‘A fella just walked past who is usually ‘all business’: serious face, fast-paced, no time for idle chat – that kinda man. He just stopped and smiled a smile that lit up the chilly morning. No kidding.’

Photographer Stuart Spence wrote this in an email, sent to me from atop a headland looking across a deserted Sydney Harbour on a shining blue day in early June 2020. It was his first response to my asking how he’d been faring during the pandemic, and seeing if he’d like to talk with me for About Face. Stu sent me a set of photographs that were important to him in his career, and I gave him a call later on in June to talk through them. Emailing later, Stu wondered if I could see a through-line in the images.

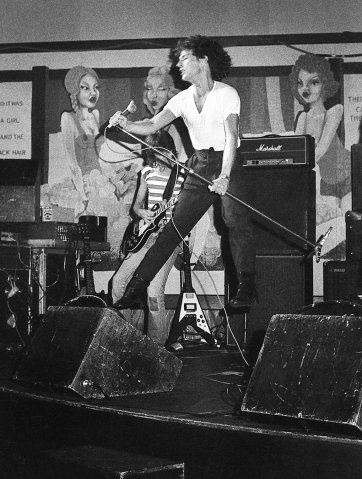

Stu was born in Geelong, but grew up on Sydney’s beaches. ‘We would surf in the daytime and sneak into the pub at night.’ On his eighteenth birthday he took this portrait of Ross Wilson, head back and neck sinews straining, mic stand aloft, rocking out. It’s the type of image that could have appeared with others from Stu’s early gig photography, currently featuring as part of the Portrait Gallery’s spring 2020 exhibition Pub Rock. He went on to work with many of Australia’s foremost musicians, including on publicity and album covers. And the early saltwater shots proved instructive: ‘With surfing photography, it was all about timing and so I had that timing hard-wired in. That training really set me up for capturing the big moments in songs’.

1 Surfing, Noosa, 1970s. 2 Ross Wilson performing with Ross Wilson’s Mondo Rock, as his band was known then, at the Sylvania Hotel, 1978. Both Stuart Spence.

A portfolio of the early rock photography landed Stu a cadetship with Australian Consolidated Press. (‘I presented these shitty prints but the boss saw something in me.’) He began in the darkroom processing film for The Australian Women’s Weekly, providing headings and converted (colour to black and white) prints to the art department in the labour-intensive pre-digital layout process. One of the photographers whose portraits Stu processed was Ern McQuillan (24 of McQuillan’s photographs, spanning several decades, are held in the Gallery’s collection): ‘I loved getting his pictures. He was an old press photographer, hilarious but tough, the real McCoy with his old Graflex camera.’

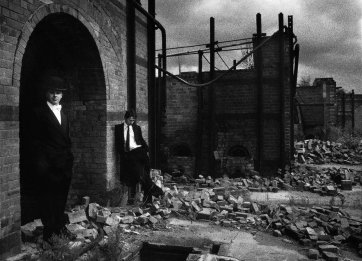

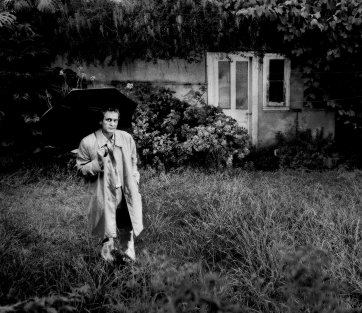

1 Peter Tucker and Alex Cramb, abandoned brickworks, Princes Highway, St Peters, Sydney, 1981. 2 Frank Moorhouse, author, Balmain, c. 1987. Both Stuart Spence.

A formative experience came when a colleague introduced Stu to medium format photography: ‘The idea that you could set something up had never occurred to me … after that, it all got quite theatrical’. In Stu’s first set-up shoot – with friends Peter Tucker and Alex Cramb in 1981 – it’s not so much the documentary realism but rather the surreality of the scene that’s striking. Under Stu’s direction and eye this real abandoned brickworks becomes the vision of an elaborately constructed scene for a film noir – these guys look like they’re poised to rough up Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe. Shot six years later, Stu’s portrait of writer Frank Moorhouse finds this same balance in the overgrown garden and windows; the coat and umbrella are a bit Orson Welles, a bit Graham Greene. Almost comic, almost sinister, almost a movie still, and almost a historical photograph, they are satisfyingly unresolved, in the way some films or novels can be. They play with us. ‘I like stories that are not spoon-fed’, Stu told me in our phone conversation.

