Since establishing the artists' community, 'Dunmoochin' in the 1950s Clifton Pugh became known as both a landscape and portrait artist, yet it was Pugh's portrait painting that drew consistent attention, with his innate knack of capturing the character of a sitter. His popularity and reputation as a portrait painter was secured by winning the Archibald Prize on three occasions, in 1965, 1971 and 1972. The exhibition will demonstrate Pugh's valuable contribution over 36 years to the genre of portraiture in this country.

In 1970, when Clifton Pugh was forty-five, the British Council held a retrospective of his work in London. This followed the National Gallery of Victoria's exhibition of his portraits, celebrating the publication in 1968 of Andrew Grimwade’s Involvement, which lavish book reproduced all but one of the portraits to that date. Clif went to London for the retrospective, taking a show to André Kalman’s gallery. He spent time in the London galleries, his first direct experience of the masterpieces there collected, visited historic houses and collections in the country. He went to Paris, studying etching with Hayter, before returning to Australia in August 1970.

After leaving school at fourteen during the depression when his father died, he had worked as a draughtsman. Joining the army in 1942, he fought in terrible conditions in New Guinea, killed in hand to hand combat, was wounded by a grenade, contracted malaria and dengue fever. But Clif painted when he could, and as a forward scout, drew indigenous birds for ornithologist Captain Jock Marshall. He was posted to Kure, near Hiroshima, with the occupying forces. What he saw in Hiroshima and elsewhere in post-war Japan, together with his wartime experiences, not only informed his ideas about humanity but drove him to express them through art.

His post war study at the school at the National Gallery of Victoria was funded by the Commonwealth Reconstruction Scheme. There, Sir William Dargie taught tonal impressionism. This technique, as often as not producing portraits which Geoffrey Dutton wonderfully describes as “still life with human features” Clif found constraining for portraiture and landscape. He had come to the gallery inspired by the ideas of Kandinsky and the expressionists; to learn about materials and method, and to ground his drawing skills, formerly turned to draughting and science, not expression of artistic ideas.

When Clif left the school in 1951, the European pilgrimage did not appeal. His first marriage had ended; he wanted stability, to find his way in painting. He settled twenty miles north of Melbourne, near the valley where he’d spent contented early teenage years, building a mud brick house and studio. He spent a year hardly painting, just wandering through the delicate bush, learning how its greys are made of subtle gradations of blues, pinks, and yellows: how the intricate pattern of life of tiny insects, of birds and animals, mimics our own. The harsh memories of the war and the ordeal of the Japanese people, the embodiment of these experiences through injury and illness and direct observation, he had understood through the words of artists and poets. Now these memories wove into the subtle lacy texture of Dunmoochin bushland, and the vivid imported patterns and colours of its surrounding pastures.

In 1954 he travelled across the Nullarbor. His friend Noel Macainsh, painted as “A Poet in a Landscape” accompanied Clif to the desert on more than one occasion. “…the sense of sheer immensity, the boundless extent of a land, paradoxically both harsh and delicate, together with the illimitable space above it”. Responding to the desert, Clif found a way to express his ideas about humanity, spirituality, and art. He could now place his experiences into time, into more than history, and, through this, objectify and share them.

He began to develop a distinctive style, combining expressionism with the tonal impressionism with which he’d been burdened, introducing abstract elements both in portraiture and landscape. Only on rare occasions did he bring the human figure into the landscapes. The first was a series of paintings of St Francis in the Australian desert, responding to the place of aboriginal people the outback; and, after a time in Mexico with his second wife Marlene and their sons Shane and Dailan, the Penitents series.

