The exhibition illustrates a broad cross-section of men and women from across Australia working in a variety of styles, from abstraction to the most exacting realism as well as traditional Aboriginal painters. R. Ian Lloyd examines through these large photographic portraits the individual artist's working environment: whether it be an inner city loft, a kitchen table or the sandy earth of the Outback.

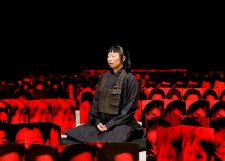

In search of the meaning of creativity Ian Lloyd points his camera in three directions. He makes portraits of artists, he focuses in on the tools and materials of their art and he captures them in the theatre of creative action - the studio. Among these three approaches portraiture, paradoxically, is the least revealing, since the physiognomy of the artist reveals little about his or her work. The hands of the artist, gripping brushes and working paint on the palette yield more understanding. Yet it is the studio and the artist at work within it that provides the greatest insights into the nature of the creative act.

The studio is a kind of laboratory, a place for process. Undeniably, the products of the studio are more important than the studio itself or how it looks. Indeed some of the most significant Australian painting has been produced outside of the studio. A room of one's own is not, therefore, a precondition for creativity. Nonetheless, as Lloyd's photographs attest, there is a close relationship between an artist's work and the environment in which it is produced. It is this relationship that makes these photographs so engaging. They raise the question as to whether the artist creates the studio or the studio creates the artist.

Artists' studios are generally private places and their owners are selective about whom they choose to invite. Through his photographs, Ian Lloyd offers us the rare privilege of entering the private spaces of many significant Australian painters.

Lloyd's work is part of a 20th century phenomenon in which the previously unseen world of painterly processes is revealed through photographs. Perhaps the best exemplar was Alexander Liberman's book, The Artist in his Studio (1960). But looking back on that project half a century later, one is struck by the monumental stasis that characterises its approach. Most of the artists photographed by Liberman were grand old men of modernism, seemingly content to sit among their life's work and chat with their visitor. There is a disengagement from the actual activity of producing art.

Painters have been depicting themselves or their friends in studio settings since the time of Velasquez, but it was only in the 19th-century that the studio came into its own as a subject. Painting developed a fascination with its own condition and artists tended to depict the intimate, often solitary side of studio life. In photographs, on the other hand, many late 19th-century studios display a public character sometimes reaching the scale of a factory or a salon. These large-scale studios were not only places of work but of social interaction. Nowadays there are few examples in Australia of the studio as semi-public place, a setting for parties and conversation, such as Thea Proctor's Sydney studio of the 1920s or Brett Whiteley's now memorialised inner-city studio.

One of the most compelling aspects of Lloyd's photographs is the great mass of detailed information they contain. This leads to a number of observations about the relationship between artists and their studios. Firstly, we become aware of the way in which the world of colour, light and subject seems to be compressed into a single space, and the continuum between these conditions and the works of art that are produced. Two examples - Robert Hannaford's studio and Marion Borgelt's - will illustrate the point. The chocolate and honey tones of Hannaford's paintings are echoed in the brown leather and wood of the studio furnishings. Similarly, the precise geometric aesthetic of Borgelt's work inhabits a space of clinical austerity. In many of the studios there is an intriguing coincidence between detritus (paint rags, drop cloths, caked floorboards) and works of art. We are left with a compelling realisation of the materiality, the physical presence of art objects. We are reminded that, above all, art is the transformation of material - it is something made.

Secondly, Lloyd's photographs reveal the way in which painters see themselves, consciously or otherwise, as having a connection to the traditions of painting. On the walls of many studios one finds postcards, photographs and magazine clippings reproducing the work of earlier painters. Art books litter the floor or lie open on tables and shelves. Whilst it would be wrong to draw superficial conclusions about 'influence' from such inclusions, it is reasonable to observe how consistently artists use the art of the past to inform present practice. This is also true of indigenous artists, with one significant difference: these artists are clearly less dependant on cues from reproduced imagery than on sets of internalised visual prototypes.

Thirdly, not only do we search the studio shelves and walls for insights into painting, but with so much detail on offer we hunt for clues by which we might better understand the personality and character of the artist. As Rothko observed, all painting is portraiture. And, in a way, all studios are portraits, sometimes consciously constructed self-portraits. They cannot help but be a kind of psycho-space from which we gain information, perhaps confirming our preconceptions about a particular artist.

But although the studio may act as a portrait in its own right, it is the living presence of the artist that provides its specific meaning and dynamism. If the artist is not present we sense a powerful absence. When important artists die their studios are occasionally preserved intact, yet such acts of well-meaning posterity usually fail. Without the active presence of the artist such places are depressing. Take, for instance, the studio of Norman Lindsay - a poignant relic of a failed Arcadian dream, a strange, hollow experience without the obsessed and driven creator at its core

It is the work of the photographer to arrest time, too, but to better effect than the studio-preservers. We may feel privileged, through photography, to enter into the private worlds of artists at a particular and precise moment in our art history. We know there is a before and an after. It is reassuring to know that all of the studios recorded here have changed. They began to change the moment the photographer left - new works have been made, paintings have come and gone, styles have shifted, new mediums and ways of working have been discovered. In these photographs Ian Lloyd has revealed something living - the constant interaction between artists and the material world that is the essence of the creative transformation we know as art.

Andrew Sayers

Director,

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra