This unique collection will be established over time from a core group of self-portraits currently in The University of Queensland’s collection, including works by Mary Christison, Jeffrey Smart, Ian Burn, Mike Parr, John Nixon and William Yang.

The exhibition launches a new strategic identity for the University Art Museum as it relocates to its new home at the James and Mary Emelia Mayne Centre. It is the first in a series of exhibitions tracing shifting conceptions of selfhood and representation, which will culminate in a major publication on self-portraiture in Australia.

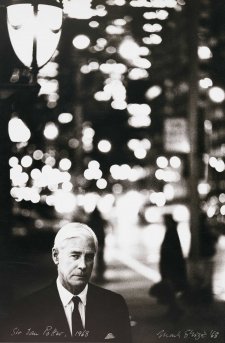

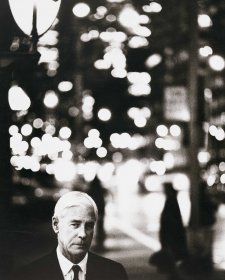

To look within was organised in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery. Andrew Sayers, director of the National Portrait Gallery, co-curated the exhibition with Ross Searle, director of the University Art Museum. Many lenders, including state and national collections, have been generous in supporting the exhibition.

The artist’s self-portrait in Australia

Rarely does the movement of art history fall neatly into the slots allotted accidentally by the turn of centuries. Yet in Australia the history of the artist’s self-portrait does just that. It is largely a phenomenon of the twentieth century, the century in which the personal inner life of the artist became the legitimate subject of art.

Before the 1890s very few self-portraits were made in Australia. This undoubtedly reflects the lack of an art world in Australia for much of the colonial period. By ‘art world’ I mean the institutions and elements that are necessary to allow art to be recognised as an independent and self-sustaining activity. In modern societies these include art schools, public galleries, professional bodies or venues for exhibitions, a developed art market, an art-critical apparatus (newspaper reviewing, journals devoted to art). Without these elements no society can be said to have an art world in which self-portraiture can flourish. In Australia such an art world did not fully exist until the 1890s, although the foundations were being laid down progressively in urban centres from the middle of the century.

The rare examples of self-portraiture in colonial Australia fall into two broad categories. On the one hand, there are portraits intended as a kind of advertisement, painted to make a claim for the artist as a professional and, on the other, those in which the artist made a statement in a more intimate, confessional mode. In the first of these categories, Benjamin Duterrau’s 1837 self-portrait (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart) is typical. The artist, who emigrated to Tasmania in 1832, depicts himself with a folio inscribed with the words: ‘Rafaelle’s Cartoons and School of Athens’. Nothing could more conspicuously declare Duterrau’s somewhat grand sense of himself as a man of taste and a painter in the tradition sweeping back to the Renaissance than this image. In 1849, Duterrau lectured to a Hobart audience on Raphael’s early sixteenth-century fresco painting in the Vatican,The School of Athens, and on that occasion he made specific reference to that painting as an exemplar of the civilising values of education, philosophy and the arts and sciences.

The other important aspect of the practice of art in colonial Australia — the more personal and private aspect — is exemplified in the self-portrait drawings of the Sydney artist Adelaide Ironside, the self-portrait medallions of Theresa Walker and the miniatures of Mary Morton Allport. The circumstances under which each of these works was made varies, but none of these examples is principally a statement of professional prowess. Adelaide Ironside’s 1855 profile drawing (Newcastle Region Art Gallery), enigmatically inscribed ‘Ideal’, is certainly an expression of talent. Yet, as a critic observed of the artist’s work before her departure for study overseas in that same year, it was, as yet, undeveloped talent. Another expression of idealism is found in the self-portrait miniatures of Mary Morton Allport (not included in this exhibition) in which the artist presents herself in the guise of characters from literature.

While it is useful to distinguish between the self-portrait as professional symbol and the self-portrait as personal expression, it would be wrong to draw these lines of distinction too sharply in the colonial context, particularly in the case of exhibited works. Theresa Walker, a sculptor of portrait medallions in wax, included her self-portrait alongside portrait medallions she had executed of public figures such as Governor and Lady Grey in Adelaide’s first art exhibition in 1847. Similarly, while there is no record of its having being publicly exhibited, a selfportrait painted by Theresa Walker’s sister in the latter part of the 1840s, which is among her most finished works, was presumably made for public display.