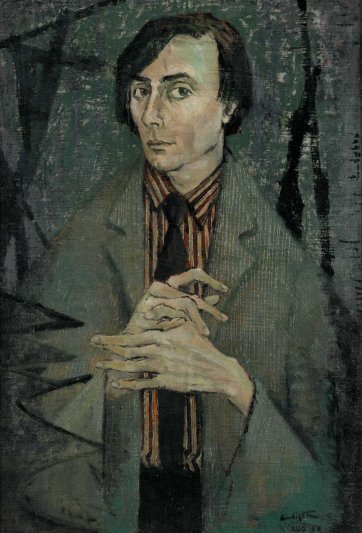

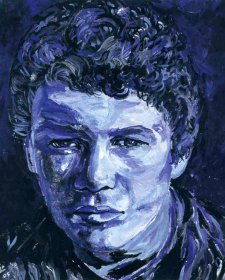

Pat Tozer, Portrait of a Painter (Kevin Meynell), Kate Hattam, The Muse and Ourselves, The World of Shane & Dailan. These paintings are of companions and of family: the ‘50s and early 1960’s were a time before fame, not only for Clif but his friends. Tom Sanders, Barry Humphries, Margot Knox, Peter O’Shaughnessy, David Armstrong, Noel Macainsh, would become known in their various fields. Then, they lent their images to experimentation in portraiture. Gaining confidence in his capacity to get a likeness, Clif practised the balance between personality and physical characteristic, between art and representation. He began to use elongated forms, curves encircling the body, shapes and patterns that imply forces outside the sitters, to form their personalities.

The artworld was about class, then: bohemia meeting money old and new. Clif’s father had been a working gentleman, his maternal grandfather was government astronomer in Perth and Sydney. Active army service of itself would have paved the way in that world, and Clif was extraordinarily astute at judging and responding to people. He was involved briefly in The Contemporary Arts Society, but was not in artworld politics, on boards or lobbying for particular people to be appointed to positions of influence. However, his hatred of war meant that when Clyde Holding, leader of the opposition in the Victorian Parliament, asked him to chair a policy committee on the arts for the ALP, Clif agreed, hoping it might help elect Labor and hasten the end of Australian Vietnam involvement.

Although he won the 1965 Archibald Prize, the landscapes as much as his portraits made his reputation in the artworld, through group shows with the Group of Four and the Antipodeans, annual solo shows in Melbourne, at the Johnstone Gallery in Brisbane and with Sydney’s Rudy Komon. He had considerable support from the Australian art establishment. He won the Maude Vizard-Wholohan, and The Crouch Prize, and was included in prizes such as the Rubinstein, the Georges and official exhibitions which travelled to New Zealand, Japan, to the Whitechapel Gallery and the Tate in London, to San Francisco, Los Angeles, Washington and St Louis, USA, to Montreal, Canada. By 1970 his work was in all State galleries, Regional Galleries, and the National Collection.

He went straight to his beloved desert from Paris: on his return to Melbourne, after the second Vietnam moratorium march, went to a party; and there we met. It was psychologically a triumphant return. Marlene and he had separated before he left for London, and were now apart on good terms. Each London exhibition had been a critical success, and the Kalman show sold, as did a double portrait of Kit and Patsy Dawnay, he the chairman of Dalgety’s. The Involvement exhibition and the retrospective had given Clif opportunities to reflect on his work, and this was followed by absorption in the impressionists and moderns in Paris. He’d enjoyed contact with other international artists at the Cité and at Hayter’s studio, the moratorium gave hope that the Australian political mood would change. He had money in the bank. For the first time since leaving the beloved childhood valley he was returning with an international reputation as one of Australia’s major contemporary painters; secure, to comfort, to the known.

Clif never liked to live off capital: there was always the anxiety, as there is for most artists, that he might fall out of favour and have no income. He was not a prolific painter, and had been buying back what early work he could. The gouaches painted on his recent desert trip would sell easily, but he wanted them around him while the work he’d seen in London and Paris simmered in his unconscious.

All that summer, Clif kept talking about the way in which Bonnard, Matisse and their contemporaries painted: “The water flows up hill and it doesn’t matter”. . .

He was in the studio each morning, just sorting through things, preparing boards, looking at photographs and books, bringing records up to date. With Frank Hodgkinson, John Olsen, Fred Williams, whoever was about, he went out painting at least once a week. There was regularly a model, drawing was a continuing discipline for Clif, Bert Tucker and other painters who lived nearby. Gouaches were a step on the way, plein air records of the moment: responses to light, colour, perspective; the feel of a place. He was not ready to begin painting in the studio: that is, to make statements, images in oil on board, where ideas about society met ideas about art.

He had a couple of portraits to paint. After having to deliver the first commissioned portrait of Viscount de L’Isle, despite being unhappy with the painting, he did not take commissions, instead offering to “have a go”. If the person liked the painting, they had first option on it but were not obliged to buy, and crucially, Clif was not obliged to sell. The second painting of de L’Isle, painted at Dunmoochin instead of the formal scene at Yarralumla, became the official portrait. De L’Isle is stiff, it depicts an awkwardness, courtesy covering shyness, a kindly man compelled to be official.

