Chinese lacquer, for example, nudged Colombian craftsmen towards entirely new uses for their own exquisite pale green mopa mopa resin, an almost identical substance used in New Spain for similar purposes. Suddenly the art form became far more ambitious. Indigenous carpenters learned complex joinery from example, and the ceaseless demand for church furnishings, bishops’ thrones and confessionals kept them busy for the next 300 years. Meanwhile, the blue-and-white ceramics of Puebla de Los Angeles in Mexico were directly inspired both by Chinese export ware arriving from the Philippines and by maiolica from Europe. At times you see the decorative conventions of both fused in one Mexican vessel. Displaced Islamic motifs also come from both directions, conveyed eastwards from Asia through the textile trade, and from the Chinese end of the Silk Road, and quite separately, westwards, through the lingering influence of Islam in the arts of southern Spain. (Ferdinand and Isabella finally ejected the Nasrids from Granada in 1492, the same year in which Colombus set sail, and barely forty years before the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe, so the Islamic heritage of the Viceroyalty was at first a matter of living memory.)

Glorious Chinese shapes, profiles and types of vessel converse with the rich indigenous ceramic traditions of the Andes, while from 1614 Japanese folding screens or biombos (the criollo name is actually derived from the Japanese term byobu) provided novel formats for conventional oil paintings in the European idiom, principally views of Mexico City. Similarly, indigenous craftsmen took up Chinese ways with tortoiseshell and mother-of-pearl inlay, and employed them with unrestrained vigour. These rapidly evolving New World hybrid species of object reveal not only the impact of the global trade routes, but also found their way back into the markets of Europe and Asia, so that questions arise as to the nature of the reception of Chinese export wares in Spain and Portugal when obviously related New World products often displayed comparable motifs and designs, at times revealing the wildly complicated and intriguing stylistic recension of particular motifs. Where did the connoisseurs stand on the relative merits of each? Did they ever get unusually crude Chinese export and exceptionally refined Puebla wares hopelessly mixed up?

Silver objects, meanwhile—huge gilded altar candlesticks from La Paz; liturgical vessels such as shapely Brazilian flasks for various types of holy oil; weird local monstrances and arm reliquaries; the waist-high solid silver brazier and shovel that were used to heat a church with burning coals on the Altiplano, Bolivia; and above all, the extravagantly eccentric mid-eighteenth-century silver water heater affectionately crafted in the shape of a turkey with splendid plumage (possibly from Lima, ca. 1750)—all these serve to demonstrate the limitless wealth of New Spain, the archetypal El Dorado.

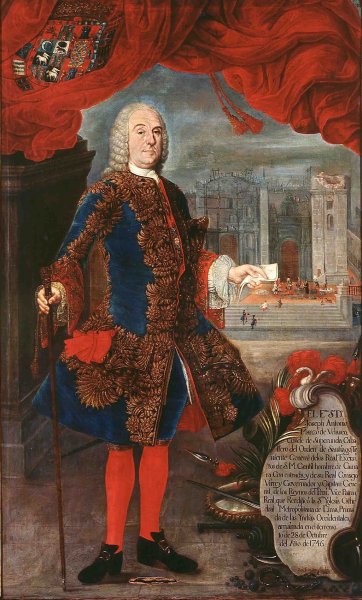

Furniture also demonstrates the busy fusion of European, Asian and indigenous American traditions of design and manufacture. An early eighteenth-century Mexican armchair, for example, the upper portion of which follows a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century Spanish prototype, perches eccentrically on Chinese cabriole legs into which are carved Tlaxcala masks and other indigenous polychrome ornament, all joined, finally, by carved and gilded rocaille cross-members in the latest French fashion. The surprising thing is that this crazy piece of furniture somehow manages to hang together, and that the maker and original customers for similar, whimsically identikit chairs evidently thought so too. In fact, the eighteenth-century New World taste for archaicizing sixteenth-and seventeenth-century Spanish furniture, long after the Bourbons took over the Spanish throne, may have been a deliberate effort to allude to the aristocratic grandeur that was more readily associated with the supplanted Habsburgs, particularly among fantastically rich criollo patrons such as Don Antonio Pacheco y Tovar, Conde de San Javier, and his bride, Dona Teresa Mijares de Solorzano y Tovar, of Caracas in Venezuela. (Seventeenth-and eighteenth-century Spanish vice-regal titles make even the grandest in Debrett seem positively meagre.)