Brilliant flecks of colour and smeared crusts of paint decorate the surface of Fred Williams’ paintings. Characteristically, these are landscapes. The organic filaments of dabbled, squeezed and flattened paint describe the jagged defiles and contoured edges of the Australian bush.

Williams posits visceral paint as living stone, dry rock, branches and leaf litter. His vision of the land, evoked with a distinctive fractured calligraphy, dominated landscape painting in Australia in the last decades of the twentieth century, supplanting Hans Heysen’s twisted ghost gums as the authorised version of our environment.

Williams’ portraits are not as well known as his landscapes, but are no less compelling. Fred Williams’ very first paintings were portraits and figure studies. His earliest known painting is a remarkably competent self portrait made in 1943 when he was fifteen, soon after he had left school to work as an apprentice shopfitter and while studying part time at the Gallery School in Melbourne. It was only after he returned from his studies at the Chelsea School of Art in London in 1957 that the landscape became the central subject of his art.

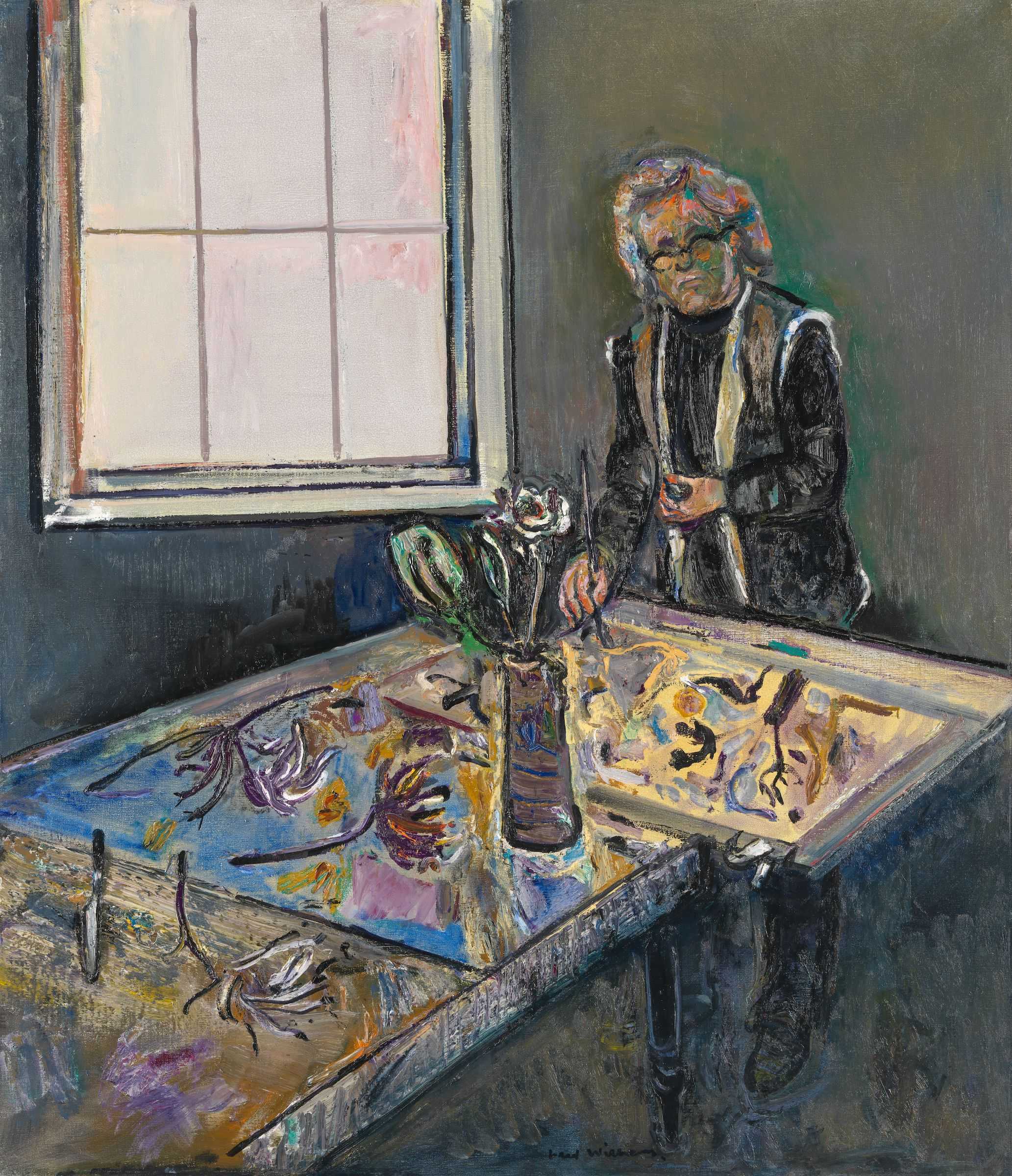

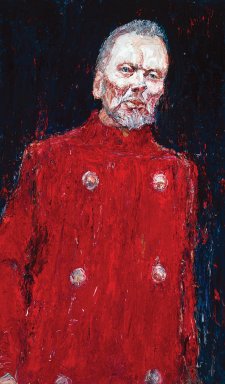

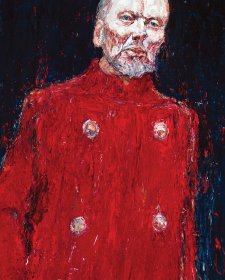

The National Portrait Gallery has six of Fred Williams’ portraits and one of them is an intriguing mix of landscape and portraiture. Clifton Pugh was a close friend. For a time Williams lived and worked at Pugh’s bushland retreat, Dunmoochin - perhaps the first artist commune in Australia. Picasso and particularly Kandinsky delighted and guided Pugh but ‘no Australian painters have influenced me’ he claimed in a 1988 interview, adding ‘I don’t think Fred Williams influenced me but every week we would paint together’. Clifton Pugh painting in the studio 1974 captures one such moment. Regardless of whether he was creating a landscape or a portrait, Williams