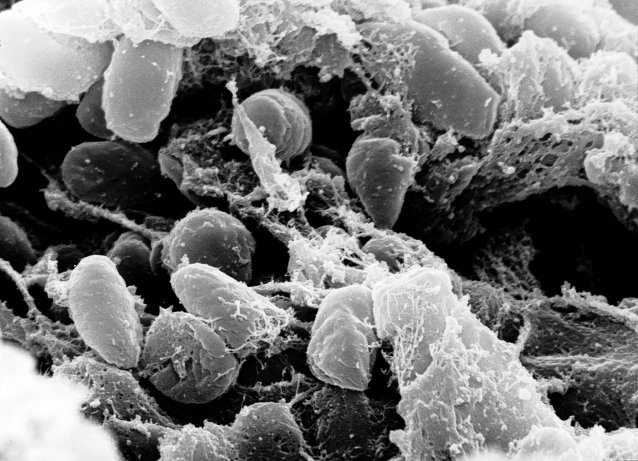

Two aspects of the Black Death are to me entirely revelatory. First, scholars at the time so nearly achieved an understanding of what was going on, but didn’t quite. Extravagant prophylactic religious measures were widespread, mostly a rash of church and shrine building that has long been noted—the Orcagna effect: a sudden, and entirely reasonable embrace of the formal, the hieratic, the penitent, the apocalyptic (look busy, the end is nigh)—but on the whole, educated people clearly understood that the disaster was medical, and the disease fearfully contagious. Yet not an iota of suspicion was directed towards something as commonplace as the black rat. Instead the miasmatic or bad-air theory of infection proved unshakeable. A Spanish bishop was told to stay in his palace, sweltering near a roaring fire, and not let anybody in; naturally sick rats and dying fleas came and went unimpeded. The really remarkable thing is that the bad-air theory was partly correct, inasmuch as what I didn’t mention at the start is that once the rat-to-flea-to-person process of contagion is accomplished, a further devastating human to human step follows, when, as if to amplify the horror, as a consequence of the illness, the sufferer begins to cough up droplets of blood from infected lungs which, airborne, carry plague bacteria into clean lungs and convey the illness into the body of new victims by that route. This is called pneumonic plague and, late, in seventeenth-century England, gave rise to the old nursery rhyme “Ring-a-ring-o’-roses”. (The pocket full of posies was prophylactic, but obviously not effective.)

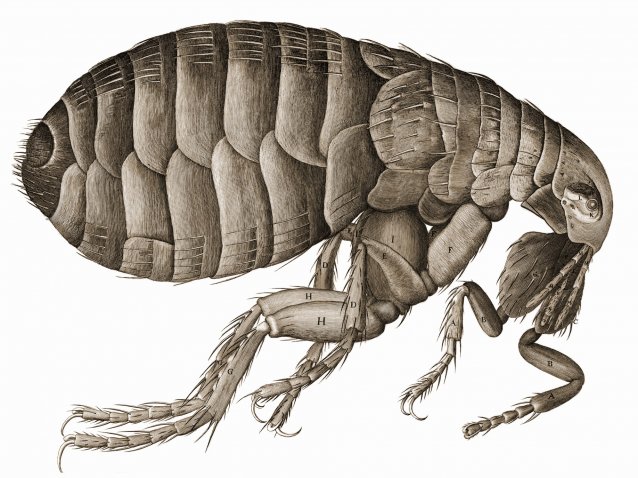

Second, rural communities suffered a consistently higher rate of mortality than the towns, because the attack rate of fleas and of human to human pneumonic plague transmission proved more effective in small clusters of people than in higher densities. So a higher proportion of people in single households were bitten by fleas swarming from each infested nest. From this fact those of us who now live in gigantic cities should take some comfort. And in the mid-fourteenth century the bulk of the population of Europe was spread across the countryside in villages, not concentrated into large towns, where people quickly grasped the need to avoid houses that were overtaken by sickness. Priests administering the last rites in fact became the agents of contagion, while armies of refugees, clinging to the seductive notion of dirty city versus wholesome country, headed for the hills, but merely brought the disease with them in their clothes or luggage or bushels of grain or on their dog, or else increased by several times the likelihood of being bitten by a ravenous, infected flea in the very spot where they prayed they would find sanctuary.

The pandemic began as an epidemic of the bubonic plague in an army of Mongol-led tartars who in 1346 laid siege to a Genoese trading fortress at Kaffa in the Crimea. The heathen army gradually fell ill, panicked, scattered, and perished, but the Genoese (who resisted the siege, but contracted the disease) fled by ship across the Black Sea, and through 1347 deposited ship’s rats, mortally sick sailors and dead bodies in Constantinople and at trading posts far beyond, right around the Mediterranean, in Cyprus, Crete, Sicily, Genoa and Mallorca. Stealthily assisted by the delay in transmission, incubation and spread, the Black Death fanned out from each place, leaping onward, opening up two, three, and sometimes even four prongs of attack (as in Spain). Pilgrims carried it on foot back across the Pyrenees from Santiago de Compostella into southern France. It mowed across Italy, the Balkans, the south of France, the north of Spain and North Africa, and the south of England (1348). (Two ships brought it there from Bordeaux, one of which continued to Dublin.) The rest of France, Spain, England, Ireland, Switzerland, southern Germany, Bohemia and Norway toppled (1349), and then the remainder of Europe – Scotland, the rest of Germany, Denmark and Sweden (1350). Slowing down during the winter months, the pandemic nevertheless wept eastwards across vast territories in Poland, Russia and Ukraine (1351-3). By then it had arrived back at its starting point, the Golden Horde, the region stretching between the northern shores of the Caspian Sea and the Crimea. Only Finland, with next to no population at this date, and Iceland were spared—evidently not a single ship sailed there during the pandemic.