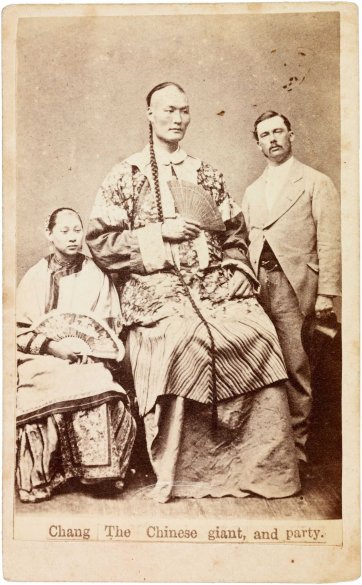

Chang Woo Gow (c. 1846–1893), aka ‘Chang the Chinese Giant’, is believed to have been born in either Fuzhou or Beijing and claimed to be from a line of scholarly, similarly proportioned forbears. He first exhibited himself in London in 1865 at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, which functioned as ‘a cluster of speculative showcases for the miscellaneous entertainers who worked the London circuit’. A woman described as his wife, Kin Foo, and a dwarf were part of the spectacle. Hordes of people were reported to have attended Chang’s levées, readily paying for the privilege of looking upon ‘this most splendid specimen of a man’, dressed in his traditional Chinese robes and diverting his audiences with samples of the several languages he spoke fluently. Having fulfilled further engagements in the UK and Paris, Chang travelled to the USA, appearing in New York, Detroit, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago and San Francisco among other cities before making his way to Melbourne in January 1871. Chang’s inaugural Australian levée was conducted at St. George’s Hall, formerly known as Weston’s Opera House. Like the Egyptian Hall, it was a venue that hosted a diverse assortment of ‘attractions’, such as the mesmerist Madame Sibly, who was ‘manipulating heads’ for packed houses nightly in early March 1871. Chang and his party then proceeded throughout country Victoria. By May they were in Sydney, appearing at the School of Arts with the Australian Tom Thumb, and they subsequently appeared in Maitland, Singleton, Scone, Muswellbrook and Newcastle. In November 1871 Chang married Catherine ‘Kitty’ Santley, a native of Liverpool, England, whom he had met in Geelong. In December it was reported that Chang, his ‘sister’ Kin Foo, and his wife had sailed from Auckland for Shanghai. After a stint with Barnum and Bailey's 'Greatest Show on Earth', Chang retired with his family to Bournemouth, where he opened a tearoom with a sideline in Chinese curios and fabrics.

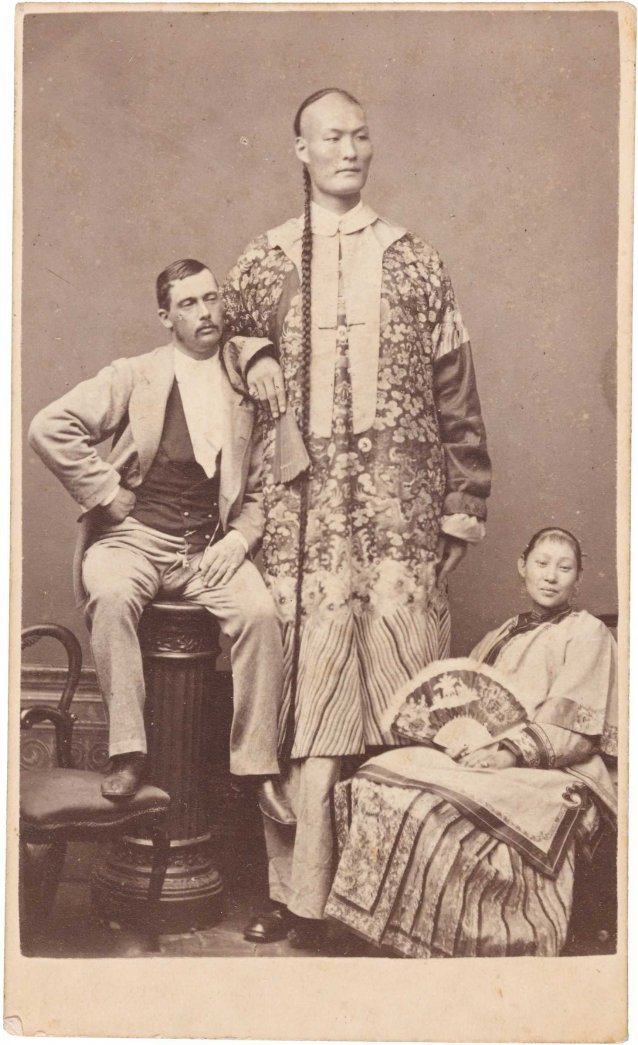

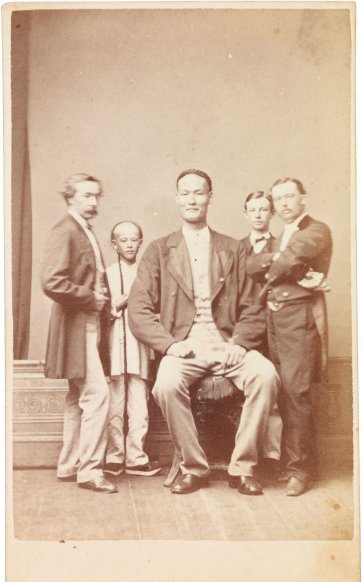

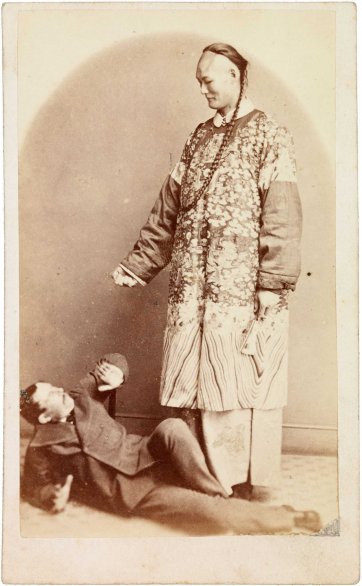

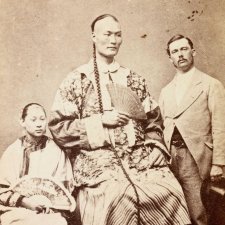

Portraits had a role to play not just in the marketing but in the performances of those in the live exhibit profession, with accounts of Chang’s receptions indicating that the issuing of cartes de visite was part of the whole experience. In Chang’s case, and in keeping with the civility characterising his ‘levees’, the photographs may have been intended to function equally as a memento of having been in his ‘Celestial presence’ and as a miniature conversation piece or quirky, curious souvenir. Among the St George’s Hall tenants when Chang was appearing there in early 1871 was Archibald McDonald (1831–1873), a Canadian-born photographer who had first come to Australia in the late 1840s, working in Melbourne, Geelong, Tasmania and then Melbourne again, and establishing his gallery and studio in St. George’s Hall around 1864. McDonald was consequently among the various photographers to produce cartes of Chang and his entourage. It seems to have been standard to photograph him in either Chinese or English mode; and alongside those of average or dramatically different proportions so as to throw his own into greater relief. Both methods are in evidence in two photographs of Chang bearing McDonald’s studio stamp: one shows Chang and Kin Foo in traditional robes alongside his manager, Edward Partlett – seated atop a pedestal; and the second sees Chang in European clothes, seated, and flanked by four others including a Chinese boy. In April 1871 the Ballarat photographer William Bardwell created a number of cartes of Chang, one of which depicted him with Partlett tucked comfortably underneath his arm.

Purchased 2010

The National Portrait Gallery respects the artistic and intellectual property rights of others. Works of art from the collection are reproduced as per the

Australian Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). The use of images of works from the collection may be restricted under the Act. Requests for a reproduction of a work of art can be made through a

Reproduction request. For further information please contact

NPG Copyright.