This is the first in a series of National Portrait Gallery exhibitions to survey the portraits painted by artists who are not thought of, primarily, as portrait painters. Arthur Boyd was such an artist. He is known principally for his mythological subjects and landscapes, and for works which reveal deep human truths. He did not consider himself to be a portrait painter, and in comparison with the total number of his works, the number of portraits is comparatively small. But amongst this small group of works are some powerful and inspired depictions of people.

The earliest portraits set a theme which remained constant throughout Boyd’s career – the preference for subjects drawn from his immediate circle, his family and friends.He began with his parents, Doris and Merric Boyd, with his brothers and sister, and with self-portraits – direct, relaxed sketches painted when the artist was in his mid teens. These paintings are at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum to the extended engagements with the ghosts of his early life which were the subjects of Boyd’s paintings of the late 1960s. The exhibition includes an example of this later series – the sombre Interior with potter and model 1969, painted a decade after the death of his parents, is an imaginative reconstruction of the often fraught personal dynamics of the artist’s early life.

Unlike the benign and relaxed mood of the mid-1930s paintings, Boyd’s work of the late 1930s is tense and expressive. A source of inspiration during this experimental painting period is often cited as the work of his fellow Melbourne artists, in particular, the Jewish refugee Yosl Bergner, a painter of moody streetscapes who was a devotee of European expressionism. Boyd’s vigorous Laughing head 1938 certainly suggests the example of such European expressionist painters as Georges Rouault and Oskar Kokoschka. In this exhibition Laughing head is paired with a work not previously shown, Nude and three heads 1939, a painting in which Boyd departed from the naturalistic colour of his earlier portraits. Neither of these works is a direct portrait (although the face in the upper corner of Nude and three heads is unmistakably a self-portrait), yet the paintings of this time embody some deep humanistic quality, tinged with a kind of brutal directness. They also suggest stories. Nude and three heads relates to a painting of 1938, Three heads, in which, according to the historian Ursula Hoff, the three Boyd brothers impersonate the characters in Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov. The portrait of Barbara Hockey of 1938 has been interpreted by the same historian as taking illness (a Dostoevskian theme) as its subject. While a student at Melbourne University, Hockey had been confined to bed with tuberculosis, which accounts for the subject’s feverish and haggard look so appropriate to Boyd’s mood of heightened expressiveness.

The self-portrait reappears throughout Boyd’s work. Sometimes, as in one of the earliest paintings included here and in the masterly etching of 1962—63, these are relatively straightforward, albeit intensely searching self-portraits. Boyd’s archetypal depictions of the artist in the paintings of the early 1970s – tormented by beasts, grasping at heaps of gold, caged and chained – can also be read as self-portraits. But these later works are to be regarded more as meditations on a generalised condition of the artist than as self-portraits proper.

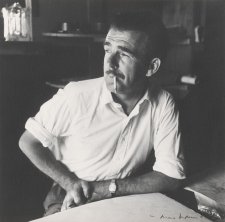

The 1945—46 Self-portrait is a powerfully realised work, one of the great twentieth-century Australian self-portraits. It is an iconic work among Boyd’s portraits of the mid-1940s. Characteristically, these are paintings of the family and of the wider circle of the pottery at Murrumbeena, Melbourne, which Boyd set up with John Perceval and Peter Herbst in 1944. There is a photograph by Albert Tucker which shows the artist with the recently completed self-portrait. It captures the sense of the shared creative environment in which the 1940s portraits were painted.

Many of the subjects of the portraits of the late 1940s were involved in the pottery: Carl Cooper, subject of two major portraits; Valerie Petschack, who married Peter Herbst; Tim and Betty Burstall. Other subjects were students and writers: Max Nicholson, an English student at Melbourne University and a family friend since 1934; the actor Max Dunn; the poet Frank Kellaway; and picture-framer Martin Smith.

Betty Burstall worked at the pottery from time to time. Her face, surrounded by a mass of curly dark hair, was the ideal model for Boyd’s paintings on biblical themes and his decorated ceramics. This exhibition includes the intense head of Betty Burstall painted in 1945 as well as a decorated bowl in which her face appears transformed into that of an angel, surrounded by exuberant animal life. As an example of Boyd’s devotion to Rembrandt, the portrait of Betty Burstall is not alone in this exhibition – at least from the late 1940s, Rembrandt was the inspiration for much of Boyd’s portraiture in which heads are vigorously modelled out of a dark background.

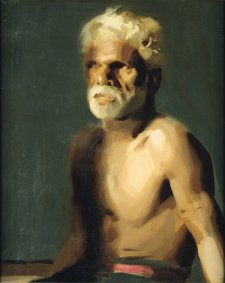

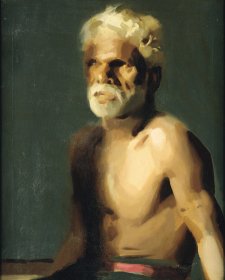

The series of 1940s portraits is brought to a close with two paintings of 1949—50 – one a depiction of defiant (or simply bored) childhood in the portrait of the artist’s daughter Polly; the other of old age, in the portrait of Robert Lindsay.

In his major monograph on Arthur Boyd, published in 1967, Franz Philipp recorded thirty portraits painted between 1945 and 1950. Philipp entitled his brief discussion of Boyd’s sustained phase of portrait painting ‘an interlude’. There was, however, a later burst of portrait painting in Boyd’s career – in London in 1961—66, when he painted at least a further twelve portraits. Again, these paintings took their subjects either from the immediate family or from the artist’s intellectual circle: the actor and director Peter O’Shaughnessy (also the subject of a drawing in his classic role in Gogol’s Diary of a Madman); the publisher Tom Rosenthal; and the philosopher Cameron Jackson.

Boyd only occasionally painted portraits on request or as commissions, and the results were not always successful; he needed friendship, rapport or intimacy as a precondition. His long-standing close relationships with Anne Purves of Australian Galleries, and the dealer and discriminating collector, Joseph Brown, led to two remarkable serial portraits – themes and variations – which collectively express the sitters’ personalities and mood.

The penultimate painting in the exhibition, of the great historian Manning Clark, is one of Boyd’s most poignant and heart-felt portraits. It is a gentle painting, simple and friendly – a man at ease, his dog, a creamy strip of beach and a patch of sunlit bush. Above the artist’s signature and the painting’s date are the words of friendship, ‘for Manning’. The work was painted during Boyd’s six-month residency in Canberra in 1971—72 as the Australian National University’s Creative Arts Fellow. During that time the Boyds visited Manning and Dymphna Clark at their bush retreat at Wapengo on the New South Wales south coast.

In the portrait of Manning Clark, the figure merges with the landscape, even to the sky-blue and yellow-ochre of his clothes. This is as Australian a portrait as Figure on a chair (painted later in the same year in England) is an English portrait. Like the Rembrandt-inspired portraits of Boyd’s early maturity in the 1940s, Figure on a chair is a painting created with full consciousness of all the European traditions of figure painting.

Andrew Sayers

Director, National Portrait Gallery