In recent years I have become fascinated by the so-called Sydney Cove Medallion (1789), a work of art that bridges the 10,000-mile gap between the newly established penal settlement at Port Jackson and the beating heart of Enlightenment England.

The First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay on 18 January 1788. The very next day two French ships, La Boussolle and L’Astrolabe, commanded by Admiral Jean-François de la Pérouse, were spotted out to sea. Eight days later, on 26 January, as Arthur Phillip raised the Union Flag at Sydney Cove and his officers did their best to hurry the rest of the fleet out of Botany Bay, the French dropped anchor there and received from John Hunter a cautious but cordial welcome. The coincidence must have seemed utterly astonishing, and probably not a coincidence at all – although it was indeed purely a chance encounter. Through February and early March Phillip set about establishing his settlement. The most rudimentary wattle-and-daub shelters were built, for which deposits of local clay proved useful but in due course, once the rain set in, depressingly impermanent. However, before the French party set sail on 10 March – never to be heard of again – one of La Pérouse’s naturalists, the Abbé Jean-André Mongez, a mineralogist, ornithologist, entomologist and chemist, casually remarked to Phillip that this Sydney Cove clay might in due course be used to produce excellent pottery, or even bone china.

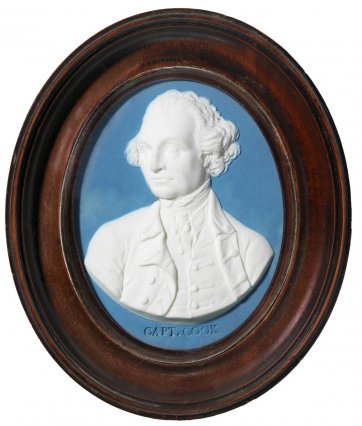

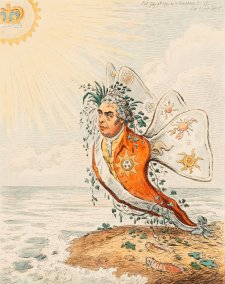

In due course, on 16 November 1788, Phillip despatched aboard H.M.S. Fishburn a sample of this clay to Sir Joseph Banks – repeating the Abbé’s positive assessment; stressing that it was also used by the local Aborigines to decorate their bodies, and mentioning that he would not have thought it worth sending except that Banks himself had mentioned the substance in his account of Captain James Cook’s first circumnavigation (1768-71) – an intriguing but maddening reference because it cannot now be traced. Since many of Banks’s positive assessments of the potential of Botany Bay had proven so depressingly inaccurate, Phillip must have been relieved to be able to furnish some confirmation of his account in the form of the clay, together with samples of an unusual black mineral that had been discovered whilst digging a well. This turned out to be “a species of plumbago, or black-lead”. The parcels reached London in May 1789, and Banks immediately forwarded them to his friend Josiah Wedgwood, a fellow member of the Royal Society. Wedgwood’s Staffordshire pottery, “Etruria”, near Stoke-on-Trent, was well accustomed to testing the properties of batches of clay sent from all over England, Europe, and much farther afield – for example from China and North America.

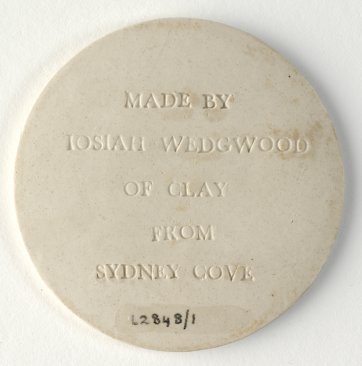

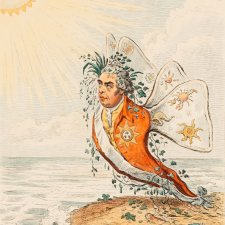

Wedgwood soon found the Sydney Cove clay to be “an excellent material for pottery”, and set about producing from it a small edition of commemorative medallions. The design was created by Wedgwood’s in-house draughtsman Henry Webber, brother of the artist John Webber who had sailed with Cook aboard the Endeavour, and the moulds were created by Wedgwood’s principal modeller William Hackwood. The heavily classicizing bas-relief composition was entitled “Hope encouraging Art and Labour, under the influence of Peace, to pursue the employments necessary to give security and happiness to an infant settlement”. This figure group on the recto carried the inscription “ETRURIA 1789”, and on the otherwise unadorned verso “MADE BY IOSIAH WEDGWOOD OF CLAY FROM SYDNEY COVE”. Thus the Sydney Cove Medallion is evidently the only work ever signed and dated by Wedgwood himself, a measure of the seriousness with which he undertook its manufacture. There does not appear to have been any sense of irony arising from the crazy disjunction between the allegorical subject and the harsh realities of Sydney Cove.

The first batch of finished medallions were sent to Phillip aboard the second fleet, which set sail on 19 January 1790, but Wedgwood also sent a specimen to his friend the midlands physician and intellectual Erasmus Darwin. Responding to Wedgwood’s invitation to compose some suitable accompanying verses, Darwin supplied thirteen couplets in iambic pentameter entitled “Visit of Hope to Sydney-Cove, near Botany-Bay”. These were in fact a slightly leaden pastiche of “Liberty”, by the Scottish poet James Thomson (who also wrote the lyrics to Thomas Arne’s “Rule Britannia!”). Together with an engraved vignette of Webber’s design, these appeared on the title page of final part of The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, with an account of the establishment of the colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, printed in London at the end of November 1789 by John Stockdale, sometime publisher to Dr. Samuel Johnson).

Any one of these stout warp threads of Enlightenment England – Banks, Wedgwood, the Webbers, Hackwood, Darwin, Thomson, Stockdale and, admittedly by very indirect association, Dr. Johnson – would be sufficient cause to celebrate this, the first British fabrication of a work of art using Australian raw materials. Being a set of multiples produced in the west midlands, moreover, it carries strong associations with the incipient Industrial Revolution. However, the additional Anglo-French, and even Aboriginal dimensions of the episode, to say nothing of the fact that in Sydney Cove dire necessity had been the mother of invention – all these converge on the medallion, and allow it to make the case, however illusory, that the first British settlement in New South Wales was indeed a project of the Enlightenment, and not merely the by-product of a cruel, corrupt and unwieldy eighteenth-century British criminal justice system, obsessed above all with relatively minor offenses against property.