employed a repertoire of sharp, calligraphic brushstrokes and a mix of thin and thick paint. Williams did not work from photographs. He sketched in the composition first then applied paint directly and vigorously – looking, then painting – matching image on canvas to image in the eye of the artist, all in a single campaign. As in his landscapes, he works a field of tactile paint and broken areas, creating a visual mesh that is bright and jazzy, to be melded by the viewer. The paintings that Pugh is working on in the portrait look for all the world like Fred Williams landscapes. This interior is something of a departure for Williams who favoured monolithic compositions, usually placing a single figure in the centre of the painting.

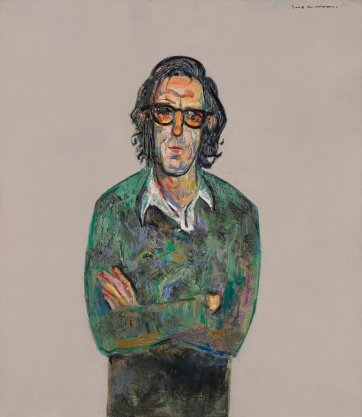

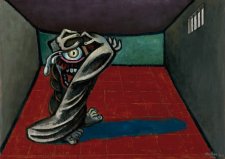

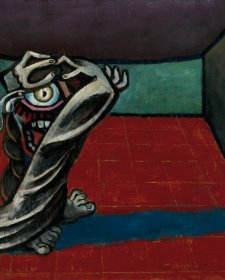

Within this formula there was room for play – as the portrait of artist-friend David Aspden, one of Australia’s foremost colour field painters, illustrates. The figure of Aspden confronts the viewer with its folded arms and bold, central position against a plain background. The success of the work derives from the tension of the continually tipping, just off-centre placement of the figure which is accentuated by the narrow El Greco-like attenuation of Aspden’s features.

When Pugh participated in the Antipodeans exhibition in 1959 with mutual friends John Brack, Charles Blackman and Arthur Boyd, Williams was not invited. The exhibition was intended to put emerging abstract art back in its place and demonstrate the importance of figurative art. Williams’ emphasis on the formal qualities of line and colour was suspiciously avant-garde and perhaps a touch too abstract. Ten years later in 1968, when Aspden showed in the influential Field exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, William’s predilection for landscape determined he was not abstract enough to be included.

