- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

Spanning the 1880s to the 1930s, this collection display celebrates the innovations in art – and life – introduced by the generation of Australians who travelled to London and Paris for experience and inspiration in the decades either side of 1900.

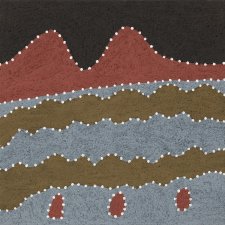

The third row of paintings come from Ngarranggarni (Dreaming).

Born: 1947, Gilbun – Mabel Downs Station, WA

Works: Warmun, WA

The fourth row of paintings interweave Ngarranggarni, memories, relationships and Country.

The second row of paintings recall stories relating to specific sites, experiences and activities.

The first row of paintings depict stories relating to kinship, introducing significant women relatives.

With a mum who was married to a tradie, you’d think it a fair chance that the baby Jesus would have grown up with a dog in the house.

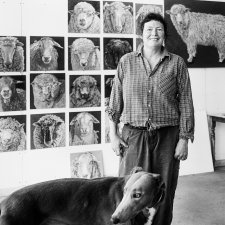

Most well-regarded pictures of chickens show them dead. A reliable way to tell if a chicken in a painting is dead is to check if it’s hanging upside down, because unlike, say, cockatoos, chickens don’t practise inversion for enjoyment in life.

Over the years the young Nicholas Harding got his hands on various mice and guinea pigs, but they served mainly to illustrate the concept of mortality.

Sarah Engledow looks at three decades of Nicholas Harding's portraiture.