Looking into the rippling texture of the glass set into an old china cabinet at my home, I do not see an exact image of myself. The distorted figure in front of me is vaguely like me; it’s wearing the same colours and moves in a similar, yet disjointed fashion to how I move. I contemplate my wobbly appearance and wonder if reflections themselves could be considered an ephemeral form of self portraiture.

Defined by the Tate as ‘a portrait of the artist by the artist’,1 self portraiture has continuously been explored and questioned by artists, un-obscuring a path for experimentation for those that follow. Canberra-based artists David Lindesay and Nicci Haynes both use themselves, and their bodies, to create art. However, they have contrasting views of whether that makes their work a self portrait.

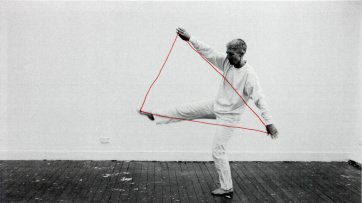

1 2 Photographs from Eye to I series 2022 Both David Lindesay.

I spoke to David Lindesay about his recent Eye to I series, in which he captures the male nude in classically composed black-and-white photographs. Following Lindesay’s direction, the models position themselves around the artist, forming complex arrangements of bodies. The camera, cable and artist remain the only constant element, acting as a link for all the photographs in the series. Blurs and marks on the surface announce the presence of a mirror, reflecting the composition of bodies and allowing Lindesay to return the audience’s gaze.

In contrast to Lindesay’s usual practice of photographing models, for Eye to I he stepped in front of the camera, accompanied by one or more male nudes. He described the decision to make himself the subject of his focus as a necessity during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Unable to shoot models, he took the leap to expose himself, an exercise in becoming more comfortable with his own body. When he was finally able to gather his models, he began the series which he describes as ‘accompanied self-portraits’. Despite always having another figure in each image, Lindesay remains the focus of these portraits through their composition and the direction of his gaze.

It has been suggested that all artists portray an element of themselves in the imagery they create, whether it is representational or abstract. When I asked Lindesay how he would define self portraiture, he agreed with this sentiment, saying that all mediums can warp, distort or abstract but still capture some sort of personal expression. Talking about the nuances of this, Lindesay explained that ‘as long as there’s a mark left by the photographer and the intent is there to be a self portrait, then it is a self portrait’.

Lindesay’s definition of self portraiture reminds me of the American artist and photographer Lee Friedlander. His self portraits rarely include his whole self and only hint at his presence – his reflection in a window or his shadow looming over other people or objects. The lack of physical presence questions whether an artist’s body or face is a fundamental element in self portraiture.

