- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

Clara Harriet Crosbie was twelve years old when she went missing in the bush near Yellingbo in the Yarra Valley in May 1885. ‘The child had been sent on a visit to a neighbour about a mile from her mother’s house’, reported the Argus, but ‘as a town-bred girl, of warm affections and quick impulses … she resolved to find her way home, although she did not know the way.’ Faced with the perilous wilds, Clara took shelter in the hollow of a tree for three weeks, crawling to a nearby creek to drink and trying to cooee her way to safety. Her cries for help were eventually heard – by chance – by two men named Cowan and Smith while they were in the vicinity searching for horses. A low sound, ‘like a young blackbird’s whistle’, had caught the acute ear of the two experienced bushmen and they followed the ‘wailing note borne softly on the breeze’ to its source. With the return of each low and piercing cooee, the men at last caught sight of the little girl, frail and woebegone. ‘The little creature was tottering towards us, in her ulster, without shoes or stockings on, but quite sensible’, they recounted. Following her convalescence in the Melbourne Hospital, Clara’s father leased her to Maximilian Kreitmayer, the proprietor of the waxworks on Bourke Street. From August to November 1885, ‘The Latest Attraction, CLARA CROSBIE,’ performed to hordes of intrigued onlookers, explaining ‘How To Live For Three Weeks in the Bush Without Food’. In December 1885 she proceeded to Sydney to repeat the spectacle.

Throughout the nineteenth century there were several accounts of young children from settlements around Melbourne wandering off into the bewildering bush, never to be found again. Several painters of the period, including Frederick McCubbin, William Strutt and S.T. Gill, were inspired by these dramatic, melancholic tales of lost children. The theme also resonated deeply with the populace and became something of a mainstay of nineteenth-century Australian culture. McCubbin’s depiction of a young girl enveloped by bush in Lost (1886) is said to have been inspired by Clara’s story of survival, which McCubbin may well have heard first-hand at Kreitmayer’s Waxworks. In Arthur William Burman’s portrait of Clara, the studio is set up to simulate forbidding bushland, with the lost little girl’s bewildered eyes peering towards the lens. Burman was one of four siblings who followed their father into the photography profession. The various Burmans, and the several studios they operated either individually or in partnership, often sought to cash in on persons of ephemeral celebrity. Among the numerous other subjects of Burman cartes are Eva Carmichael and Tom Pearce, the survivors of the 1878 sinking of the Loch Ard, for example, and Dominick Sonsee, ‘the Smallest Man in the World’, who was exhibiting himself at the Eastern Arcade on Bourke Street in 1880.

Gift of John McPhee 2018

John McPhee (4 portraits)

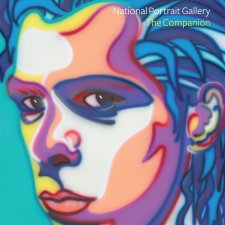

On one level The Companion talks about the most famous and frontline Australians, but on another it tells us about ourselves.

Drawn from the NPG’s burgeoning collection of cartes de visite, Carte-o-mania! celebrates the wit, style and substance of the pocket-sized portraits that were taken and collected like crazy in post-goldrush Australia.

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!