enchanted, entranced by Irina. Irina's intonation, her accent reminded her of her own Russian mother. She was enchanted by the older woman's beauty and her gracefulness. And she resolved to meet her if she could. Jenny's own daughter lived up near Byron Bay, and Jenny went up to visit her and there she met Irina Baranova. And this is the portrait that evolved over time as Jenny followed her to Melbourne and made the magnificent series of sketches of dancers in rehearsal that we have in this exhibition. This portrait shows Irini Baranova urgently imparting to a new generation of dancers, steps that she had learned from great choreographers in ballet and creators such as Fokin. It's an uncharacteristically colourful work of Jenny's. You can really sense the layer upon layer of colour that she's rubbed into Irina's face. There's a lot of blue. There are greens. There are purple tones to make a very convincing, very elegant, but very elderly woman's face.