- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

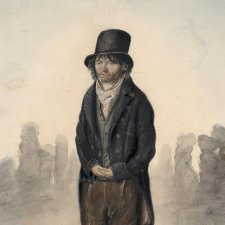

The appearance of vendors of ornamental plants ‘all a-blooming, all a-blowing’ in cries collections from the late 1790s onwards1 indicates the burgeoning enthusiasm of urban Britons for domestic gardening. Inspired by the botanical discoveries of 18th century exploration and scientific classification, and informed by the writings of picturesque and gardenesque theorists such as Humphry Repton and Uvedale Price, the English vogue for the suburban garden is also signalled by the establishment of the Royal Horticultural Society in 1804, and by publications such as John Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of gardening (1822), William Cobbett’s The English garden (1829) and the popular journal The Gardener’s Magazine (1826–44).

Nothing has been discovered about the Norfolk gardener Mr Copeman, but he is occupationally identifiable by his blue apron and by the potted roses and mustard flowers he carries in his huge hands, as well as by the curving beds at his feet in which more roses, as well as tulips and pansies, grow in stylised, china-decoration array. Copeman may have been an outdoor servant on a gentleman’s estate, or possibly an employee of the Royal Nursery, a commercial horticultural enterprise established at Yarmouth by Edward Youell.

Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, presented by C. Docker, 1956

31 July 2017

It may seem an odd thing to do at one’s leisure on a beautiful tropical island, but I spent much of my midwinter break a few weeks ago re-reading Bleak House.

Dempsey’s People curator David Hansen chronicles a research tale replete with serendipity, adventure and Tasmanian tigers.

30 June 2017

Those of you who are active in social media circles may be aware that through the past week I have unleashed a blitz on Facebook and Instagram in connection with our new winter exhibition Dempsey’s People: A Folio of British Street Portraits, 1824−1844.