- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

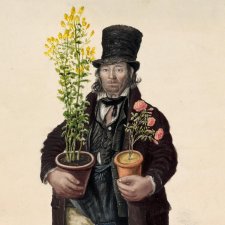

Like the crossing-sweeper, the match-seller was something of a standard genre subject in the early 19th century. Match-sellers appear with some regularity not only in books of costume and cries — ‘I cry my matches in town and in city, / I pray my good mistress come take some for pity’ — but also in oil paintings, where they serve as an emblem or trope of extreme poverty. Barely one-step above outright indigence, but just able to avoid prosecution under vagrancy and mendicancy laws, match-sellers hawked their wares both in the street and over the rails down to the basement kitchens of city houses. As one commentator observed, ‘old women, crippled men, or a mother followed by three or four ragged children, and offering their Matches for sale, excite compassion, and are often relieved, when the importunity of the mere beggar is rejected’. The attempt to maintain a certain dignity, however slender, is recognised by the (albeit ironic) contemporary designation of ‘timber merchant’, and by the binding of the wooden splints in bunches or bundles as bona fide articles of trade: ‘Please, Ma’am, five bunches a ha’penny.’

In Hans Christian Andersen’s excruciatingly pious and sentimental short story of 1846, The little match girl, the eponymous heroine repeatedly strikes matches against the wall in order to keep warm and to feed her hallucinations. Such friction matches — ‘Congreves’ or ‘lucifers’ — were not invented until the 1830s. In Dempsey’s pictures we see the ‘brimstone matches’, slivers of wood angled or sharpened at each end and dipped in sulphur — that were previously used to transfer flame from tinderbox to fire or candle. Their necessity and ubiquity as a household commodity meant that match-sellers were a common sight in Regency streets, and there are in fact five in the Dempsey portfolio. Three of them — an old woman from Woolwich, on the south-east fringe of London, another from East Anglia, probably Norwich, and a man from Salisbury — are anonymous. One is known only by his name: the beggar and ballad-singer Mark Custings of Norwich, also known as Blind Peter.

Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, presented by C. Docker, 1956

Dempsey’s People curator David Hansen chronicles a research tale replete with serendipity, adventure and Tasmanian tigers.

Dempsey’s people: a folio of British street portraits 1824–1844 is the first exhibition to showcase the compelling watercolour images of English street people made by the itinerant English painter John Dempsey throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!