- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

Wylie (c. 1824–?) is thought to have been born near King George's Sound in south-west Western Australia, which would make him a Noongar man. Wylie was about sixteen years old when he met explorer Edward John Eyre, who in January 1840 had overlanded cattle from King George's Sound to Perth. In anticipation of forming an expedition to 'the interior of Australia', Eyre enlisted Wylie's services as a guide, interpreter and general hand and had him brought by ship to Adelaide. Eyre set out from Adelaide in June and Wylie joined the expedition later, in February 1841, at Fowler's Bay. With a party consisting of his assistant, John Baxter, Wylie, and two South Australian Aboriginal men, Joey and Yarry, Eyre set a course west from Fowler's Bay and across the Nullabor, intending to traverse the 1300 or so kilometres to Albany. By March they had covered over 200 kilometres, but by late April the extreme, adverse conditions and dwindling supplies had led to 'a sullen, discontented humour.' Wylie absconded on 22 April but returned to the camp a few days later. On 29 April, Joey and Yarry fled, having stolen firearms and plundered the stores – and having killed Baxter when he caught them red-handed. Eyre suspected Wylie of being cognisant of the plot, initially assuming his loyalty came from 'the fear of the consequences that would attach to the crime should we ever reach a civilized community again', and his fear that 'the other natives, who belonged to quite a different part of Australia to himself, and who spoke a different language, would murder him as unhesitatingly as they had done the white man.' Joey and Yarry shadowed Eyre and Wylie for several days afterwards, 'never ceasing in their importunities to Wylie, until the denseness of the scrub, and the closing in of night, concealed us from each other.'

Wylie chose to continue on with Eyre regardless, proving 'serviceable' as a horseman, hunter, cook, finder of water and bush foods and as a travelling companion. Eyre's account of the journey makes many references to Wylie, often commenting on his appetite and fixation with food and his purportedly questionable loyalty, or indicating his displeasure at what he perceived to be Wylie's ingratitude and self-interested motivations. Eyre seems to have been averse to acknowledging, or incapable of recognising, that he had taken Wylie away from his Country – and that Wylie was as capable of utilising their association as a means to his own ends as much as Eyre used it as a way of achieving his. Towards the end of June, as the pair neared Esperance, they spotted a French whaling vessel, the Mississippi, the captain and crew of which sheltered and fed Eyre and Wylie for twelve days. Wylie again impressed with his 'capacity for eating': 'the immense number of biscuits he devoured, and the amazing rapidity with which they disappeared, not only astounded but absolutely alarmed' the French sailors. Eyre relates that during this time they met with 'a party of natives', two of whom were induced to come aboard. 'As I expected, my boy Wylie fully understood the language spoken in this part of the country and could converse with them fluently', Eyre wrote. He named Rossiter Bay after the Mississippi's captain. With their food supplies replenished and their horses shod, they continued their overland journey, making it to Albany on 7 July. As Eyre's account tells it, Wylie’s people had long given him up for dead, such that his arrival in Albany was greeted with ‘a wild joyous cry … [the] men, women and children, old and young, rushing rapidly up the hill to welcome the wanderer on his return, and to receive their lost one almost from the grave.'

Ultimately, Eyre admitted Wylie's 'fidelity and good conduct' and in his report on the expedition for the colonial secretary 'respectfully recommended him to His Excellency the Governor, as deserving of the favour of the Government for services rendered under circumstances of a peculiarly trying nature.' Wylie was rewarded with a weekly allowance of flour and meat, and the the Agricultural Society of Perth presented him with £2 'on account of his services rendered to Mr Eyre in his late expedition … and a minute was made in the books of the society in testimony of its approval of his conduct.' In the late 1840s it was reported that Wylie had been reappointed as a 'Native Constable for the District of King George's Sound.' Eyre, meanwhile, was awarded the Founder's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society and in 1846 was appointed Governor of New Zealand on a salary of £800 per year plus expenses. He is said to have maintained contact with Wylie long after leaving Australia, and his account of the expedition, published in London in 1845, confirmed Wylie's place as Eyre's co-collaborator in the perilous and remarkable venture.

Robert Neill's drawing of Wylie was engraved for publication in Journals of Expeditions of Discovery into Central Australia and Overland from Adelaide to King George's Sound in the Years 1840-1, Eyre's two-volume account of the journey. This is a loose, hand-coloured plate that has been removed from a copy of that publication.

Purchased 2018

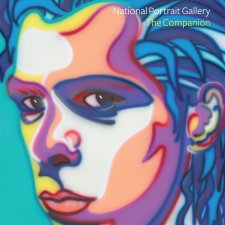

On one level The Companion talks about the most famous and frontline Australians, but on another it tells us about ourselves.

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!