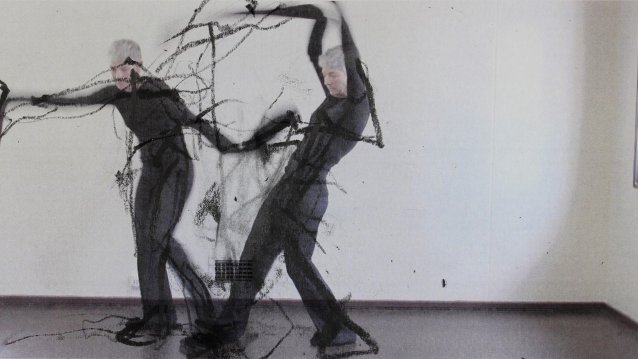

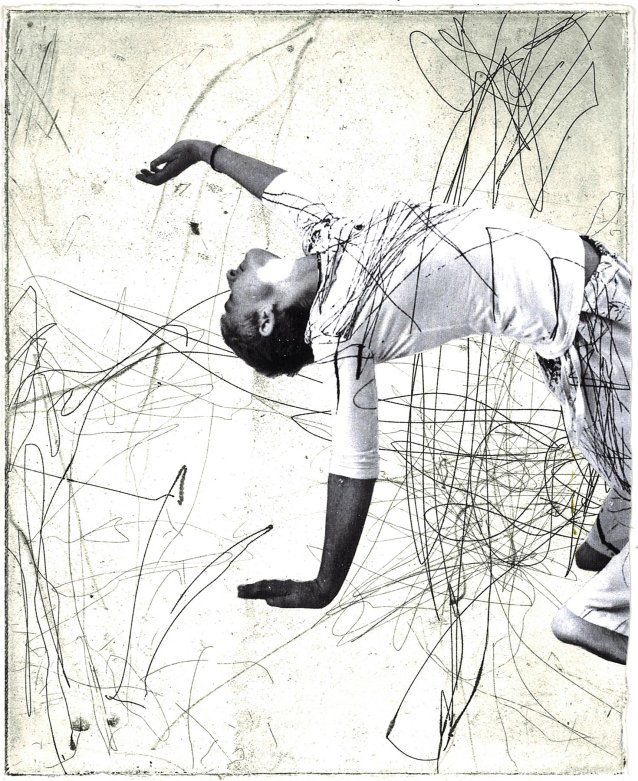

Despite asserting that the subject of her dance/drawing animations must be herself, Nicci Haynes does not consider her works to be self portraits. While her animations feature her full body, the representation of herself is not the main motive for her work. Against empty spaces and muted hues, Haynes moves her body in an intuitive dance, creating gestural marks wherever she goes. She recalls that her Drawing Costume series started when she created a costume for drawing and writing, a black outfit with extended arms and legs. Wanting to suggest the movement of writing like calligraphy through performance and drawing, she created stills of herself moving and dancing while wearing the costume, and then drew over the stills. These were then compiled as a sequence to create moving images. Haynes produced more animations afterwards without her costume, but continued to explore movement and mark-making. Her drawings in these series range from loose and large to fine and structured.

These animated works focus on capturing expression through language and writing. When I asked Haynes if it is important that the subject is herself, she responded: ‘Yes. I remember the sensations and the feeling of the movement when I’m doing the drawing.’ She says that it would be different if someone else was doing the movements and dance – if she had to direct someone, that would take away the spontaneity. For Haynes, calligraphy is a way to express emotion, writing is a gesture, and composing ‘isn’t just an activity of the hand, it involves all of you’.

The parameters and distinctions of what portraiture can be have become very vague and complex. As photographer Susan Bright observed, ‘the deliberately ambiguous strategy of “performed” portraiture is just one of many approaches that artists have adopted to deconstruct and question what a portrait can do and how it functions.’2 Artist Jemima Stehli also questions the nature of self portraiture while including her own body in her work. Similar to Haynes’ animations, Stehli’s Strip series are documented performances. Each image shows the artist taking off her clothes in front of a seated man, who held the camera’s trigger and could choose at what moment to capture the artist. In some of the images Stehli appears confident and you can see the man’s clear look of embarrassment. In others the artist looks vulnerable and the men have a predatory-like gaze. This transfer of control brings into question the idea of self portraiture, and who the artist is.

After our interview, Haynes sent me the text that accompanied a John Nixon exhibition shown at the Canberra Museum and Gallery in November 2022. The text stated that Nixon’s ‘self-portraits were not representations of his physical face or body, but a recording of his ideas that he was giving concrete form to’.3 According to Nixon, his ‘art functions within the fabric of life, rather than illustrating life. The materiality of my work is part of the materiality of experience. I work from the premise that the work of art exists in a “real”, physical rather than illusory world.’4 Nixon’s practice suggests a continuality between life and art, and highlights his belief that ideas are more fundamental to who he is than appearance. Consequently, artworks that have no figure represented are being proclaimed as self portraits, and works that have figures in them can be declared as not.

It is obvious from Lindesay’s and Haynes’ explanations and examples that the term ‘self portrait’ bears diverse connotations. ‘A portrait of the artist, by the artist’ becomes a very general definition when an image, a performance or even an intent can breathe life into a representation of the self. Artists throughout time have used an expanding repertoire of mediums to explain what it is to be human. A dialogue with practicing artists who work with representations of the body, even if they don’t consider their work as portraiture, offers real-time insights into the genre’s evolution and future definition. Perhaps a reflection can be a form of self portraiture.