Painters' paradise

Andrew Sayers feels the warmth in the paintings Matthew Perceval made while the sun shone in southern France.

I was introduced to Matthew Perceval's portrait paintings some years ago by the artist's mother, Lady Nolan. Shortly after I started at the National Portrait Gallery, she showed me a series of photographs of portraits Matthew Perceval had painted around the end of the 1960s and early 1970s in France. I was immediately taken by the directness and painterly vigour that seemed to inhabit these paintings, an impression confirmed when I finally encountered the portraits in the flesh in a storage unit in Newcastle, New South Wales.

I had met Matthew Perceval around 1988 when I was working on a book Fifty Years of Perceval Drawings about his father, John Perceval's drawings in which Matthew appears frequently as a child. At that time I was aware of Matthew Perceval as a landscapist, a painter of coast and harbour scenes full of a breezy energy and colour. Many of the landscape subjects I had seen were painted around Newcastle, where he lived in a house perched on the hill above the city. But I was unaware of the group of portraits he had painted when he was first establishing himself as a painter in Europe. These portraits form a kind of time capsule, the fruit of the years in which he and his wife Jutta lived and worked in France between 1967 and 1981.

These portraits, mostly unseen before, along with some made in London and in Australia, form the core of the exhibition currently displayed at the National Portrait Gallery.

Matthew Perceval was twenty-two years of age when he left London, where he had a studio in Belsize Park, and escaped to the painters' paradise of the south of France. He established himself in Tourrettes-sur-Loup where he worked until 1971. He then spent some months painting in Canaules-et-Argentières. A photograph (taken by his mother) shows him at work in a paint-spattered overcoat in a high-walled farm building that served as his studio in these years. Behind him on an easel is one of his portraits of local winegrower André Laval. In 1972 the Percevals moved to Lézan where they stayed until they moved to Paris in 1978.

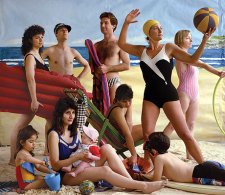

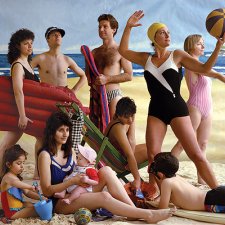

These were fruitful years for the artist - he established himself and began exhibiting, first at the Karoly Foundation in Vence in 1968, then in London at Clytie Jessop's Gallery in 1969 and from 1971 in Australia (at Violet Dulieu's South Yarra Gallery). Perceval was essentially an interpreter of the French rural landscape, although portraits featured in his exhibitions - the first sale of his London exhibition was to Arthur Boyd, who bought his portrait of the printmaker Satish Sharma. Taken as a group though, the portraits he made at the time were a more private concern than the landscapes. The portraits record friendships with fellow artists, such as the expatriate Australian abstract painter Sam Atyeo who lived near Vence and Perceval's Tourrettes-sur-Loup neighbour McDonald, the Scottish painter. The Bertrand couple, Jean-Jacques and Nicole, were potters (and continue to be, working in Anduze). Perceval also recorded local villagers and people passing through, travelling Romanies and Michelle, The student from Haiti.

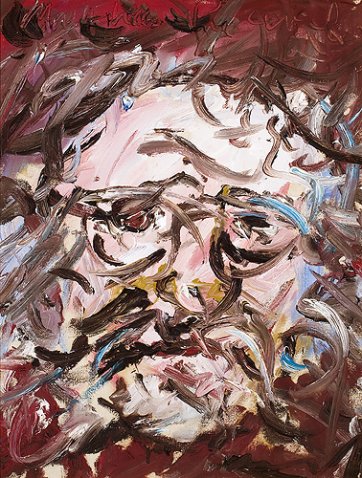

Among the portraits Matthew Perceval painted in his years in France is a strong thread of self portraiture. These self portraits are at times wild and abandoned, so loosely painted that it is as though the artist doubts his own identity. At other times they are humorous, self-deprecating, and at other times there are hints of an Oskar Kokoschka seriousness and intensity .

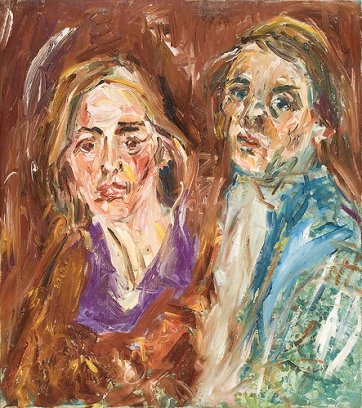

Whilst he chose to work in rural France, Matthew Perceval is not an artist without an inherent tradition to draw upon - he was born into and grew up surrounded by families of artists. For an artist, such a close environment can be a stifling thing and there is no doubt that in the south of France he sought determinedly to mark out his own creative space. Nonetheless, there are links to the visual environment of his youth. In particular, the tendency to make portraits from the people directly around him - his wife and children - is a feature he shares with the approaches taken by his father and by his mother's family, the Boyds, from the 1940s on. As with the direct portrait paintings and drawings of his forebears, Matthew Perceval's portraits of family members are tender and affectionate, not sentimental. The portraits of Jutta are loving but somehow never flattering.

I enjoy Matthew Perceval's portraits as pure painting. Each painting has its own mood, conveyed by colour scheme, and each painting has a quality I can only describe as energy-level, conveyed in the way in which the paint is applied - broadly brushed, flicked, trowelled with the knife or straight out of the mouth of the tube. Yet it would be wrong to overburden his portraits with analysis. His portraiture gains its power from its directness; it is the essence of alla prima painting. The canvas is directly addressed as the arena of the artist's attempts to capture, set down and then to model his direct sense impressions of his subject. His approach gives these portraits a vivid presence.

It is a mark of the success of good portrait painting that it conveys living presences and Matthew Perceval not only succeeds in bringing the villagers of southern France into our world, but also something of its warmth, joy and colour as well.

Andrew Sayers