The boy who was to become the aircraft designer, pilot and entrepreneur Sir Lawrence Wackett kbe dfc afc (1896–1982) grew up in the Townsville suburb of Hermit Park. As an adolescent, he made some model aircraft out of unviable materials, and some successful hot-air balloons, but as he remembered it, such activities were at odds with the inclinations of the other boys of the neighbourhood, and only confirmed his reputation as a crank.

Fatherless from the age of six, he was educated at Mundingburra State School, with a brief, unsatisfying interlude as a scholarship boy at Townsville Grammar; he laboured at an ice-works and did odd carpentry jobs to save money before taking up a scholarship to Duntroon in early 1913. He was the only shivering Queenslander at the isolated military college, which struck him as equally suitable for a penitentiary or monastery. On their first day he and his classmates – who comprised the third intake of cadets – watched the laying of the foundation stones of Canberra.

The Wright brothers first flew in North Carolina in December 1903. International escapologist Harry Houdini made the first officiallyrecorded controlled powered flight in Australia in Victoria in March 1910.

Hudson Fysh, founder of qantas, first sighted an aircraft in Geelong four years after that. Although international arms manufacturers quickened to its potential, it is unsurprising – however extraordinary in hindsight – that not once during the officer training course Lawrence Wackett undertook from 1913 onward was the aeroplane taken into consideration as a possible instrument of war. Furthermore, he recalled, ‘not a single piece’ of radio apparatus was amongst the instructional equipment at Duntroon. Once or twice during tactical debates Wackett suggested possible impacts of aeroplanes on warcraft, but found that the conversation hastened on. Making friends with the college carpenter, he pressed on with his inventing, creating an electrical signalling system between rooms of the college and, more significantly, a successful automatic fuse setter for rapid-firing guns (though the Army was not prepared to adopt it, after the war the remarkable device secured his entry to third-year science at Melbourne University, whence he graduated after eight months’ study). Wackett recalled that proud as he always remained to have been a Duntrooner, he was ‘as far from being a typical Duntrooner as it would be possible to find.’

Having elected to graduate as an artillery officer rather than join the infantry or light horse, no sooner had Wackett had arrived in Melbourne for artillery training than he answered a call for pilots to train at Point Cook, southeast of Melbourne, ‘no more than the nucleus of a flying school’ as he described it, but Australia’s sole air arm in 1915. The afc’s No 1 Squadron was formed in January 1916. Sent to Suez, Wackett flew reconnaissance over the Sinai Peninsula. The engines of the planes were sorely affected by the heat; carrying two men, lugging a machine-gun, four 25-pound bombs and sufficient fuel for four hours, the planes would ‘literally stagger into the air’, he wrote. For weeks on end he went out every day, machine gunning, bombing and taking thousands of photographs. Hudson Fysh arrived in the Middle East just as Wackett was leaving for France, but he nonetheless remembered Wackett as ‘that great old No 1 Squadron afc character, inventor, mathematician, engineer and general enthusiast.’ Indeed, when Wackett heard about an enemy monoplane apparently fitted with a machine gun timed to fire through its propeller, he resolved to develop a synchronised machine gun to fit one of his own squadron’s planes. ‘Within a week I was ready, having worked with simple tools that were available – a vice, breast drill, hacksaws, files, oxy-welding set, etc., plus some parts of a Singer sewing machine which I bought from a Singer agency in Port Said’, he recalled. After a farcical first try, the young inventor made some simple adjustments – and it worked.

In 1917 Wackett was sent to Orfordness Experimental Station, the technical development organisation of the Air Ministry in Suffolk. It was an environment in which everyone was an expert, swarming with men who would progress to the highest posts in the technical branch of aeronautics.

In Egypt, Wackett confessed to having hesitated to mention anything that would result in his being considered ‘highbrow’, but at Orfordness he felt the strain of holding his own in brilliant conversation. Furthermore, ‘in contrast to the life at Duntroon of two years ago where any suggestion that there might be a better way of doing things was immediately suppressed, at Orfordness it was a much as one could to to keep up with the forward thinking … When, after living with this brilliant band of Englishmen, I returned to an Australian unit, I was careful not to make it obvious that I felt a difference in the standard of mental alertness.’