Williams maintained a dynamic relationship between tradition and change, weaving a unique path that equivocally combined abstract forms and colour with representation. Characteristically, his portrait of David Aspden brings together flat, uninflected areas of colour with vigorous paint handling to meld realism and abstraction. Williams’ interest in the subject seems not as great as his interest in composition, the sitter’s personality is almost secondary to the powerful design. The pose is important - but less so for offering an insight into the sitter’s psychological make up and more to generate a striking composition. For Williams portraiture was inevitably a vehicle for paint. The overall impact as a work of art, landscape or portrait, was what mattered to him. The two friends were represented in the exhibition Ten Australians which toured Europe in 1974, just before this portrait was painted.

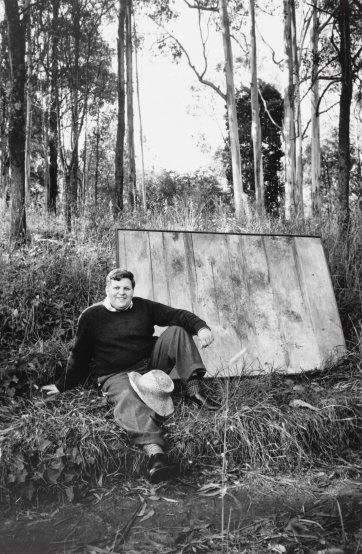

In 1974, Williams travelled to Erith Island in Bass Strait with Pugh and historian Ian Turner and writer Stephen Murray-Smith who was researching the peoples of the Bass Strait islands. It was there that Williams developed his ‘strip’ paintings: panoramic littoral views where sea meets land and earth meets sky. Founder of the literary magazine Overland in 1954, Murray-Smith was an extremely influential figure in Australian culture. Like Turner, who also wrote for Overland, Murray-Smith was a committed socialist and both used the journal to critique contemporary Australian society. Pugh, Turner and Murray-Smith had all served in New Guinea and the war shaped their view of the world. Postwar, Turner and Murray-Smith had joined the Communist Party but later drifted away disenchanted in the early fifties, adopting, like Pugh, the broader platform of the Australian Labor Party to effect change. Williams, as always, maintained a left-leaning but independent position. Overland’s motto, ‘Temper, democratic; Bias, Australian’ suited him fine.

When Williams painted the portrait of Stephen Murray-Smith in 1980, he upheld a similar contract of modernist dispassion and singular observation just as he had earlier with Aspden. Murray-Smith’s figure dominates the composition, looming against a neutral ground of pale grey-blue paint. Williams’ old friend has a philosophic air about him with his pipe and thoughtful profile. His jumper is as craggy as any landscape that Williams might have painted, corrugated and cracked, moss covered and variegated as a Bass Strait island.

Williams didn’t pursue commissions. His portraits reflect his connections and friendships. The portraits of Pugh, Aspden and Murray-Smith were given to the Portrait Gallery by Lyn Williams this year. They join the portraits of Murray Bail, a gift of an anonymous donor, and Harold 'Hal' Hattam, obstetrician, artist and art collector, a gift of the Hattam family in memory of Hal and Kate Hattam, and the artist’s last self portrait already in the collection also a gift of Lyn Williams. William’s skill in portraiture was as singular as his flair for landscape. He created a new way to depict and envisage the Australian landscape, developing a vocabulary of jabbing strokes and terse curves,blobs blotches and agitated mark making which he combined with broad swathes of colour. He applied this approach to his portraits, using his vivid notations to depict his people, his landscapes, his world.

Fred Williams’ 1960-61 self portrait and the stunning portrait of writer Murray Bail are part of the exhibition Fred Williams: Infinite horizons at the National Gallery of Australia from 12 August to 6 November 2011. In conjunction with Infinite horizons and to extend an understanding of Williams’ contribution to Australian portraiture, the Portrait Gallery is displaying the newly acquired portraits, generously donated by Lyn Williams.