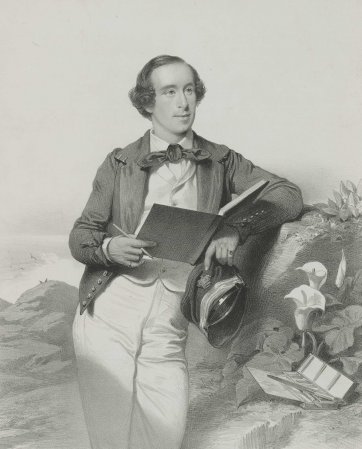

A distinct and important category of this autobiographical variety of self-portrait is found in the works of nineteenth-century traveller artists. Augustus Earle’s paintings and drawings and the prints of George French Angas have strong autobiographical overtones. They were made with the conscious intention of publication; Augustus Earle frequently interpolates himself into his paintings of remote localities, as if to say, ‘I was there’. His writings are not descriptive merely of places and people, but of witnessed events and his own haphazard journeyings. In his painting of the Wentworth Falls, c.1830 (National Library of Australia, Canberra), Earle includes a self-portrait in the guise of the artist in the field, his gun and coat thrown aside as he makes a sketch. Similarly, in an 1849 lithographic self-portrait (National Portrait Gallery of Australia, Canberra), Angas depicts himself standing in a landscape, sketching materials in hand and by his side.

With the development of an art world as we now know it in Australia, the selfportrait became more conspicuous. The greatest proliferation resulted from the rise of separate art schools modelled on European academies. In the course of training to be a painter, the self-portrait proved to be a valuable exercise, a point in the progress towards an artist becoming a fully fledged portraitist. In the work of Hugh Ramsay, however, the self-portrait reaches outside the confines of study into a passionate engagement with the European self-portrait tradition.

The more than two dozen extant self-portraits of Hugh Ramsay were painted during his sojourn in Paris in 1901–02. The body of work ranges from the sketchy to the large-scale, and the mood of the works varies from playful to serious. As Ramsay’s first biographer Edward A. Vidler pointed out, Ramsay’s self-portraits were painted with one eye on the seventeenth-century Spanish painter Velasquez. The rich, sombre tonality of the paintings and the bravura interpretation of fabric are elements that echo the work of the earlier master — and introduce ‘the Velasquez touch’. In the 1901–02 self-portrait included in this exhibition (National Portrait Gallery of Australia, Canberra), Ramsay adopts dress that resembles seventeenth-century garb.

In Paris, Australian artist Ambrose Patterson worked alongside Ramsay. Another enthusiast of Velasquez, Patterson’s complex and self-effacing self portrait, c.1902 (National Gallery of Australia, Canberra), although painted very much under the influence of Ramsay, is among the most complex and original by any Australian artist. Their circle also coincided briefly with that of Australia’s other star pupil of Australian art training of the 1890s, George Lambert. While Ramsay’s life was cut short by his premature death from tuberculosis, Lambert went on to pursue a career as a highly public and professional portraitist.

In Lambert’s thirty-year career, self-portraiture played a particularly varied set of roles. His first self-portrait was painted on his arrival in London in 1900, a tentative experiment. With growing artistic confidence and working in the Edwardian artistic milieu in which making a bold statement mattered, the element of ‘swagger’ in his self-representation increased. Lambert painted himself and with his wife or his children in large set-pieces. Even in his most revealing self-portrait from the English years, Chesham Street 1910 (National Gallery of Australia, Canberra), in which the artist bares his chest for a medical examination, he continues to hide behind the theatrical nature of the revelation. It is a picture that tells us more about Lambert’s ability to paint flesh than about the man.

Lambert’s 1921 self-portrait entitled The official war artist (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne), the last painting he completed in London before his return to Australia, is a more revealing work. The artist, in his singlet and clutching the trappings of army uniform, makes a clear statement about his role as an official war artist. He raises a glass in toast to the real heroes whose exploits he memorialised in post-battle paintings; a label on the canteen he holds is inscribed ‘Dedicated to the Aust. Light Horse, Palestine’.

The crowning statement of Lambert’s self-portrait oeuvre is his Self-portrait with gladioli of 1923, a painting he described as ‘a big effort’ that cost him ‘dearly in money & sweat’. The effort paid off — the ‘amazingly virile’ portrait immediately sold for the colossal sum of £1000. In 1924, it was lent for exhibition at the Royal Academy — confirmation of the artist’s international prestige.

The Royal Academy was the pinnacle of artistic acceptance for an Australian artist, particularly in a period in which the Archibald Prize, first held in 1921, was yet to achieve its great lustre. The Prize ensured that the Art Gallery of New South Wales was the most influential force in Australian portraiture. During the early 1920s, the Art Gallery of New South Wales Trustees requested a number of artists to paint self-portraits for the collection (without payment) and this program resulted in portraits of Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts and Margaret Preston, which are included in this exhibition.