‘While still working in darkrooms, I would buy books and try and work out the lighting up in the studio, testing shots with models and borrowing clothes from the Mode magazine fashion room.’ After being surprised to find one of his pictures on the cover of Mode, Stu was suddenly promoted to staff photographer. He would do up to twenty set-ups per day, improvising locations, sourcing props, shooting quickly. It was the heyday of the glossy mag. Editorial features needed original photographic portraiture and Stu moved into this, ‘the most beautiful job’.

1 Stu, 1984. 2 Paul Livingston (aka Flacco), Bondi, Sydney, c. 1988. Both Stuart Spence.

Sydney Morning Herald photography reviewer Robert McFarlane, 27 of whose works are held in the Gallery’s collection, called Stu ‘one of the great entertainers of Australian editorial photography’. It’s easy to see why, given the polished strangeness of the first of his shoots involving substantial art direction. The apples link the work of French surrealist painter Magritte to the absurdist performances of his subject, comedian Paul Livingston, known to 1980s and 1990s audiences simply as ‘Flacco’. ‘And the bath?’, I ask. ‘It had that Dadaist quality I knew Livvo would love. When I suggested it he just agreed, didn’t bat an eyelid!’

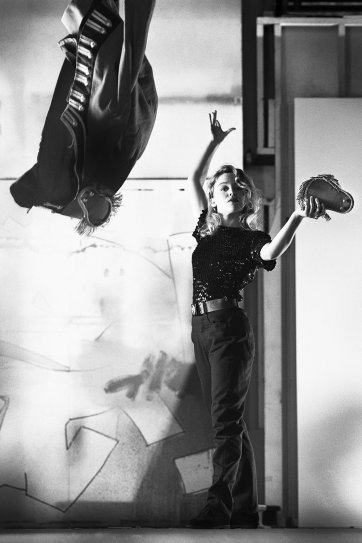

Stu let the inherently strange context of a photographic shoot, a prop, and his subject create open-ended scenes. When working with sitters for editorial assignments from the mid-1980s, he started to bring along a costume faux military jacket, asking the celebrity subject – just for this, his personal project – to do whatever they wanted with it. Evolving into the series and exhibition Salute (1992), this time-capsule records how the rising stars and established luminaries of the time chose to respond to this prop. A young Nicole Kidman sprawls dramatically on the rocks with the jacket thrown over her, deliberately setting up a ‘body found on the beach’ scene that is playfully contradicted by her crossed ankles and direct gaze. Kylie Minogue rips off an epaulette, then tosses the garment back at the photographer with theatrical defiance.

1 Nicole Kidman, Balmoral Beach, Sydney, 1988. 2 Kylie Minogue, Channel 7 Studios, Sydney, 1988. Both Stuart Spence.

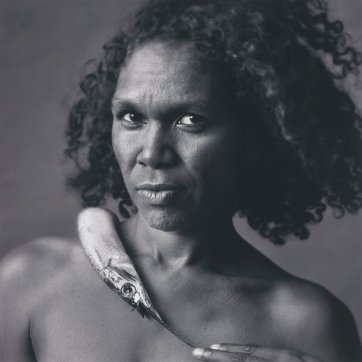

Stu’s portraits of actor Russell Crowe and actress and dancer Ningali Lawford-Wolf are held in the National Portrait Gallery Collection. For a series about water (Watermark, 1997), he provided sitters with a choice of props. Wangkatjungka woman Lawford-Wolf ‘instantly gravitated to the fish, draping it delicately around her neck. She somehow made it look like it belonged there.’ Commissioned by Crowe, Stu took him to his local pub. The resultant image sees the young actor rocking, insolently balanced, the classic childhood manoeuvre clashing with the ‘grown-up’ surrounds. Both sitters are playing.

