Hall of Mirrors: Anne Zahalka Portraits 1987-2007 explores the thread of portraiture through the artist's prolific career, now spanning more than 20 years. Tampering with truth in representation, blurring the boundary between reality and fiction, Zahalka uses a variety of photo-media techniques. Incorporating photomontage, double exposure and darkroom trickery in her early images, she embraced Photoshop soon after its inception in 1990. Her practice has consistently enquired into the nature of image making and its relationship to the world around us. Through an assemblage of cultural symbols and art-historical references, Zahalka questions what a portrait can actually tell us about someone, and highlights photography's ability to command, distort or deny the truth. With acute observation and an ironic voice, Zahalka cleverly subverts stereotypes, capturing subcultures and a spirit of the times.

Naomi Cass, Director of the Centre of Contemporary Photography, in conversation with Anne Zahalka

While much of your work is peopled, not all of your work is portraiture. How would you distinguish between a photograph with people and a portrait?

It's difficult to distinguish today between a portrait and a photograph of a person. The lines have been blurred - anything can pass for a portrait if the artist says it's one.

Traditionally portraiture has been subject to a number of strict conditions that artists adhered to. It was usually made as an image of pride and projected certain ideas about the sitter. A portrait made of a group or of an individual attempts to define the sitter(s) - who they are and what they represent. In the works of mine you are referring to, I am not primarily interested in the individual but more with what they represent. For example, my portrait of The lifesaver is not about who he is, but rather what he stands for as a sign of Australian masculinity and as a symbol of the beach or even of the nation. I don't consider this to be a portrait but rather it represents a type. In other works I may provide a generic title such as 'artist' and in brackets their name. This is to emphasise that it is the figure of the artist with which I am primarily concerned. In the series Resemblance, the titles are generic, such as The cook, The cleaner, The writer, and in brackets I have included their name and occupation. In some cases it supports the role they are playing and in others not. In this way it raises questions about the very nature of portraiture - when is a picture of someone a portrait and what is it that defines it as such?

Can you speak about the idea that the function of portraiture is to capture the inner life of the subject, indeed that it is possible for an artist, particularly a photographic artist to capture what lies beneath superficial appearances, namely the essence of the sitter?

I am deeply cynical about the idea that a portrait can reveal or capture the inner life of a subject. I want to raise questions about what portraits mean and what are the conventions governing them. My earlier approaches to portraiture were informed by postmodernism and led to a questioning of representations and historical conventions. I constructed my photographs so that the sitter is arranged in, or against a setting that provides a context for them. Surrounded by possessions, or against a location they are purposefully placed, it is a way of building up meaning about them. In a photo shoot many expressions pass across the sitter's face and only one image is selected to stand in for all. Sometimes there may be an expression captured that does suggest something deeper, but it is the viewer who interprets this. We project onto portraits what we want to see. There is no intention on my part to persuade the viewer they are being shown anything deeper than what lies on the photographic surface.

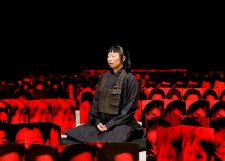

Your portraits look quite performative. For example, none of your subjects are smiling, although none appear unhappy. What is the role of performance in your work and your role in establishing this performance?

I encourage my subjects to perform themselves playing a role. Often we are self-conscious when the camera is turned on us - how do we want to appear, what do we want to project? It's easier to play a role rather than try to appear oneself. We can assume an identity, put on a mask and perform ourselves acting a part. It's also easier for me to direct a person when they feel they are playing a role. If I want them to look heroic, proud, contemplative or preoccupied they are assuming the part. For example, in my photograph of three Burqini-clad Muslim girls they take up a strong, almost masculine pose whilst mimicking the stance of lifesavers or guardians of morality on the beach. Their expressions are a mask of this position.

In Charles Meere's idealised and celebratory painting of the beach, no one is smiling, although they look like they are having fun in a contrived way. My multicultural group, based on the same image, appear happily content to be sharing close quarters with others on one of our most contested national sites - the beach. They perform the same exaggerated gestures in an ironic way to assert their right to be there and to belong.

Some of my sitters have asked why I won't let them smile in their photograph. For me it doesn't make sense to be smiling - what are they smiling about? Traditionally, in painted portraits people are rarely shown smiling, so why should a photographic portrait depict the sitter smiling. It's complicated by the fact that photographs depict moments and can capture people in a spontaneous and natural way. But within a formal portrait it becomes more about this moment captured and preserved for others to see.

In Resemblance you have created elaborate settings for your sitters, replete with quotations from seventeenth-century Northern European painting. Indeed, there is much pleasure in examining these works for their literate references. However, the series is far from a slavish impersonation of the past, playful conceits and contemporary references also abound. Is this series an homage to the past?

I have a deep affection and admiration for these paintings from the past. They are embedded in my cultural memory and are part of my history. I have grown up with these works through the institutions I attended and they resonate strongly with me. I also studied them in secondary school and later re-read them through the discourse of postmodernism and the writings of Svetlana Alpers in The Art of Describing, Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, amongst others. Many of these influences have informed the making of this work and I should pay homage to them all. The works of Vermeer continue to be studied, analysed, copied, written, are the subject of films and continue to be adored by audiences everywhere.

For me it is the camera that bears witness to what lies before the lens and what painters painstakingly struggled to capture. It is its ability to record the surface of things, capture light, delineate textures and draw faces seamlessly, all filtered through the lens. But it is the painter's way of seeing and organising pictorial space that has provided the greatest influence and to whom I am most indebted.

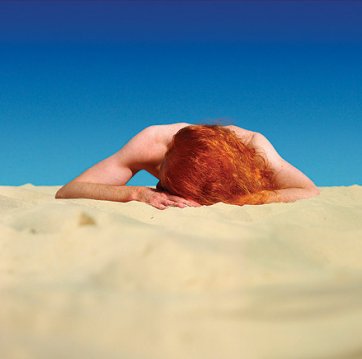

In thinking about Resemblance where, it seems, as much can be learnt about the sitter from his or her surroundings as from their physiognomy, what are you saying about the ability of the camera to capture a portrait? Can you speak about the series Gesture, where surprisingly the face has been removed?

My Gesture series was made through scanning and erasing details of paintings from the canons of portraiture. Within portraiture the face has always been a privileged signifier of the soul, spirit and personality. By denying the significance of the face through its erasure, I wanted to show how the body, hands and objects continue to project character, power and meaning. This involved a stripping away so that the gesture might exist as a 'sign'. These transplanted gestures retain their meaning in submerged and hidden ways. The disembodied hands riven from the gesturing subject enable an intervention with history and its representations in order to examine the codes by which identity, status, power, wealth and gender are defined. The erasure of the face allows the gesturing body to speak.