Arriving in Europe in the spring of 1918, the Queenslander was soon to play a vital role in two turning points of World War I. The first was the upshot of a personal approach by John Monash, who had heard tell of his ingenuity and asked him if it would be possible for him to devise a system to convey ammunition by air to troops in the front line of battle.

Within days, Wackett had devised and demonstrated a bullet delivery system and secured the men and equipment necessary for its manufacture. In a converted hangar, his gang hammered, sewed and welded night and day to produce parachutes attached to wooden boxes crammed with ammunition. Just weeks after Monash’s request, Wackett reported that he was ready to deposit 200 000 rounds of ammunition at 24 hours’ notice. Monash’s first great military success, the Battle of Hamel, was won in July 1918 with Wackett pinpointing positions and dropping supplies using the system he invented; the first outstanding British victory since the Germans had reached Villers- Bretonneux, the battle marked the beginning of the Allies’ final push to victory. Monash devoted two pages of his The Australian Victories in France in 1918 to Wackett’s leading part in the Hamel drama.

Secondly, Wackett was a key figure in the dismantling of the Hindenburg line in September-October 1918. The German support line, where most troops were stationed, was ten miles behind the Hindenburg trenches, but its defences and weaknesses were uncertain. Wackett was singled out to fly the lone plane from which photographs of the entire line would be taken. Obliged to maintain a height of no more than 500 feet, he knew that every gun in the region would be firing on him and his observer, ‘but I had heard of others surviving such risks’, he wrote. Wackett’s account of the flight incorporates all the nailbiting elements of early air adventure stories: the deafening burst of shells around the frail fuselage, the tracer bullets streaming above and below, the splatter of bleeding engine oil and water. He landed in allied territory just as his propeller seized, walking away from an aircraft shattered by bullet holes and shell fragments. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross immediately, and the Air Force Cross a few weeks later; he had already been Mentioned in Despatches. He was just twenty-three.

After the war, Wackett went to work at the raaf Experimental Station aircraft workshops at Point Cook. In 1924, he designed the fragile Warbler, powered by an engine that he had also invented, the Wizard; it was soon followed by the Widgeon flying-boat, in several incarnations, and the Warrigal I and II landplanes, the latter the first all-metal aircraft to be built in Australia. In the early 1930s he designed the Codock aircraft for Charles Kingsford Smith, who became a close friend. By 1936 the Codock had evolved into the ljw7 Gannet, manufactured by Tugan Aircraft.

In the early 1930s, as tension increased between China and Japan, the leading industrialist Essington Lewis provided alarming first hand reports on the expansion of Japanese manufacturing. Spurred by Lewis, the Australian government recognised the need to establish a domestic aircraft industry. The industrialist WS Robinson recommended the establishment of the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation, a joint venture of six large companies including bhp; Essington Lewis’s close friend Harold Darling was its inaugural chairman. As head of the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation from its formation in 1936, Wackett was sent to investigate the aircraft factories of England, Europe and the usa. He and two fellow engineers were disconcerted by the aggressive salesmanship of the Dutch, depressed by the impotence of brilliant French engineers constrained to work in a nationalised industry, impressed by the efficiency of Prague’s Walter Werke. However, it was in Germany – the people of which were good-looking, orderly and cheerful and the countryside of which ‘gave no indication that World War II was only three years away’ – that they were profoundly shaken. At the Junkers works in Dessau, where the Nazi guards were courteous and their guide, who had lived for a time in Australia, spoke perfect English, Wackett and his colleagues were ‘staggered by the potential’ of what they were looking at: ‘No where else, in England, Holland or France, had we seen anything to approach these establishments. They were new and modern in every way.

The engineering technique was superior to anything we had seen in England... I predicted there and then that the situation could be interpreted that Germany would not be ready to start a war for about two years, but it was very likely to start then because of the marked advantage Germany would have … If the production of armaments generally was being organised on efficient lines comparable with what had been done in aircraft production, then Germany was indeed a menace … If we were to achieve anything worth while in Australia we must do it in the next three years. I resolved to convince the syndicate and the Air Force of this belief. We actually reached the production stage in Australia in two-and-a-half years, the first Wirraway flying on 27 March 1939. We had therefore accomplished something before war broke out in September. This was, in my opinion, the most important achivement of my life’.

