There is a little biographical information available for one of Dempsey’s match-sellers: a Liverpool character he identifies simply as ‘Billy the match man’.

A rare book of silhouettes in the Bodleian Library contains a collection of 43 character profiles, possibly after a number of different original hands. One of these — a one-armed Mancunian billposter — can be attributed to Dempsey on the basis of its signed original, while a number of the other, full-length figures in the collection are also closely reminiscent of his style. Of particular interest is the portrait of a ‘timber merchant’ taken in Liverpool.

It is common practice for beggars to avoid the necessity for verbal importuning by displaying a written sign indicating the nature of their affliction or the extent of their need. Paul Strand’s Blind woman (1917, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is a particularly memorable example of this kind of advertising, and the whimsically, ironically or topically reworded placard next to the donations hat became a favourite device of 20th century cartoonists. In 2005, Finnish artist Jani Leinonen presented an installation entitled I want to get rid of class distinction but all I think and do is a result of class distinction that consisted entirely of roughly scrawled placards he had purchased from beggars around the world.

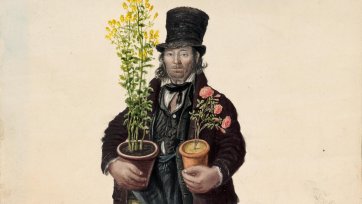

This auto-advertising was already a regular practice amongst the street people of Georgian and Regency Britain. One of the characters described in John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana is a charlatan — ‘a foreigner, and probably a Frenchman’ — who ‘throws up his eye-balls’ in pretence of blindness. Smith notes that this man ‘is now and then detected, in consequence of a picture, which is painted on a tin plate, and fastened to his breast, being the portrait of and worn many years ago by a marine, who had lost his sight at Gibraltar’. Likewise, in Dempsey’s watercolour of Billy we can see, hanging around the beggar’s neck, a placard on which is pasted a pair of silhouettes, with text beneath. Interestingly, these would appear to be copies of the print reproduced in the Bodleian book. It is possible that Dempsey’s 1844 portrait of this man is actually his second, and that Billy is wearing the first, drawn and printed some 15 years previously.

In the letterpress accompanying the earlier print, Billy is described as ‘a quiet inoffensive man’ who cries his wares in ‘a mild but effeminate voice’. Formerly a worker in a cotton mill, at the time of the portrait he had been in Liverpool for some 20 years. He claimed that the match business made him ‘a good putting on’, sufficient to support himself and his wife, though evidently not enough to provide him with a pair of shoes. The text also notes his stated intention to move from selling matches to selling rags although, from Dempsey’s later watercolour, it is clear that this modest ambition was not fulfilled. Still and forever the match man, Billy holds a bundle under his left arm, while with his right hand he proffers a bunch.

This late work in Dempsey’s series is one of his finest and most unsettling. Billy’s pathetic self-advertisement, his split and tattered coat and the blank stone wall behind him, testify eloquently to the match-seller’s marginal status. But here there is something stronger than objective description: in his resigned, affectless but direct stare, and in the way he thrusts the foreshortened sticks forward out of the picture plane and into the space of the viewer, Billy the Match Man boldly commands the attention and sympathy of commerce and charity.

Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, presented by C. Docker, 1956

Dempsey’s people: a folio of British street portraits 1824–1844 is the first exhibition to showcase the compelling watercolour images of English street people made by the itinerant English painter John Dempsey throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!