- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

When did notions of very fine and very like become separate qualities of a portrait? And what happens to 'very like' in the age of photographic portraiture?

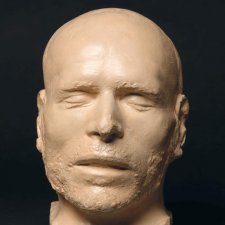

From infamous bushranger to oyster shop display, curator Jo Gilmour explores the life of George Melville.

Last Sunday I had the privilege of appearing at the Canberra Writers’ Festival in conversation with Julia Baird. The subject of our session was Julia’s recent biography, Victoria the Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman who Ruled an Empire.

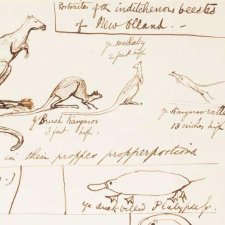

A remarkable undated drawing by Edward Lear (1812–88) blends natural history and whimsy.

The first index I created was for my first book, and, to my astonishment, that was almost twenty-five years ago.

Where do we draw a line between the personal and the historical? Although she died in Melbourne in 1975, when I was not quite eleven years old, I have the vividest memories of my maternal grandmother Helen Borthwick.

There is in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, an English painting, datable on the basis of costume to about 1745, that has for many years exercised my imagination.

I keep going back to Cartier: The Exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia next door, and, within the exhibition, to Princess Marie Louise’s diamond, pearl and sapphire Indian tiara (1923), surely one of the most superb head ornaments ever conceived.

It may seem an odd thing to do at one’s leisure on a beautiful tropical island, but I spent much of my midwinter break a few weeks ago re-reading Bleak House.

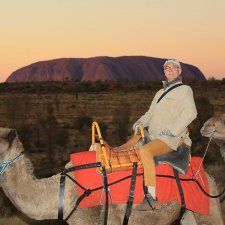

Angus' initial perception of Uluru shifts, as he comes to see it as central to the entire order of Anangu life.