1 Ningali Lawford-Wolf, 1996 (printed 2016). 2 Russell Crowe, 1995 (printed 2016). Both Stuart Spence.

© Stuart Spence

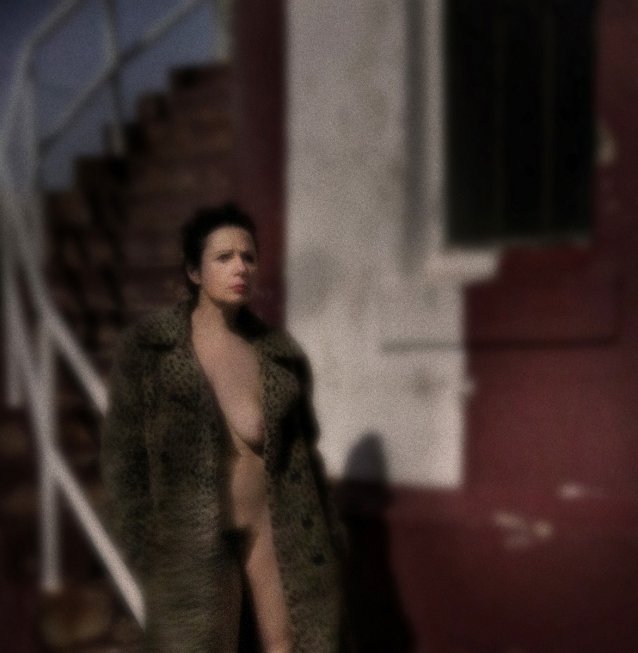

Improvisation and experimentation continued to characterise Stu’s output. In the early 2000s, ‘a friend gave me a brand spanking new Nokia’. He recalls: ‘Sometimes your inner dialogue finds a way to get out … I loved that they [images snapped on the phone] were so free and unbridled and I wasn’t shooting for anybody … it was ‘liberating in a dark, sobering way.’ Stu is about to release a book, Yield, a retrospective of the last fourteen years of his fine art practice that began at this time.

1 Leaving Kansas, c. 2005. 2 Dress Circle, c. 2006. Both Stuart Spence.

Stu’s practice began to develop a counterpoint to the crisp, clean, sharp editorial focus. Leaving Kansas was a crucial image in taking that step. He experimented with titling (‘I think I’m a frustrated song writer’). In his 2009 Sydney Morning Herald review McFarlane found the works in Stu’s exhibition As yet unclear ‘intriguing as much for what they don’t say’. There is that same indeterminacy to these pictures – they feel whimsically or hauntingly incomplete. Aware of this, Stu asked some artist-mates to play with them. He asked them to react and not think too much. Responding in short narratives, dialogues, poems and songs, Stu’s collaborators included writers Luke Davies (Candy) and John Birmingham (He Died with a Felafel in His Hand), along with musicians Tim Freedman of The Whitlams, former Hunters and Collectors frontman Mark Seymour, and former Mental As Anything guitarist Peter O’Doherty (Do yourself a favour and listen to these; they are truly beautiful). Launching As yet unclear at MARS Gallery in Melbourne in 2009, singer-songwriter Paul Kelly said that the photographs ‘set sail from everyday life and launch into the realm of mystery and memory’.

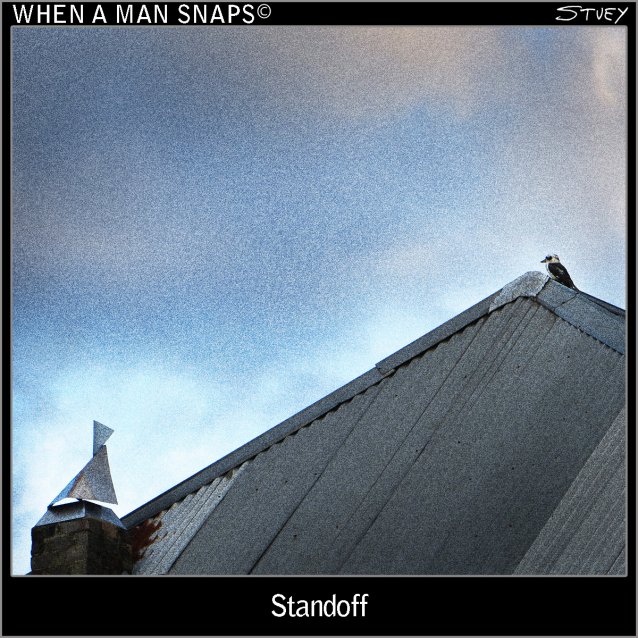

Stu’s irreverent side-hustle When a man snaps (online, books and 2018 Head On exhibition) is pure play. ‘Gather’ feels a truer verb than ‘capture’ for what the photographer is doing here. He harvests odd moments in the world and adds captions (‘I think I’m a frustrated cartoonist’). In his 1993 book That’s the Way I See It, British artist David Hockney wrote, ‘I think you can’t have art without play ... I think you can’t have much human activity of any kind without a sense of playfulness … People tend to forget that play is serious’. It’s a maxim that Stu’s work repeatedly channels.

The 2020 portrait of singer-songwriter Christa Hughes is a new direction for the photographer. ‘I see a difficult vulnerability in leaving some things unresolved’, he declares. ‘If you are jamming you want to be feeling, not thinking.’ Life is full of anarchy, uncertainty, unfinished paths and half-remembered songs. Stu Spence reminds us that, with portraiture – like surfing, music, theatre, film and literature – the playing is the point. Artists can help us keep playing; all we have to do is let a normally serious bloke’s smile light up our chilly morning. This is the through-line I see.