The Archibald Prize, although awarded for a portrait of a distinguished person, has always had its share of self-portraits. When Henry Hanke first won the Prize with a self-portrait in 1934, doubts were expressed about the suitability of a self-portrait to win the Prize. Yet this did not deter self-portrait entrants and the Prize has frequently been awarded to a self-portrait. Two artists have won the Prize twice with self-portraits — Brett Whiteley, in 1976 and 1978, and William Robinson, in 1987 and 1995.

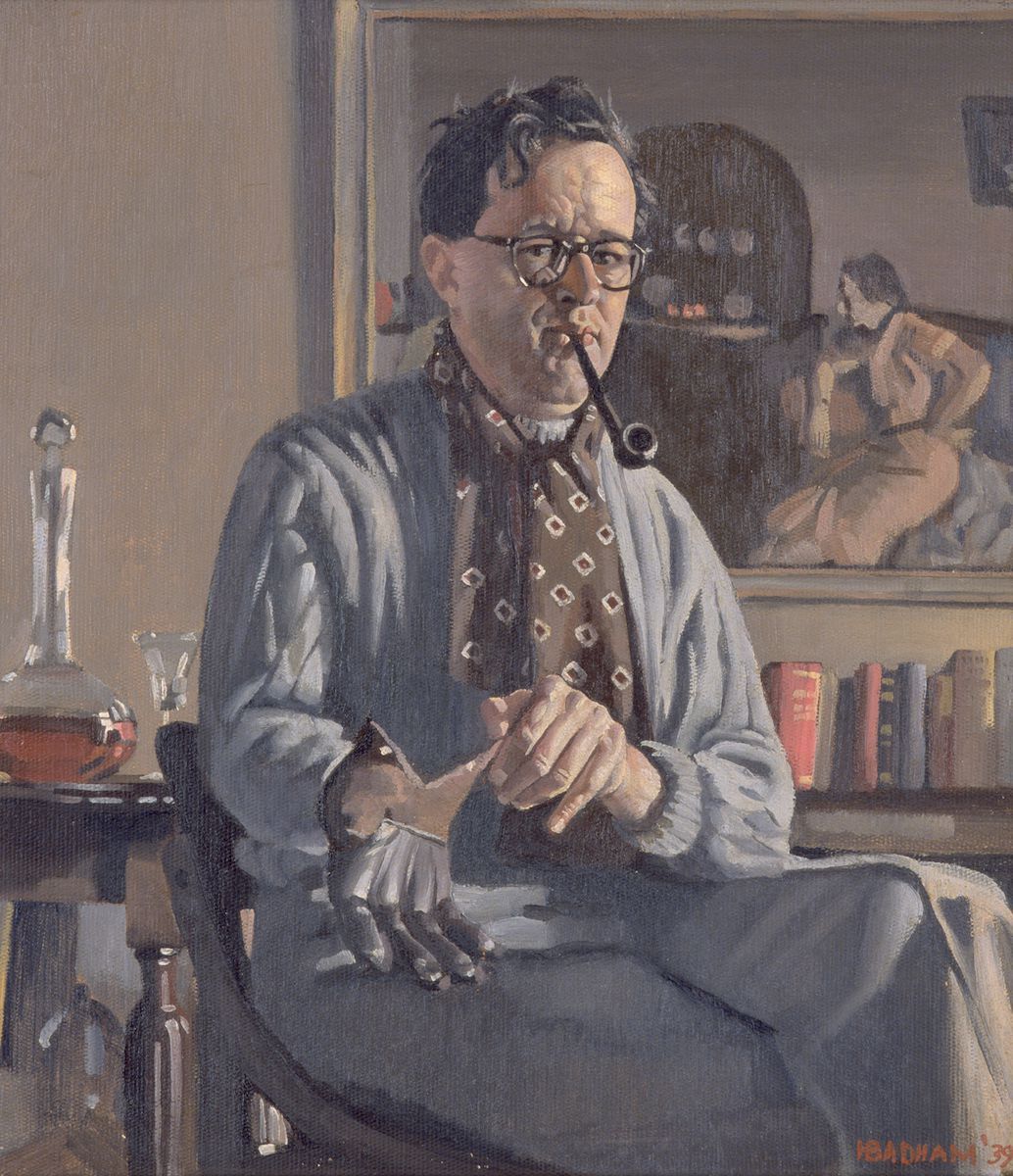

The Archibald Prize was simply one focus of aspiration for young artists of the 1920s and 1930s. Lambert’s status as a professional artist provided a significant role model for young artists, and travelling art scholarships — the most coveted of awards — allowed for overseas travel and study. Lambert had been the recipient of the NSW Society of Artists’ Travelling Scholarship in 1900, and the winner of the 1929 Scholarship, William Dobell, was in many ways Lambert’s true artistic heir. Dobell’s London years (1929–38) provided a solid training in draughtsmanship and he became, like Lambert before him, the most sought-after portraitist of his generation.