The production of the Wirraway, a monoplane based on an American design, was spearheaded by Wackett at a new factory at Fisherman’s Bend, Port Melbourne, in 1938-1939. Eventually more than 700 Wirraways were produced. Later, for the Empire Air Training Scheme, 200 units of the simpler Wackett Trainer were produced to prepare pilots to fly the Wirraway.

The Boomerang, a plane Wackett designed with the German-trained Austrian Jewish engineer Fred David, was the first Australian-built combat aircraft. Later, Mustangs, Sabres and Mirages were also produced under license at cac. W Robinson wrote that ‘it was something of an achievement that our aircraft plant was mass producing aircraft in Australia long before any plant was mass producing cars. Furthermore, when war did come, it was in a position to give grand service to Australia in producing training planes and dive bombers.’ Soon after Essington Lewis became head of the Department of Munitions in 1940, he appointed his friend ‘Wack’ as an adviser.

In 1919 Wackett had married Letitia Wood, a remarkably pretty woman whom he had discreetly admired at Mundingburra School and got to know on a ship to Townsville. Their son Wilbur, the first Australian to shoot down a Japanese aircraft, was declared missing in action in New Guinea in 1944. My Hobby is Trout Fishing (1946), one of Wackett’s two books on fishing, was dedicated to his lost boy. Studies of an Angler (1950), including an affecting poem about the family’s times together on the Tyers river, was dedicated to Lady Wackett: ‘I dedicate this book to my dear wife / Letitia / who approaches very closely to the ideal angler’s wife. Although having no desire to fish herself, she has always taken a keen interest in my hobby. She likes to come camping with me, and is very fond of trout, which she cooks particularly well. I have never been begrudged the time necessary to enjoy my fishing.’

Not only did Wackett manage to sideline the demands of his career to angle on weekends, by night he also developed into a renowned exponent of the feathered fly. Hudson Fysh related in his own Round a bend in the stream how he bagged a wily cruiser at Bolero on the Murrumbidgee with a prized Orange Wasp tied ‘magnificently’ by Wackett.

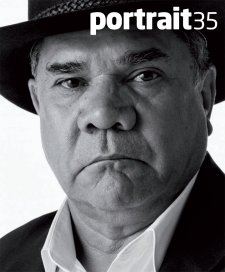

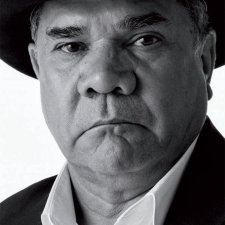

In 1954 Wackett was knighted for his services to aviation and in 1974 – by which time he had been severely disabled by a domestic accident – he received Australia’s highest aviation honour, the Oswald Watt Gold Medal. His farewell function from the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation was attended by 3 000 employees, most of them familiar faces to the man who had spent five hours a day on the factory floor throughout his years as manager. At that affair, Essington Lewis presented him with this portrait, which was subscribed by the employees.

The portrait of Lawrence Wackett is the sixteenth in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection of works by William Dargie, which includes paintings of Wackett’s friends Essington Lewis and Harold Darling. Although on first glance the portrait seems conventional (the more so because of the frame, which is curiously atypical of 1959) Dargie has painted Wackett in somewhat eccentric perspective. He sits in a boardroom or drawing-room chair, but he is in fact in the open air; the façade of the cac’s main building, in which his office was actually located, is below him on the right. (The building now houses rmit’s Sir Lawrence Wackett Centre for Aerospace Design Technology.)

The portrait, which passed to Wackett’s daughter Arlette when Lady Wackett died, has hung in the home of Wackett’s grandson Roger Perkins for many years. The family has always liked the portrait; to them it seems a subtle representation of Wackett’s demanding, authoritative yet compassionate personality. A valuable addition to the Gallery’s strong holdings of portraits of key figures in Australian aviation, it will reunite Wackett with others who served Australia through the world wars and regrouped to forge and drive its prosperity in the ensuing decades.