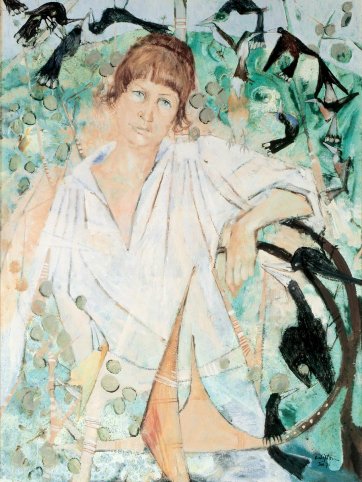

Clif wanted to do these portraits to get back in the rhythm of painting. To that time, my time as it were, he had not had a consistent companion to occupy his subjects and free him to paint. “Would I talk to clients while he painted?” “Yes, I would”. “Good”. This would make the task easier. Thus the story of our marriage was framed by portraits.

He had spent his early teens in country outside Melbourne, had been out in the world working, joined the army as a young man, had lived hard in the jungle, and fought in hand to hand combat. Country people judge a person on looks, on expression, as one does in the workplace; and a soldier in close combat must rapidly assess his protagonist’s expression. This background made Clif a formidable and very conscious judge of character. On the street, in restaurants, in aeroplanes, as we arrived at parties, in the car: “Look at him. I wouldn’t trust him”. “His face is kind”. “He is guarded, what’s he hiding?” “He is too much of an academic”. “She is good”. “He would be a tough negotiator”. “She is scheming”.

Of his dealer Rudy Komon “He tries to be very cynical, but he is a bit too honest and he can’t quite carry off the attitude he would like. He would like to think of himself as being the “smart boy” but I don’t think he can, because he loves the good things in life a bit too much.” Rudy and such supporters as Andrew Grimwade had arranged for Clif to paint portraits from the early 1960’s and the experience of portraiture of course improved his capacity to read faces.

Subjects who started as strangers often became friends. The line blurred too, because the Australian art scene was small in those days. Doug Carnegie, Andrew Grimwade, Geoffrey Dutton, Harold Holt, were painted as much as friends as public figures: the Holt portrait in particular gives flavour to the period. Clif was to skin dive with Holt the day Holt died, but 17th December was Clif’s birthday and it turned out there was party planned, so he cancelled the arrangement. Ah, Australia: an artist absolutely opposed to his policies, skin-diving with and painting the Prime Minister, putting him in op-art pants, on a long, hot, January holiday.

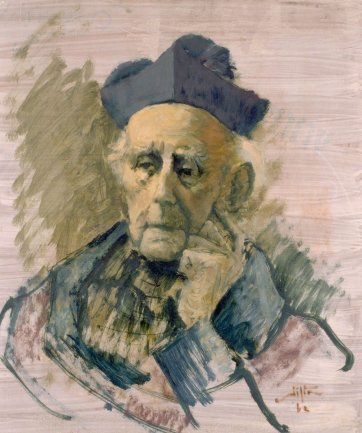

He became more confident once he realised that these men of the world were more nervous than he in the portrait relationship. The more he responds to them, the more interesting the painting: when the person is very vivid, very charismatic, the more he concentrates on hands and face as expression of individual character in society. The engagement in the early period with Rupert “Rags” Henderson, Mannix and Coombs in particular began an exploration about power that was to develop in the 1970’s.

Clif still painted his friends, and the portraits of Marlene, together with the self portraits, trace their marriage through the 1960’s. In 1967 he sketched, almost more than painted, the magnificently ironic David Tolley & Family, challenging the convention of portraiture, anticipating 1970’s feminism and celebrating the feminine.

I too was sitter, as well as interlocutor. It was easy to be still at a moment when he was looking closely, as if at the hairdresser without the chatter. I thought my portraits were exercises, the relationship secondary. The retrospectives gave Clif confidence that he could express ideas and emotions; Paris meant that the subtlety of paint had become the challenge and a pleasure. And I was the constant image in place and season, an essay in the relativity of light and colour.

From the early lean years he’d used masonite, composition board in formal catalogue terms, bought from the local garage/hardware store: it was much cheaper than canvas. It became his familiar preferred material even with money at hand. He prepared a number of boards at a time with creamy-white. He began a portrait, indeed, any oil painting, by working directly onto a prepared board on an easel set up in the studio, with the sitter in front of him. He would work on the painting between sittings.

Clif used his memory. He sometimes made sketches in gouache or oil, but not as preparation for a painting. He very rarely drew a portrait subject in pencil or pen, and then only if the drawing was of itself interesting, for example when we went to Smith’s Lawn to watch dog cart races with Prince Philip.

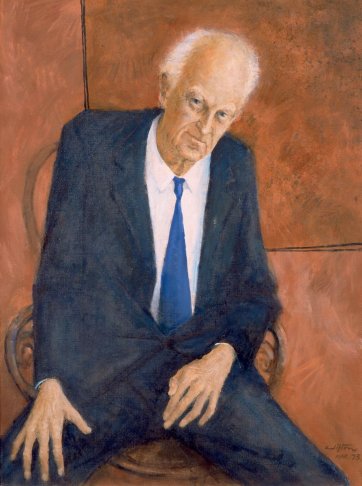

He worked across the whole board, beginning with broad gestures. These might change or be rubbed out, but large shapes and spaces began each work. As I write this I think “was it different when he painted, say, Lindesay Clark or Dick Hamer, with whom we had no prior relationship, from when he painted someone he knew well, such as David Williamson or Clyde Cameron?” But it was about expressing the character of the sitter, in society, and the picture in the context of art history; how to use this or that reference to emphasise personality, to play with colour or form. The process was the same.

I commented on Clif’s work only twice in twenty years. Clif was working on the 3’ x 4’ board we’d taken to (then Deputy Prime Minister) Sir John McEwen’s property. McEwen‘s history and stature simply didn’t fit on it. Although Sir John was in shirtsleeves, the painting was constrained and formal. Clif had an absolute view that only painters knew about painting, and I was content to be uninformed about it. But I kept seeing McEwen against the bare earth, in a suit: after all the Country Party saw itself locked in battle with an arid unrelenting land. I told Clif the board size was wrong, and the image. He was furious. In tears, I drove to a friend. He rang about an hour later. “You can come home, it’s ok.” In the studio was the finished painting, 6’ x 4’, McEwen suited against the blasted earth.

One has in front of one a subject. The word implies differential status, inter-dependency, the capacity on the one hand for objectivity, on the other, to tolerate examination. The situation is intimate; the outcome of the encounter is interpretive, material, public. While understood between us, these notions weren’t articulated. Clif talked about the need for clients to co-operate in the process of portraiture, but he was quite uninterested in a theoretical analysis of the power relationships involved in the studio.

He had won the Archibald with succeeding men of the moment. But by the mid 1970’s he too had become such a man. He’d intended portraiture to take off financial pressure, but events had brought their own. Forced on to the Australia Council to protect the arts policy developed by his committee, struggling with Coombs, whose ruthless manipulative character he had grasped in the 1963 portrait, he was increasingly distracted. He waited until the 1974 election was over, and resigned from the Council. We went to Bali for a holiday. There he had his first heart attack.

Artists brought paper, brushes, gouache to the Sydney hospital: he painted gifts of flowers and fruit, the view from the window. He was scared. But he would not change his behaviour, smoking and drinking hard. He had another heart attack. More flowers, more still lives of fruit. My father, a general practitioner, visited Clif in hospital after the third attack, and drew a diagram of the heart as a pump, so that Clif would know what was happening. And out poured paintings, drying on the floor so the nurses had to step carefully. The Artist as Patient, in striped pyjamas.

Margot Knox, also a painter and his old lover said to me “don’t listen to what he says, look at how he paints you.” In 1980, I joked that I wanted a Matisse like one we’d seen in Picasso’s collection at the Louvre, absolutely grey but alive with light. He made then a last portrait of me, in grey suffused with sadness. We knew that life together had become impossible.

Ten years later, in October 1990, I brought a friend to Dunmoochin. Clif was expansive, happy, showing us round, reminiscing. Clement Greenberg had stayed in 1979, carefully going through Clif’s work. In the punchy New York accent “I came out here in 1968 and I said then that your husband is the artist in Australia with the most potential. I say it again now. But sometimes, Judith, it’s your job to shoot him in the head when he’s half way through a painting”.

The words came back to me, as Clif showed Joe the portrait he was working on. He picked up the brush to gesture “I just have to do some more work on the hands.” To both our amazement, I took the brush and put it down. “No, Clif, look at it. It’s finished”. He stepped back beside me and looked. And took the brush and put it on the easel. “You’re right”, he said. We were both remembering the McEwen. “It’s finished”.

Judith Pugh