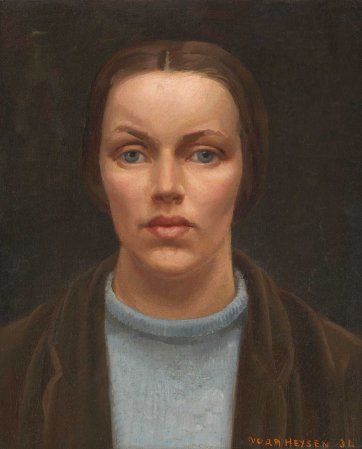

There are strong parallels that can be made between the 1932 self-portrait of Dobell (Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney), Nora Heysen’s 1934 work (National Portrait Gallery of Australia, Canberra) and Stella Bowen’s slightly earlier work (Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide). In each of these selfportraits the face is subjected to intense scrutiny; the background is pared away and gesture is rendered redundant by the close focus on facial features. There is a maximum of detail, yet the face gives little away. This is not public self-portraiture, but self-portraiture to reach private ends, primarily undertaken as self-affirmation. It is a telling fact that each of these self-portraits remained within the orbit of the artist (or family), entering public collections only in recent years.

The self-portrait is fascinating (for artists and audiences) because it combines the common and the unique. There can be very few self-portraits painted in the twentieth century without an awareness of the traditions of the genre. Yet despite the inevitable fact that a self-portrait will partake of the traditions and conventions of self-representation (Velasquez, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Gwen John, Picasso), each self-portrait will be unique, precisely because the subject is unique — an individual whose persona is shaped by specific circumstances, history, identity and aspiration.

Artists are always conscious of the traditions and the historical precursors of the self-portrait. Arthur Boyd reinvented a Rembrandtesque chiaroscuro style in which to paint his youthful self-portrait in 1947; Fred Williams carried echoes of Manet’s self-portraiture into his most considered statement in the genre; and Sidney Nolan ‘took on’ Picasso, applying a modernist fragmentation to his own face. Interestingly, Nolan in 1943 and Fred Williams in 1960–61 were both on the verge of finding entirely original ways of expressing the Australian landscape when they painted their self-portraits. In Nolan’s work, the face appears as though it has a landscape inscribed upon it, while in Williams’s portrait, the transparent brown scumbling he used to construct bush landscapes is used to describe the massive forms in the work. Perhaps the most complete statement of this conjunction of portrait and landscape in current Australian art is James Gleeson’s Portrait of the artist as an evolving landscape 1994 (The James Agapitos & Ray Wilson Collection, NSW). Here the landscape is a cerebral one — literally a ‘mindscape’ that seems to emerge from and inundate the head of the artist.

Gleeson’s self-portrait is the best expression of the approach that suggests the fragmentation of the individual. The face comes apart rather than cohering, or is shattered by the experience of disorientation. A similar fragmented persona, reflecting the temporary and uncertain experience of military posting, is apparent in Eric Thake’s 1945 gouache, Self-portrait in a broken shaving mirror (Private Collection, Geelong). The fragmentation of self-doubt is the theme of many self-portraits, including one of the most profound of all Australian self-portraits, John Olsen’s massive Donde Voy? Self-Portraits in Moments of Doubt 1989 (Private Collection, Sydney).

It could be said that almost all serious artists embark on self-portraiture at some point in their careers. During the latter part of the twentieth century, and in our own time, there is a multitude of ideas embodied in the self-portrait. Sometimes the self-portrait is undertaken as an artistic exercise, sometimes as self-affirmation. It can be a statement of professional allegiance, the expression of relationship or a construction of identity. The self-portraits of Gordon Bennett are exemplary in this regard: the artist creates a complex layering of allusion with which he reflects on his own position as a professional artist and as an Indigenous artist.

Undoubtedly, the most original practitioner of the self-portrait in Australia has been Mike Parr, whose three-decade body of work has accumulated as a vast and complex Self-Portrait Project. Parr’s project bears little relationship to the other self-portraits produced in Australia during this period; in both motivation and effect, Parr’s self-portraits differ fundamentally from those enumerated above. The self in Parr’s work is not a represented persona, but a kind of surface on which the artist acts out a monologue about the nature of representation.

The traditions of self-portrait painting and drawing have proven to be remarkably robust. There are probably more self-portraits being produced in Australia at the beginning of the twenty-first century than at any other time in the nation’s history. This self-portrait activity will continue and will be strengthened and enriched by The University of Queensland’s University Art Museum’s project to concentrate collecting in this area. Over time, the self-portrait collection will build into a rich picture of the life, work and preoccupations of Australian artists from the early twentieth century through to the contemporary era.

Andrew Sayers

Director of the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra.